Mapping hard and soft impervious cover in the Lake Tahoe Basin using LiDAR and multispectral images: a pilot study of the

Mapping hard and soft impervious cover in the Lake Tahoe Basin using LiDAR and multispectral images: a pilot study of the

Lake Tahoe Land Cover and Disturbance

Monitoring Plan

Prepared

For:

Pacific Southwest Research Station

Attn: Tiff van Huysen

Ecologist & Tahoe Science Program Coordinator

TCES Suite, 320

291 Country Club Drive

Incline Village, NV, 89451

Prepared

by:

Jarlath O’Neil ‐ Dunne , Dr.

David Saah, Tadashi Moody, Travis Freed, Dr.

Qi

Chen, and Jason Moghaddas on behalf of:

Spatial Informatics Group, LLC

3248 Northampton Ct.

Pleasanton, CA 94588 USA

Email: dsaah@sig ‐ gis.com

Phone: (510) 427 ‐ 3571

Report Date: March 18th, 2014

Page 1 of 29

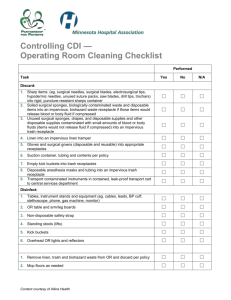

Contents

Abstract .........................................................................................................................................................

3

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................

3

Research Objectives ..............................................................................................................................

4

Methods ........................................................................................................................................................

5

Study Area .................................................................................................................................................

5

Data ...........................................................................................................................................................

5

Classification Scheme ................................................................................................................................

6

Feature Extraction .....................................................................................................................................

7

Results .....................................................................................................................................................

10

Accuracy Assessment ..............................................................................................................................

10

Land Cover Products Derived from LiDAR Data ..........................................................................................

12

Land Cover Products ...............................................................................................................................

12

Hydrography Polygons ........................................................................................................................

12

Transportation Linear Network ..........................................................................................................

12

Building Polygons ................................................................................................................................

13

Impervious Surfaces ............................................................................................................................

14

Accuracy ..................................................................................................................................................

15

Distribution .............................................................................................................................................

16

Broad Scale Summaries of Impervious Surfaces .........................................................................................

18

Statistical Summaries ..............................................................................................................................

18

Tahoe Basin (TRPA Boundary) .............................................................................................................

18

Parcels .................................................................................................................................................

19

Watersheds .........................................................................................................................................

23

Current LiDAR Derived Impervious Surface Coverage by Land Capability Class .................................

24

Discussion ...................................................................................................................................................

26

Acknowledgements .....................................................................................................................................

26

Literature Cited ...........................................................................................................................................

27

Non ‐ Discrimination Statement ...................................................................................................................

29

Page 2 of 29

Abstract

Conversion of land to impervious cover threatens the environmental quality of the Lake Tahoe Basin

(LTB) (Bailey 1974) by reducing water percolation into the soil and increasing runoff, and thus sediment, nutrient, and pollutant transfer into Lake Tahoe (Arnold and Gibbons 1996).

If impervious cover, both hard (e.g.

paved or roofed areas) and soft (e.g.

disturbed or compacted soil) expands to unsustainable or irreversible levels, many if not all of the environmental goals or “thresholds” central to management efforts within the Basin could be adversely affected.

Therefore, effective management and monitoring of impervious surfaces within the LTB requires an impervious cover data set that is detailed, accurate, and meaningful.

Spatial Informatics Group (SIG) mapped both hard and soft impervious surfaces in the

LTB by leverage existing investments in high ‐ resolution multispectral imagery, Light Detection and

Ranging (LiDAR), and vector GIS data.

This was accomplished through a repeatable and cost ‐ effective analytical methodology, centered on Object ‐ Based Image Analysis (OBIA) techniques (e.g.

O’Neil ‐ Dunne et al.

2012).

The end product consists of a spatially detailed, accurate, attribute ‐ rich, and realistic map of impervious cover within the LTB based on August 2010 ground conditions.

Impervious surface information was summarized by varying geographic units of analysis, including ownership (e.g.

parcels), environmental gradients/boundaries (e.g.

watershed, soil type, soil capability class) and political boundaries (e.g.

counties).

Finally, a pilot implementation of the Lake Tahoe Land Cover and

Disturbance Monitoring Plan (SIG 2009) was carried out using the derived impervious surface cover.

