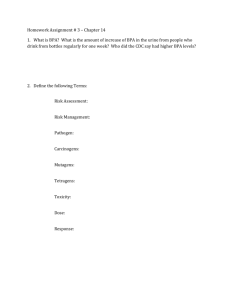

By L. INDUSTRIAL CHEMICALS AND THEIR KEEPERS:

advertisement