Reading Problems, Attentional Deficits, and Current Mental Health Status

The Joumai of Correctional Education 58(3) • September 2007

Reading Problems, Attentional Deficits, and Current Mental Health Status in Adjudicated Adolescent Males

Natalie O'Brien

Jennifer Langhinrichsen-Rohling

John Shelley-Tremblay

Abstract

This study examined the prevaience of reading probiems and seif-reported symptoms

of attentionai deficits in a sample of adjudicated adoiescent maies (N = 101) aged 12 to

18 years who were residing in an aiternative sentencing residentiai program. Thirtyfour percent of the youth had reading probiems whiie oniy 9% of the boys had selfreported attentionai deficits. An additionai 10% of the youth reported experiencing both reading probiems and attentionai difficulties. Resuits indicated that maie offenders with attentionai deficits reported greater depression, reduced seif-concept, and a more external locus of control at intake than maie offenders with reading difficuities.

Furthermore, maie youth offenders with reading and attentionai probiems reported more depression, iess positive self-concepts and a more external iocus of control than did youth with reading problems oniy, but did not differ significantiy from the group who only reported attentionai problems. Overail, these findings exempiify the need for both educational and psychological interventions for youVi entering the juveniie justice system. Psychoiogicai interventions for maie offenders who self-report attentionai difficulties may be particuiariy wananted.

The Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquenq^ Prevention, in conjunction with the United States Department of Education, has recently stressed the necessity of addressing the needs of youth in the juvenile justice system who suffer with learning or mental health disabilities (National Council on Disability, 2003). it

This research was supported by Grant No. 2001 -SI-FX-0006, entitled USA Youth Violence Prevention Initiative, award by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Office of Justice Programs, U. S. Department of Justice. The second author Is currently appointed to the Youth Violence Scholar position at the University of

South Alabama.

293

The Joumai of Correctional Education 58(3)»September 2007

Reading Problems and Attentionai Deficits in Adolescent Males O'Brien, e t al has also been noted that the majority of existing research on disabilities in delinquent adolescents has been conducted in long term correctional facilities, so that much less is i<nown about learning disabled offenders or offenders with mental health diagnoses who are invoived in other parts of the juvenile justice system (i.e., probation, short-term detention, and residential placement).

Therefore, this current study focused on adjudicated youth who were residing in an aiternative sentencing residential faciiity. The prevalence of reading problems and self-reported attentionai deficits was determined, as was the reiationship between having a learning or attentionai problem and mental health status and perceived iocus of control at intake to the faciiity

Reading Problems

Among the various types of iearning disabilities, reading disabilities are of particuiar interest to study in juvenile correctional faciiities both because they are prevalent in samples of delinquent youth, and because delinquent youth with reading disabilities appear to have higher recidivism rates than their peers without reading disabilities (Archwarnety & Katsiyannia, 2000; Brunner, 1993).

Furthermore, remediating reading deficits among deiinquent youth has been shown to reduce the lii<eiihood that youth wiii recidivate (Brunner, 1993), estabiishing this as an important target for intervention while youth are involved in the juveniie justice system.

Currently, there is no one universaiiy agreed upon strategy to determine if an adoiescent has a reading disabiiity. However, a popuiar way to identify a reading disability is to estabiish that there is a significant discrepancy between an individuai s reading achievement and his or her estimated abiiity to read.

The hypotheticai reading estimate is typicaily based on a formuia which considers the youth s intelligence, education, and age (DSM-iV, APA, 1994). Yet, greater numbers of researchers have criticized the discrepancy criterion for a number of reasons, inciuding controversies over how to best measure inteiiigence and mounting evidence that poor phonoiogicai decoding si^iiis may be one of the i<ey component of reading difficuities, regardiess of inteiiigence or achievement (Stanovich & Siegei, 1994). These concerns have ied other researchers to suggest that the criteria for a reading probiem be made on the basis of an individual s number of years behind in reading compared to the expected reading ievei for his or her chronological age (Sattier,

2002).Consequently, in the current study, this method was utiiized to identify adjudicated youth with reading problems.

Regardless of choice of operationai definition or method of assessment,

294

The Journal of Correctional Education 58(3)»September 2007

O'Brien, et. al Reading Problems and Attentional Deficits in Adolescent Males reading difficulties have been siiown to be prevaient among juvenile offenders. For example, Finn, Stott, and Zarichny (1988) studied 104 delinquent youth and found that 43% were reading two or more years behind grade level. Likewise, Project

READ, a nationai project to improve reading skiils among deiinquent youth found that, on average, their juveniie offenders read on a fourth grade ievel, but their mean actuai grade level was ninth grade (as cited in Brunner, 1993).