This analysis indicated that Land Capability Types 1b and 2 exceeded allowable coverage prescribed by Bailey

(1974) to maintain the “environmental balance” for combined, LiDAR derived hard and soft impervious cover types, which was consistent with the 2011 Threshold Report.

Utilizing this approach to monitoring impervious surfaces may provide a repeatable, cost effective approach to detecting watershed and LTB wide changes in impervious coverages in the future.

Introduction

Land conversion to impervious cover can accelerate sediment and nutrient deposition by “short ‐ circuiting” the hydrological cycle and increasing soil erosion (TRPA 2001 as cited in TRPA 2007).

Other indicators of ecosystem health including pollutant transfer, flooding intensity, stream flow, stream temperature and habitat loss are influenced by the amount of impervious cover (Arnold and Gibbins

1996, Tilley and Slonecker 2007).

If impervious cover exists or expands to excessive or irreversible levels it can affect all of TRPA’s nine threshold categories or areas of concern for the Tahoe Basin (e.g.

wildlife, fisheries, water quality, vegetation, etc.) (Minor and Cablk 2004).

To control for this, the Tahoe Regional

Planning Agency (TRPA) has placed limitations on land conversion (e.g., development) and disturbance

(e.g.

grading) within the Lake Tahoe Basin (LTB) based on amounts that are considered allowable to meet the soil conservation threshold standards (TRPA 2012).

TRPA’s impervious coverage standard, adopted in 1982 is based on the Bailey Land Capability

Classification System (Bailey 1974).

The Bailey classification consists of seven “land capability

Page 3 of 29

class/district” ranks, which are principally based on geomorphic conditions and soil type (Bailey, 1974).

Each one of the seven ranks has an associated allowable base coverage of impervious surfaces.

Increased deposition of fine sediment and nutrients are key factors reducing water clarity in Lake Tahoe

(Swift et al.

2006).

Up ‐ to ‐ date assessments of impervious cover in LTB are required to determine if threshold standard – acres and percent of impervious coverage (hard and soft), by land capability class are in attainment, to inform management decisions at the parcel and watershed scale and to serve as a baseline for future comparative analyses (SNPLMA 2010).

These needs are further outlined in the proposed “Lake Tahoe Land Cover and Disturbance Monitoring Plan” (SIG 2009).

Impervious cover is composed of hard, soft, and natural features.

Hard cover refers to land that is covered by materials such as buildings, pavement, exposed rock and concrete, and soft cover refers to disturbed and/or degraded soil (Cablk and Perlow, 2004) and as defined in the TRPA Regional Plan ‐

Code of Ordinances (2012).

Detecting, mapping, and identifying each subtype of impervious cover and its connectivity is important for evaluating impacts of impervious cover to environmental goals and developing appropriate management strategies.

There is thus a need to develop a cost ‐ effective and consistent approach for long ‐ term impervious surface monitoring that leverages passive and active remotely ‐ sensed data to differentiate between impervious surface types.

This project had four primary research goals and three research objectives, all of which were achieved.

The goals and objectives were to:

1.

Develop a cost ‐ effective and repeatable approach suitable for the long ‐ term monitoring of impervious surfaces within the LTB that leverages existing investments in remotely sensed imagery,

LiDAR, and vector GIS datasets.

2.

Generate products that provide decision makers and land managers with meaningful information about impervious surfaces at a variety of scales.

3.

Produce a GIS dataset that is an accurate and realistic representation of impervious surfaces within the LTB such that it is suitable for Effective Impervious Area (EIA) hydrologic modeling (e.g.

Subtheme 2b) and believable when viewed by the general public.

4.

Use this dataset to pilot implement the Lake Tahoe Land Cover and Disturbance Monitoring Plan

(SIG 2009).

Research Objectives

1.

Map hard and soft impervious surfaces within the LTB such that the user’s and producer’s accuracies for both types exceed 95% for the entire study area.

2.

Quantify the amount and extent of the various impervious cover types in the LTB by ownership, political, and environmental boundaries.

Page 4 of 29

3.

Use this dataset to pilot implement the proposed Lake Tahoe Land Cover and Disturbance

Monitoring Plan (SIG 2009).

Methods

Study Area

The study area consisted of the Lake Tahoe drainage basin plus Tahoe Regional Planning Agency (TRPA) jurisdictional boundary that includes some of the drainage area associated with the Truckee River outfall.

