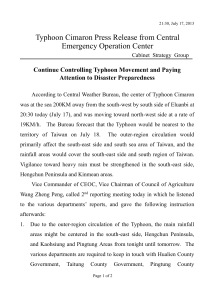

Printed for the Cabinet. February 1964 6th February, 1964 37

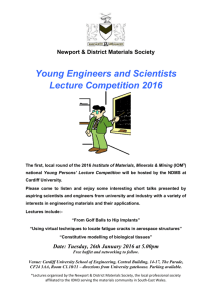

advertisement