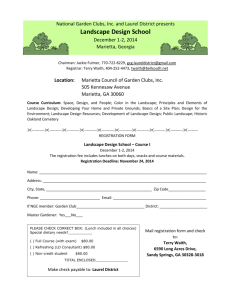

Georgia Landscape 35th Anniversary 2014

advertisement