Impervious surface mapping was carried out for the entirety of the study area ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Impervious mapping study area.

Data

Source data for the impervious mapping consisted of a combination of remotely sensed and GIS vector data ( Table 1 ).

Page 5 of 29

Table 1.

Source datasets for impervious surface mapping.

Dataset

WorldView ‐ 2 pan ‐ sharpened 8 ‐ band multispectral imagery

LiDAR Normalized Digital Surface Model (nDSM)

LiDAR Digital Elevation Model (DEM)

LiDAR Normalized Digital Terrain Model (nDTM)

LiDAR Intensity

Property Parcels

Road centerlines

Trails

Hydrology polygons

Format

Raster

Raster

Raster

Raster

Raster

Vector

Vector

Vector

Vector

2010

Year

2010

2010

2010

2010

2009

Unknown

2009

2008

Horizontal

Resolution

0.46m

0.5m

0.5m

0.5m

0.5m

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

Classification Scheme

The impervious surface classification is depicted in Figure 2 .

The classification scheme consisted of hard and soft surface types and building, road, trail, and other (driveways, parking lots) feature types.

Figure 2.

Impervious surface classification scheme.

Photo ‐ interpretation keys were constructed by visiting representative areas for all the feature and

surface types listed in Figure 2 on the ground where one or more photographs were collected along with

Page 6 of 29

GPS coordinates.

Keys were also developed for features that could be easily misclassified as impervious

(e.g.

exposed rock).

The point locations and associated ground photographs were stored in KML file

( Figure 3 ).

Figure 3.

Example photo interpretation key for exposed rock, a feature type that could be confused with hard impervious surfaces.

Feature Extraction

The overall approach to feature extraction consisted of both automated and manual processes.

The automated mapping centered on an Object ‐ Based Image Analysis (OBIA) system developed using eCognition® version 8.7.

The design, development, and deployment of the OBIA system followed O’Neil ‐

Dunne et al.

(2012).

Manual editing of data was carried out using ArcGIS® 10.0.

The feature extraction cycle went through four stages ( Figure 4 ): 1) hydrology polygons, 2) linear transportation network, 3) building polygons, and finally 4) the comprehensive impervious surface dataset.

This incremental approach was designed to eliminate false positives by extracting non ‐ impervious features (e.g.

water) while at the same time iteratively increasing the amount of contextual information available for the classification algorithms (e.g.

distance to roads).

Each one of the stages resulted in a distinct product that was fed into the next stage, cumulating with the impervious surface classification.

Page 7 of 29

Figure 4.

Feature extraction stages.

Figure 5 depicts the cyclical nature of the workflow for each one of the four stages.

During each stage 1) the data were processed into data stacks and loaded into the OBIA system, 2) features were extracted

OBIA techniques, and 3) the quality of the data were improved using manual editing techniques.

Figure 5.

Impervious mapping workflow.

Page 8 of 29

Creating data stacks involved first dicing the data into tiles 3000x3000 pixels in size with 300 pixels of overlap.

The diced data were then loaded into the OBIA system via a customized import routine implemented in XML.

Each data stacked contained the imagery, LiDAR, and vector datasets ( Figure 6 ).

Following each stage the data stack was updated with the new/improved data.

Figure 6.

OBIA data stacks.

Page 9 of 29

Automated feature extraction was performed using a rule ‐ based expert system developed using the Cognition Network Language (CNL).

Figure 7 shows an example of the CNL rule set used in the final impervious classification.

The CNL rule set integrated image processing, surface calculations, segmentation, classification, fusion, and morphology algorithms into a single process.

Separate rule sets were developed for each of the four mapping iterations (Figure 4) and an example rule set is shown in Figure 7.

For a given iteration, a single rule set was applied to all data stack tiles.

Rule sets were developed based on the reference areas in the photo interpretation keys then applied to other areas and refined as necessary.

Post ‐ processing consisted of assembling the output tiles into a single basin ‐ wide mosaic.

Manual corrections were carried out via heads ‐ up digitizing techniques using the LiDAR and WorldView ‐ 2 imagery as the source data.

Review of the data occurred at a scale of 1:2,000.

Figure 7.

An example CNL rule set for impervious surface feature extraction.

Results

Accuracy Assessment

The accuracy assessment was carried out following Congalton and Green (2009).