However, some have suggested caution when interpreting resuits from these studies because most researchers studying reading disabilities in deiinquent youth have not measured for the potential co-occurrence of attentional probiems. Specificaiiy, a study conducted by iVIaguin, Loeber, and

Lemahieu (1993) determined that reading probiems did not have a unique relationship with deiinquency, instead, it was the interaction between deficits in attention and reading problems that was central. These authors strongly urged researchers to measure attentionai deficits, reading probiems, and deiinquency simultaneously. Consequently, we also chose to measure the occurrence of attentional deficits in adjudicated youth.

Problems with Attention

The diagnostic iabei most commoniy associated with attentional deficits is

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder or ADHD. Generally, the prevalence of

ADHD in US chiidren has been shown to range from 3% to 7% (DSiVl-IV-TR,

APA, 2000) but the rates of ADHD have been shown to vary substantiaiiy across particular schools, settings, and samples. For exampie, the rate of ADHD in delinquent sampies has been reported to be as high as 46% (Otto,

Greenstein, Johnson, & Friedman, 1992). in contrast, Moffitt and Siiva (1988) reported an ADHD rate of 278% among a sample of 13-year-old delinquent males, in 2005, Langhinrichsen-Rohiing et ai. obtained a seif-reported rate for

ADHD of 19.5% among a sampie of deiinquent male youth who were residing in an aitemative sentencing program. The rate obtained by Langhinrichsen-

Rohiing et ai. (2005) was also eievated in comparison to samples drawn from the generai community, however, their particuiariy iower estimate is consistent with the finding that asking youth to self-report symptoms of attentionai deficits and hyperactivity typlcaiiy ieads to an underestimated rate (e.g., Danckaerts,

1999; Smith, Peiham, Gnasy, iVIoiina, & Evans, 2000).

iVIoreover, as with reading disabilities, finding reiiabie methods to diagnose

ADHD has been proven to be compiex. Suggested state-of-the-art strategies inciude behaviorai observations of the youth in muitipie settings, use of reports from muitipie informants, inciuding subjective and objective data in the

295

The Joumai of Correctional Education 58(3) • September 2007

Reading Problems and Attentional Deficits in Adolescent Males O'Brien, e t al diagnostic process, compietion of paper and pencii and computer tasks, and even utiiizing brain imaging or electrophysioiogicai techniques (Root a Resnick,

2003). However, very few components of the juveniie justice system have iong enough contact with the youth or enough resources to conduct such a compiete evaiuation. Fortunately, some self-report measures of attentionai deficits exist. These measures have generaiiy been shown to have high interrater reiiabiiity and to be abie to predict generai outcomes vaiidiy

(Danckaerts, 1999), aithough they tend to err on the side of underdetecting attentionai deficits (Smith et ai., 2000). For feasibiiity, this methodology was chosen in the current study to identify youth with attentional deficits, rather than to determine if the youth met criteria for a formai diagnosis of ADHD.

Researchers have aiready estabiished that attentional problems and iearning disabiiities frequentiy co-occur in the same chiidren. For example, Barkiey

(1990) reported a co-occurrence rate between ADHD and learning disabilities ranging from 19% to 26% in schooi age children. Hinshaw (1992) reported that

10% to 20% of chiidren suffer with comorbid ADHD and learning disabiiities; whiie Pennington (1991) Indicated that the overlap between ADHD and reading disabiiities, in particuiar, was quite high, (i.e., between 9% and 33%).

To date, however, the co-occurrence of reading probiems and attentionai difficulties in delinquent or adjudicated youth has not been fuiiy determined. At a theoreticai ievei, substantiai overiap is expected as iVioffitt (1990) postuiated that there might be an underlying physioiogical pathology, perhaps residing in the centrai nervous system, that will be shown to account for the more frequent than would be expected reiationships among ADHD, deiinquency, and cognitive probiems such as reading difficuities. Based on iVioffitt's theory, it was hypothesized that a substantiai number of adjudicated youth in our study wouid exhibit both probiems with reading and attentionai deficits (RP and AD).

This group wouid then form an additionai comparison group to youth with only reading probiems (RP oniy) and to youth with oniy attentional deficits (AD only).

