THE PATH OF PROTECTIon ImPROVIDG

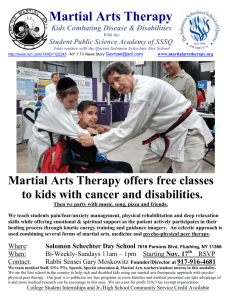

advertisement