A stratified sampling approach was employed in which 500 points were randomly placed on areas assigned to one of the impervious surface classes and 500 points were placed on areas not classified as impervious surfaces.

This stratified approach was designed to quantify errors of omission (the lack of inclusion of an impervious surface when it in fact existed on the landscape) and commission (the inclusion of impervious surface when it did not exist on the landscape).

Each point was independently assigned to one of the impervious surface classes ( Figure 2 ) by two technicians using the 2010 WorldView ‐ 2 imagery and LiDAR as the reference data ( Figure 8 ).

In the cases where the two technicians differentially defined

Page 10 of 29

the point, the point was revaluated and a consensus reached.

Producer’s, user’s, and overall accuracy were computed for both the impervious feature types and the impervious surface types.

Figure 8.

Accuracy assessment reference points.

Page 11 of 29

Land Cover Products Derived from LiDAR Data

Land Cover Products

Hydrography Polygons

The hydrography polygons generated as part of this project represent a marked improvement over the existing National Hydrography Dataset (NHD) polygons ( Figure 9 ).

The precision of the water ‐ land interface was refined, false water features were removed, and previously unmapped features were added.

Figure 9.

Hydrography polygons generated to support the impervious mapping (blue) compared to those from the National Hydrography Dataset (red) for Susie Lake.

Transportation Linear Network

The transportation linear network generated as part of the project represent a substantial upgrade of road and trail network both in terms of feature types, accuracy and precision (Figure 10).

This updated

Page 12 of 29

dataset, with some modifications to its topology, could be used for transportation modeling and analysis.

Figure 10.

Transportation linear network.

Building Polygons

The building polygon dataset represents the first comprehensive inventory of buildings for the Tahoe

Basin.

Use of the LiDAR enabled buildings to be extracted even if portions of the buildings were under tree canopy ( Figure 11 ).

The building data will support many uses ranging from attributing property parcels with building area information to identifying structures that have an elevation fire risk.

Page 13 of 29

Figure 11.

Building polygons (black lines) overlaid on the LiDAR Normalized Digital Surface Model (nDSM).

Impervious Surfaces

The objective of mapping both hard and soft impervious surfaces was achieved.

The ability to distinguish between various surface types and feature types will enable TRPA to use this dataset for a broad range of management and regulatory purposes, to include implementing the monitoring plan and applying the Bailey Land Capability Classification System (Figure 12).

Page 14 of 29

Figure 12.

Final impervious surface dataset depicting both the feature type and surface type.

Accuracy

The overall accuracy of mapped hard and soft impervious types was 94% ( Table 2 ).

Not surprisingly, the user’s accuracy of hard impervious surfaces was better than that of soft impervious surfaces as soft impervious surfaces were confused with non ‐ impervious features on the landscape that were also void of vegetation (e.g.

bare soil and exposed rock).

The overall accuracy of mapped impervious feature types was 90% ( Table 3 ).

The user’s accuracy of buildings, roads, and other (driveways/parking lots) features all exceeded 90%, but the user’s accuracy of trails was only 59%.

This can be attributed to the narrow configuration of trails in combination with the fact that they are often obscured by overhead canopy.

It is important to note that the estimates of accuracy presented in this report are for the entirety of the

Tahoe Basin.

It was not feasible to conduct assess the accuracy at multiple units of analysis (e.g.

parcels

Page 15 of 29

and watershed) for this project.

As such, these tables should not be used to draw conclusions on the accuracy for individual watersheds or parcels.

Table 2.

Impervious surface type error matrix.

Not

Not

472

Hard

6

Reference Data

Soft Total Producer's Accuracy

6 484 98%

Hard 7 362 5 374 97%

Soft

Total

User's Accuracy

25

504

94%

15

383

95%

102 142

113 1000

90%

72%

94%

Table 3.

Impervious feature type error matrix.

Not

Road

Trail

Building

Other

Total

User's Accuracy

Not

473

7

29

1

23

533

89%

Road

Reference Data

Trail Building Other Total

2

168

1

1

8

180

93%

5

2

20

0

7

34

59%

1

2

0

100

2

105

95%

2

6

2

4

134

148

91%

483

185

52

106

174

1000

Producer's Accuracy

98%

91%

56%

94%

77%

90%

Distribution

A hot spot analysis was carried out to highlight concentrations of impervious surfaces within the Tahoe

Basin.