The remaining youth wouid be considered to have non-elevated levels of reading difficuities and attentional problems (No RP or AD)

A priori, we expected that deiinquent youth in these four groups would differ in their mentai health functioning as they entered an residential faciiity to compiete an aitemative sentencing agreement. Three aspects of mentai heaith functioning were chosen for consideration. They were: symptoms of depression, internal versus external locus of control, and current seif-concept. These three constructs were chosen for study because of previous research which has linked these constructs to reading probiems and/or attentionai difficuities and because

296

The Joumai of Correctional Education 58(3) • September 2007

O'Brien, e t al Reading Probiems and Attentional Deficits in Adolescent Males of their reievance to deiinquency-reiated programs conducted by staff at the juvenile justice facility. Specificaiiy, at the particular faciiity where this research occurred, there were on-going programs to promote a core sense of self and integrity in the youth (the iVIAGIC program), to internalize the youth's iocus of control (in order to combat peer pressure for deiinquency upon reiease), and to counteract the youth's feelings of negative seif-worth, depression, hopeiessness and/or heiplessness about their future (in order to motivate the youth to take advantage of this change opportunity and to encourage each boy to keep in school in order to compiete their education).

Some previous investigations have considered the reiationships among reading disabiiities, ADHD, and symptoms of depression. For example, Wiicutt and Pennington (2000) reported a significant reiationship between having a reading disabiiity and depression among boys, but indicated that the reiationship was mediated by ADHD. In contrast, in a iongitudinai study, iVIaughan, Rowe, Loeber, and Stouthamer-Lober (2003), found depression to be related to reading probiems in seven and ten year oid boys, independent of any disruptive behavior disorder (e.g., ADHD). However, they did not find a relationship between depression and reading probiems in teenage boys, so this relationship may be attenuated by age. Mayfieid Arnoid, Goidston, Waish, et ai.

(2005) studied the prevaience and severity of behaviorai and emotional probiems, inciuding depression, in a sampie of reading disordered adolescents.

They found that even after controiiing for the effects of ADHD and demographic differences, reading disabied participants reported greater ieveis of depression, somatic compiaints, and trait anxiety than normal controls, in generai, symptoms of depression have been shown to be prevalent and yet frequently overlooked in incarcerated boys (Teplin, 1990). Yet, depressive symptoms may be a risk factor both for difficuity completing the program and for engagement in seif-injurious behavior whiie incarcerated (Langhinrichsen-

Rohiing et ai., 2005). Comorbidity among psychiatric probiems has aiso been shown to occur at high rates amongst youth in the juveniie justice system

(Atkins et ai., 1999). However, few, if any previous studies have been conducted with deiinquent youth who were adjudicated to an aitemative sentencing residentiai setting. This indicates that continued study of the experience of depressive symptoms among adjudicated youth within the juvenile justice system with reading probiems only, attentionai deficits oniy, or both, is warranted.

Some previous studies have aiso considered how ieaming disabiiities and

ADHD may effect a youth's iocus of control. For example, Tarnowski and Nay

297

The Joumai of Correctional Education 58(3)»September 2007

Reading Problems and Attentional Deficits in Adolescent Males O'Brien, e t al

(1989) examined iocus of control in seven to nine year old boys in four groups:

Learning Disordered or LD, ADHD, LD/ADHD, and No LD/No ADHD. They found that the LD group and the comorbid LD/ADHD group reported the most externai iocus of controi. Thus, ADHD aione was not associated with an extemai locus of controi. However, other researchers have examined the relationship between ADHD and locus of controi, without inciuding LD as a variable, and found ADHD to be significantiy associated with a more external locus of controi. Specificaiiy, Lufi and Parish-Piass (1995) found that Israeli boys

(seven to thirteen years oid) with ADHD had a more externaiiy oriented iocus of controi than non-ADHD boys. Furthermore, Hoza, Waschbusch, Peiham, iVIoiina, and Miilch (2000) found that boys (seven to tweive years oid) with ADHD had a more externai iocus of controi regarding their sociai performance compared to non-ADHD boys. Another body of iiterature highiights that an internal iocus of controi, which is defined as people's tendency to beiieve that there own actions determine the rewards that they receive (Rotter, 1966), is an expiicit target of change for some juveniie justice programs and may provide youth with a deterant to recidivism (Langhinrichsen-Rohiing et ai., 2005). Thus, this is an important construct to inciude given the reiative iack of iiterature considering the reiations among attentionai probiems, reading difficuities and iocus of controi in youth invoived in the U.S. juvenile justice system.

Finaiiy, there are a number of studies which demonstrate that youth with reading disabiiities have different self-concepts than youth without these difficuities (e.g., Frederickson a Jacobs, 2001; Tabassam a Grainger, 2002).

