Giant Sequoia Management Strategies on the Tule River Indian Reservation 1

advertisement

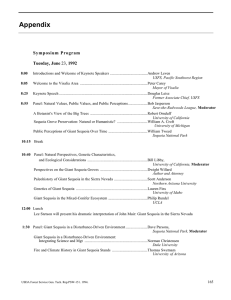

Giant Sequoia Management Strategies on the Tule River Indian Reservation1 Brian Rueger2 Abstract: Giant sequoia trees and forests have long been valued by members of the Tule River Tribal community. Management of the Reservation forests emphasize the enhancement of overall forest health and productivity while maintaining cultural and esthetic values. Strategies for managing giant sequoia forests have been developed and are implemented on a site specific basis. Projects are initiated and completed by the Tribe's Natural Resources Department. Located in southern Tulare County, California, the Tule River Indian Reservation was established in 1873. The Tule River Tribe is a federally recognized Indian Tribe governed by a nine-member Tribal Council. The tribe's land base encompasses nearly 55,000 acres. Giant Sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum [Lindl.] Buchholz) occurs with other conifer species at almost 5,500 to 6,000 feet elevation. The Tule River Tribal Council manages their sequoia groves with general oversight provided by the USDI Bureau of Indian Affairs. For over 40 years, Tribal use of the groves has focused on recreation, whitewood timber production, and utilization of dead and down wood for minor forest products. Current grove management strategies emphasize protecting the old-growth sequoias and selected young-growth replacements, maintain esthetic and cultural values, reducing fuel loads, improving sequoia regeneration, and integrating young-growth sequoia as a mixed-conifer timber component. The Reservation is characterized by a variety of landforms and vegetation types. Grassland, blue oak woodland and chaparral occupy the foothills below 4,000 feet. Black woodland and ponderosa pine forest dominate the 4,000 to 5,000 foot level. Mixed-conifer forest begins at about 5,000 feet and extends upwards to 7,000 feet. True fir forest can be found on north-facing slopes above 7,000 feet. Giant sequoia commonly mixes with ponderosa and sugar pine, white fir and incense-cedar between 5,500 and 6,500 feet. This diversity of forest and range resources has provided the Reservation community with recreational opportunities, cultural values, and economic benefits for many years. Forest management activities are planned in response to Tribal Council objectives and policy. Individual projects are implemented by the Tribe's Natural Resources Department with assistance from its forestry consultant, Integrated Forest Management. General oversight and assistance is provided by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. 1 An abbreviated version of this paper was presented at the Symposium on Giant Sequoias: Their Place in the Ecosystem and Society, June 23-25, 1992, Visalia, California 2 Consulting Forester, Integrated Forest Management, P.O. Box 711, Springville, CA 93265 116 Giant sequoia is found in relatively open stands and is the dominant species whenever it occurs in the mixed-conifer forest. These sites are among the highest, in terms of their productivity and potential for conifer growth, of any found on the Reservation. Subsequently, these locales were among the first to be entered when whitewood timber harvesting began more than 40 years ago. Except for the dead and down trees, the giant sequoias have not been used for forest products. Community use of giant sequoia areas has historically been for recreation, cultural values, and for products derived from the dead and down trees. These same areas comprise a high percentage of the best growing sites for the other mixed-conifer species and generate a significant portion of the whitewood timber sale revenue for the Tribal Council. Giant sequoia management strategies, therefore, involve providing both cultural and economic benefits to the Reservation community. ‘Micro’ Forest Management Although it is not Tribal custom to name and delineate ‘grove’ boundaries, the forest is broken into smaller aggregates, or ‘micro’ forests, each sharing one or several common characteristics. For example, a 300-acre giant sequoia forest may be further divided into smaller forests of similar species composition, density, age class or a combination of these and other characteristics. These aggregates are then mapped and the data entered into a geographic information system (GIS) database and combined with other resource information, such as cultural resources sites, soils, and fuel loads, for developing management strategies on a site specific basis. Generally, giant sequoia management strategies include: •Protecting the ancient giant sequoias and selected young ‘replacement’ trees •Maintaining esthetic and cultural values, particularly at those sites identified by the Tribal Council •Continuing to manage whitewood species for timber production, with emphasis placed on removing dead, dying, and hazardous whitewoods •Creating conditions favorable for giant sequoia estab- lishment and growth •Reducing fuel loads within and adjacent to giant sequoia management units •Integrating young-growth giant sequoia as a mixed- conifer timber component. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep.PSW-151. 1994 Observations following whitewood timber harvests in the 1950's and 1960's and more recent trials suggest that natural giant sequoia regeneration is best, and in many cases prolific, where openings larger than 1/2 acre were created and the surface of the ground was sufficiently disturbed to expose mineral soil for seedling establishment. If giant sequoia regeneration is a priority when planning a whitewood timber sale, the group selection or similar site specific silvicultural method is often applied. When a light whitewood harvest has occurred, an understory of white fir and incense-cedar usually follows with little or no sequoia establishment. Such silvicultural methods as individual tree selection, intermediate thinning, and sanitation cuts on the associated whitewoods may promote growth on younger sequoias and reduce fuel loads, but do little to enhance sequoia establishment. The Tribal Council is now concerned with the widespread mortality of whitewood species due to forest insect infestation. The resultant build-up of hazardous aerial fuels presents a significant fire hazard to the entire Reservation forest. Timber sales are currently geared towards removing dead, dying, and insect-infested whitewoods both within and outside giant sequoia sites. Where giant sequoia has naturally regenerated it usually outgrows the other mixed-conifer species. Since these areas are good growing sites they often support an overabundance of young trees of all species. Overstocked 15-30 year old stands are identified and considered for pre-commercial thinning through the Tribe's forest improvement program. Improving the mix of species and conditions for growth are important goals of the pre-commercial thinning program. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep.PSW-151. 1994. Giant sequoia is planted periodically with other conifer seedlings. Successful plantings have been made outside existing sequoia growing sites. Seedlings are purchased from the California Department of Forestry nursery system. We hope to begin collecting sequoia cones to eventually build a Reservation seed bank. Site preparation and ground fuel reduction is generally accomplished by using mechanical and manual methods. The Tribe can complete many of these tasks through timber sale proceeds or contracts. Prescribed burning has been used sparingly to date, primarily because of the narrow burning window, high cost, and risk. Burning is being given greater consideration, although it may have limitations when managing for all-aged stands. Conclusion Our goal in managing the giant sequoia, as with each of the conifer species, is to maintain a healthy mix of all ages and sizes. The forest and Reservation community is best served when a diverse selection of vigorous trees is supported. We have found that recreational opportunities for the Reservation Community can be enhanced, cultural and esthetic values of the forest maintained, and the Tribe's financial security met through prudent forest management strategies can enhance the health and vigor of the Tribe's giant sequoia, as well as their mixed-conifer forest. Although these objectives are inherently quite different, we have found they are not mutually exclusive. 117