Impervious surface percentages were summarized to 100m grid cells then the Getis ‐ Ord Gi* statistic (ESRI 2013) was computed using ArcGIS.

The Gi* statistic is a Z score.

“For statistically significant positive Z Scores, the larger the Z score is, the more intense the clustering of high values.

For statistically significant negative Z scores, the smaller the Z Score is, the more intense the clustering of low values” (ESRI 2013).

Not surprisingly, hard impervious surfaces are concentrated in the more urbanized portions of the Lake

Tahoe Basin close to the lake ( Figure 13 ).

Page 16 of 29

Figure 13.

Hard impervious surface hot spot analysis based on average percent impervious in 100m grid cells.

Higher GiZ scores are indicative of clusters (“Hot Spots”) of hard impervious surfaces.

Cluster analysis is similar to, but not the same as a density analysis.

Page 17 of 29

Broad Scale Summaries of Impervious Surfaces

Statistical Summaries

Impervious surface metrics were computed for the following geographic boundaries:

1.

The Lake Tahoe Basin (watershed plus other administrative boundaries)

2.

Property parcels a.

Property boundaries b.

Ownership c.

Parcel land use classes

3.

Census block groups

4.

Watersheds a.

Primary b.

Sub basins 184

For each geography unit of analysis the area of each impervious feature type and surface type was summarized along with the percent of land covered by each impervious feature type and surface type.

Tahoe Basin (TRPA Boundary)

Overall (including area associated with water bodies), 1.9% of the Tahoe Basin is covered by hard impervious surfaces, totaling 6,175 acres and 0.5% of the Tahoe Basin is covered by soft impervious surfaces, totaling 1,810 acres, totaling approximately 7,942 aces.

This estimated total impervious coverage acreage represents about 3.95% of the land area in the LTB (study area boundaries).

In terms of impervious surface types the largest single type of impervious surface are roads, followed by other

(driveway/parking lots), buildings, and trails.

Page 18 of 29

Figure 14.

Impervious surface type and feature type summaries for the Tahoe Basin based on the TRPA boundary.

Parcels

Impervious surface metrics were computed for all 62,962 parcels within the TRPA boundary.

An example of per ‐ parcel hard impervious is shown in ( Figure 15 ).

Page 19 of 29

Figure 15.

Per ‐ parcel hard impervious metrics.

The majority of parcels (65%) have 20% or less of their land area covered by impervious surfaces ( Figure

16 ).

Page 20 of 29

Figure 16.

Distribution of parcels by % impervious.

An analysis of parcel ownership categories shows that the majority of impervious surfaces are on private property ( Figure 17 ).

When the ownership patterns are broken down by surface types most of the hard impervious surfaces are on private land, but most of the soft impervious is on land owned by the Forest

Service.

Page 21 of 29

Figure 17.

Impervious surfaces by ownership type.

The size of the circles in the bubble chart corresponds to the area of hard impervious and the color gradient (bottom of graphic) the area of soft impervious.

Note than roads do not have an ownership type and thus are exclude from this analysis.

In terms of land use the vast majority of hard impervious surfaces are in the rights ‐ of ‐ way (ROW) and on single ‐ family dwellings ( Figure 18 ).

Impervious surfaces in the ROW are primarily roads, whereas impervious surfaces in single ‐ family dwellings are a combination of buildings and driveways.

Page 22 of 29

Figure 18.

Impervious surface metrics broken out by land use.

The size of the box represents hard impervious acres by land use, the color represents the area of soft impervious per land use class.

Watersheds

Impervious metrics were generated for both the primary sub ‐ watersheds and the 184 sub ‐ basins.

Sub ‐ watersheds in the urbanized areas near the lake have the highest percentage of their land area covered by hard impervious surfaces ( Figure 19 ).

Page 23 of 29

Figure 19.

Percent of land in each primary sub ‐ watersheds covered by hard impervious surfaces.

The white polygon in the northwest of the Basin has precisely 0% impervious surfaces.

Current LiDAR Derived Impervious Surface Coverage by Land Capability Class

The LiDAR derived soft and hard impervious cover map derived by Spatial Informatics Group (SIG) was utilized to estimate impervious land coverage by Land Capability Class (Bailey 1974) (Table 4).

Only two

Land Use Capability types, 1b and 2, exceeded the Bailey (1974) coverage for combined totals of both soft and impervious coverage.