Attentional probiems aiso have been repeatediy been shown to be associated with a more negative seif-concept and poorer peer reiationships, perhaps particuiariy for boys (e.g., Peiham a Bender, 1982; Hoza et al., 2005).

IVIoreover, youth with co-morbid reading and attentionai problems have been shown to have the greatest impairment in their academic seif-concepts and seifefficacy (Tabassam a Grainger, 2002). However, the nature of the associations among these constructs in adjudicated youth appears to be currentiy unknown and thus is additionai focus of the current study.

In summary, reiativeiy few existing studies have examined reading probiems, with or without symptoms of attentionai deficits in adjudicated youth who are residing within the juveniie justice system. Yet, in non-adjudicated samples, these deficits have been shown to reiate to three important juveniie justice program outcomes: depression ieveis, internai versus external iocus of controi, and seif-concept.

Therefore, the foiiowing hypotheses were generated: (1) Reading probiems

298

The Journai of Correctional Education 58(3)»September 2007

O'Brien, et. al Reading Problems and Attentionai Deficits in Adoiescent Males

(RP) and attentional difficulties (AD) wiii be prevaient in adjudicated youth. (2)

Male deiinquents witii either RP or AD will report more symptoms of depression, iess positive seif-concepts, and a more externai iocus of controi than wiil male deiinquents who do not have RP or AD. (3) Male adolescents with both RP and AD (the comorbid group) will report more symptoms of depression, iower seif-concepts, and a more externai iocus of control than either of the one-diagnosis groups (RP oniy or AD oniy) or the No RP or AD comparison group.

Method

Participants

Participants for this study consisted of 101 maie adjudicated youth who were sentenced to the CAMP Robert J. Martin Youth Leadership Academy, a shortterm residentiai miiitary style program located in rurai Aiabama. The CAMP

Martin program requires the youth to compiete thirteen 'successful" (infractionfree) weeks before they can be reieased from the program.

The participants for this study were recruited consecutiveiy over a one year period of time. Youth sentenced to this program have typically committed a number of offenses, some of which are serious, but they are not generaiiy considered to be vioient. For exampie, in a previous study conducted at this facility, Langhinrichsen-Rohiing et ai. (2005) reported,'... the average maie at this faciiity has approximateiy six previous offenses.... [and] the majority of these youth have committed crimes against property such as shopiifting, breai<ing and entering, and burglary/theft" (p.7).

In the current sample, the average age of the male juveniies was 15.5

years (range 12 to 18 years oid). Over haif of the participants, 53% (n = 53), were African American; 37% (n = 37) were Caucasian, 1 % (n = 1) was Hispanic,

2% (n = 2) were Asian American, 3% (n = 3) were Native American, and 4% (n

= 4) reported that they were some other race than those noted above.

Measures

Gates - MacGitiltie Reading Tests - Fourth Edition: The CM/?r (MacGinitie S

MacGinitie, 2000) is designed to measure the siient reading si<iils of chiidren in kindergarten through 12th grade. The test provides an assessment of reading skiiis in two domains (vocabuiary and comprehension). For the purpose of this study oniy the comprehension subtest was administered. Participants were given a maximum of thirty-five minutes to compiete the comprehension section on the Gates - MacGinitie Reading Tests. Youth were classified as having a

299

The Joumai of Correctionai Education 58(3) • September 2007

Reading Probiems and Attentional Deficits in Adoiescent Males O'Brien, e t ai reading probiem using a year's behind criteria (Sattier, 2002). Specificaiiy, a RP iabei was generated if the boy's reading achievement ievei was more than two year's behind his last grade placement in schooi, if he had completed 5th through 8th grade, or If his reading ievei was more than three years behind if he had compieted 9th through 12th grade.

Conners' - ADHD/DSM - IV Scales - Adoiescent (CADS-A): The CADS - A

(Conners, 2001) is a 30-item scale used to assess Attention Deficit Hyperactivity

Disorder. The CADS-A is a paper-and-pencil, self-report measure requiring respondents to indicate on a 4-point Likert scaie their level of agreement with each statement (0 = not at all true; 3 = very much true). It yields an ADHD

Index score and an ADHD DSM-IV Total score, with both inattentive and

Hyperactive subtype scores. Youth were ciassified into the Attentionai Deficits

(AD) group if their totai ADHD Index T score was 65 or greater, as recommended by the technical manuai (Conners, 2001). As stated by Conners

(2001), "The ADHD index contains the best set of items for distinguishing ADHD children from nonclinicai chiidren" (p.4). According to Conners (2001), in the normative sampie of adoiescent maies, the coefficient aipha for the ADHD

Index was .75. The coefficient aipha for the DSM-IV Totai scaie was .83. In the current sample, the coefficient alpha for the ADHD Index scale in was .81. The coefficient alpha for the DSM-IV diagnosis scale was .92 in the current sampie.

