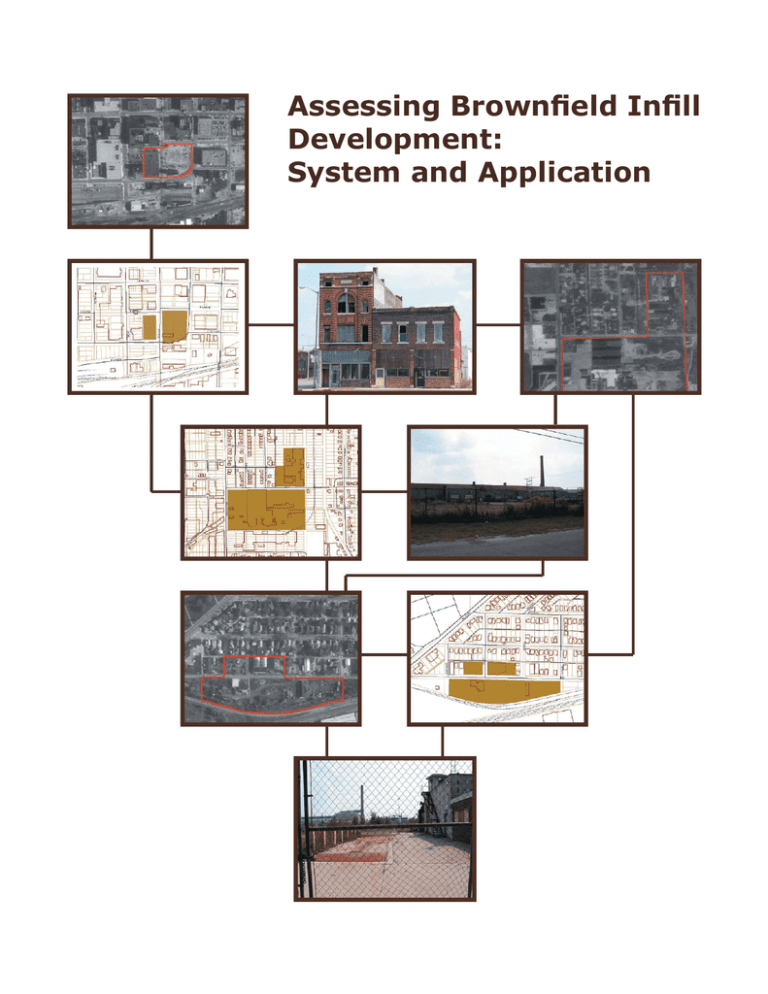

Assessing Brownfield Infill Development: System and Application

advertisement