Within Land Capability Type 1b, the coverage was exceeded by 668 acres or 5.9% above the total acreage recommended in Bailey 1974.

Within Land Capability Type 2, coverage was exceeded by 42.9

acres or 0.2%.

These findings are consistent with key findings reported in the

2011 Threshold Report, who also noted Land Capability Classes 1b and 2 “…to be exceeding allowable coverage targets by 670 and 43 acres..

“ (Choy et al.

2011).

Page 24 of 29

Table 4.

Hard, soft, and total impervious coverage for the Lake Tahoe Basin in 2010 by Bailey (1974) Land Capability Class.

Current impervious coverages are compared with Bailey (1974) allowable coverages, with acres and percent over or below these thresholds reported on the far right columns of Figure 20.

Land

Capability

Class

Total

Area

1a

1b

1c

2

3

4

5

6

7

Grand

Total

Percent of LTB

Area

1

Acres (%)

23,477.0

12%

11,288.3

6%

53,578.0

27%

23,626.1

12%

16,786.2

8%

32,250.7

16%

10,294.9

5%

24,260.2

12%

5,513.5

3%

201,074.9

100%

Pervious Coverage

Acres (%)

23,302.7

99.3%

10,506.6

93.1%

53,077.3

99.1%

23,346.9

98.8%

16,434.0

97.9%

30,988.8

96.1%

9,199.0

89.4%

22,046.8

90.9%

4,230.4

76.7%

193,132.6

96.1%

Hard Impervious

Coverage

Acres (%)

75.7

0.3%

673.6

6.0%

261.5

0.5%

134.8

0.6%

184.3

1.1%

918.1

2.8%

912.2

8.9%

1,847.8

7.6%

1,160.5

21.0%

6,168.5

3.1%

Soft Impervious

Coverage

Total

Impervious

Coverage

Acres (%) Acres (%)

98.6

0.4%

108.1

1.0%

239.2

0.4%

174.3

781.7

500.7

0.7%

6.9%

0.9%

144.4

0.6%

167.9

1.0%

343.8

1.1%

183.7

1.8%

365.5

1.5%

122.6

2.2%

1,773.8

0.9%

279.2

352.2

1,261.9

1.2%

2.1%

3.9%

1,095.9

10.6%

2,213.3

9.1%

1,283.1

7,942.3

23.3%

3.9%

Bailey

Allowed

Coverage

Acres

234.8

112.9

535.8

(%)

1.0%

1.0%

19,915.0

9.9%

1.0%

236.3

839.3

1.0%

5.0%

6,450.1

20.0%

2,573.7

25.0%

7,278.1

30.0%

1,654.1

30.0%

Exceeding or (Below)

Bailey Allowable

Thresholds

Acres

(60.5)

668.8

(35.1)

(

(%)

‐

0.3%)

5.9%

( ‐ 0.1%)

42.9

(487.1)

0.2%

( ‐ 2.9%)

(5,188.2) ( ‐ 16.1%)

(1,477.8) ( ‐ 14.4%)

(5,064.7) ( ‐ 20.9%)

(370.9) ( ‐ 6.7%)

(11,972.7) ( ‐ 6.0%)

Page 25 of 29

Discussion

This project succeeded in mapping both hard and soft impervious surfaces in the Lake Tahoe Basin with a high degree of accuracy.

Crucial to the project’s success was the availability of high ‐ resolution, high ‐ quality remotely sensed data.

The combination of LiDAR and spectral imagery allowed for the differentiation of impervious surfaces based on both their structure and material.

By having impervious surface data summarized at multiple geographical units, managers have the information they need to identify and target specific areas from the watershed to the parcel, for the purposes of either removing impervious surfaces or disconnecting them from the hydrologic network.

Furthermore, this dataset served to identify land capability classes that are not incompliance with development standards.

The dataset produced as part of this study should serve as the foundation for future impervious surface mapping, lowering the cost of future mapping efforts and assisting mangers in understanding how impervious surfaces are changing in the Basin.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency and local land management experts for their assistance over the course of this project.

Funding for this project was provided by the Southern

Nevada Public Land Management Act (SNPLMA).

Page 26 of 29

Literature Cited

Alley, W.

M., and J.

E.

Veenhuis.

1983.

Effective impervious area in urban runoff modeling.

Journal of

Hydraulic Engineering 109(2): 313 ‐ 319.

Arnold, C.

L., and C.

J.

Gibbons.

1996.

Impervious surface coverage: the emergence of a key environmental indicator.

Journal of the American Planning Association 62(2): 243 ‐ 258.

Bailey, R.

G.

1974.

Land ‐ Capability Classification of the Lake Tahoe Basin, California ‐ Nevada: A Guide for

Planning .

South Lake Tahoe, CA: US Forest Service, US Department of Agriculture in cooperation with the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency.

Brabec, E., S.

Schulte, and P.

L.

Richards.

2002.

Impervious surfaces and water quality: a review of current literature and its implications for watershed planning.

Journal of Planning Literature

16(4): 499 ‐ 514.

Cablk, M.E., and L.E.

Perlow.

2006.

A classification system for impervious cover in the Lake Tahoe Basin .

Final Report.

Reno, NV: Nevada Water Resources Research Institute.

Choy, J., Romsos, S., Loftis, W., O’Neil ‐ Dunne, J., Nielson, P., Saah, D., and Oehrli.

2011.

Chapter 5, Soil

Conservation, In : 2011 Threshold Evaluation.

Tahoe Regional Planning Agency.

175p.

http://www.trpa.org/regional ‐ plan/threshold ‐ evaluation/

ESRI (Environmental Systems Research Institute) 2013.

How Hot Spot Analysis: Getis ‐ Ord Gi* (Spatial

Statistics)works.

Accessed from http://edndoc.esri.com/arcobjects/9.2/NET/shared/geoprocessing/spatial_statistics_tools/how

_hot_spot_analysis_colon_getis_ord_gi_star_spatial_statistics_works.htm

on 12/30/2013

Long, J.

2010.

Tahoe Science Update Report .

Incline Village, NV: US Department of Agriculture, US Forest

Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station.

Minor, T.B., and M.E.

Cablk.

2004.

Estimation of impervious cover in the Lake Tahoe Basin using remote sensing and geographic information systems data integration.

Journal of the Nevada Water

Resources Association 1(1): 58 ‐ 75.

O’Neil ‐ Dunne, Jarlath P.M., Sean W.

MacFaden, Anna R.

Royar, and Keith C.

Pelletier.

2012.

An Object ‐ based System for LiDAR Data Fusion and Feature Extraction.

Geocarto International (May 29): 1–

16.

doi:10.1080/10106049.2012.689015.

Spatial Informatics Group (SIG).

2009.

Lake Tahoe Land Cover and Disturbance Monitoring Plan .

Stateline, NV: Tahoe Regional Planning Agency.

Swift, T.

J., J.

Perez ‐ Losada, S.

G.

Schladow, J.

E.

Reuter, A.

D.

Jassby, and C.

R.

Goldman.

2006.

Water clarity modeling in Lake Tahoe: Linking suspended matter characteristics to Secchi depth.

Aquatic Sciences ‐ Research Across Boundaries 68(1): 1 ‐ 15.

Page 27 of 29

Tahoe Regional Planning Agency.

2001.

Regional plan for the Lake Tahoe Basin: 2001 Threshold evaluation draft.

Stateline, NV.

Tahoe Regional Planning Agency.

———.

2007.

Threshold Evaluation Report.

Stateline, NV.

Tahoe Regional Planning Agency.

Tetra Tech.

2007.

Watershed hydrologic modeling and sediment and nutrient loading estimation for the

Lake Tahoe total maximum daily load.

Lahontan Regional Water Quality Control Board.

http://www.waterboards.ca.gov/lahontan/water_issues/programs/tmdl/lake_tahoe/docs/peer

_review/tetra2007.pdf

Tilley, J.

S., E.

T.

Slonecker, 2006.

Quantifying the components of impervious surfaces .

U.S.

Geological

Survey.

Open ‐ File Report 2006 ‐ 1008.

USGS publications website.

http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2007/1008/ofr2007 ‐ 1008.pdf

.

Page 28 of 29

Non ‐ Discrimination Statement

“In accordance with Federal law and U.S.

Department of Agriculture policy, this institution is prohibited from discriminating on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age or disability.

(Not all prohibited

bases apply to all programs.)

To file a complaint of discrimination: write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326 ‐ W, Whitten

Building, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C.

20250 ‐ 9410 or call (202) 720 ‐ 5964 (voice and TDD).

USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer.”

Page 29 of 29