Dependent Measures

Reynolds Adoiescent Depression Scaie: The RADS • 2 (Reynoids, 2003) is a 30-item, paper-and-pencil, self-report scale used to measure depressive symptomatoiogy in youth aged 11 to 20 years. On the RADS-2, respondents indicate on a 4point Likert scaie the frequency of a particuiar feeiing or behavior (1 = Aimost never, 4 = Most of the time). Higher scores on this measure are indicative of more depressive symptoms. The four subscaies measure depressive symptomatoiogy in four domains (Dysphoric Mood, Anhedonia/Negative Affect,

Negative Seif-Evaiuation, and Somatic Compiaints). According to Reynolds

(2003), the RADS-2 has good reliability. Based on data from the normative sampie, the coefficient aipha for the RADS-2 was .92. in addition, test-retest coefficients of .80 and .79 were reported for the normative sampie. in this sampie, the coefficient aipha for the RADS-2 was aiso .92.

Piers- Harris Chiidren's Seif - Concept Scaie Second Edition: The PHCSCS-2 (Piers

a Herzberg, 2002) is an 60-item, self-report measure in which the respondents answer either "yes" or "no" to each question. The scaie was designed to assess seif-perceptions of one's own behavior and attitudes in youth aged 7 to 18

300

The Journal of Correctionai Education 58(3) • September 2007

O'Brien, e t ai Reading Probiems and Attentionai Deficits in Adolescent Maies years. The PHCSCS-2 has six subscaies (Behavioral Adjustment; Intellectual and

School Status; Physical Appearance and Attributes; Freedom from Anxiety;

Popuiarity; and Happiness and Satisfaction). Higher scores are indicative of a more positive self-evaluation across aii six domains. According to Piers and

Herzberg (2002), based on the standardization sampie, the totai scaie has an internai consistency of .91 and the individuai subscaies have internal consistencies that range from .74 and .81. This PHCSCS-1 was previously used with another sample at CAMP Robert J. Martin Youth Leadership Academy and the coefficient alpha was .94 (Langhinrichsen-Rohling et ai., 2005). Likewise, in the current sampie, the totai scaie had a coefficient aipha of .93. The coefficient aiphas for the individuai subscaies ranged from .68 to .84 in the present sampie.

Chiidren's Nowicki - Strickland internal-Externai Controi Scaie • Short Form: The

CNS - IE (Nowicki & Strickiand, 1973). The recommended short form for youth in 9th to 12th grade was administered. The short form Inciudes 21 of the items from the originai 40-item scaie. The scaie was designed to assess chiidren's perceptions of the degree of controi they have over the events in their iives. For each item the respondent is asked to indicate whether they beiieve each statement is "true" or faise". Higher scores on this measure are indicative of a more externai iocus of controi. This measure has been used previously in juvenile detention and aiternative sentencing settings. According to

Langhinrichsen-Rohiing et ai. (2005) in a previous study at CAMP Robert J.

Martin Youth Leadership Academy, the coefficient aipha for the CNS-iE was .76.

The originai scale has reported internai consistencies ranging from .68 (6th to

8th graders) to .74 (9th to 11th graders; Nowicki a Strickiand, 1973). The coefficient aipha for the short form in the current sample was .78.

Procedures

A parent or guardian must accompany each youth upon their arrivai and admission to the residentiai facility. At this time, according to the faciiity's internai procedure, aii parents are required to fill out an intake package, informed consent was obtained from parents during this procedure. No parents refused to have their chiid participate in this study. After obtaining parental consent, verbal and written assent was required from each youth prior to his participation. No youth refused participation either.

Each youth was to be assessed during their first or second week at the camp, because each spends these weeks in the evaiuation phase of the program. However, due to the avaiiabiiity of some of the youth (e.g., doctor's

301

The Joumai of Correctional Education 58(3)»September 2007

Reading Problems and Attentional Deficits in Adolescent Males O'Brien, et. al appointments, staff meetings, etc.), there was some variability in tiie time that the youth were actuaiiy assessed. On average, the youth were assessed after they had been at the camp for 1.76 weei<s (range: iess than 1 weei< to 6 weeks). A researcher administered the seif-report pacicet, which tooi< an average of forty-five minutes. During this time, the youth were aiso assessed using the Gates-MacCinitie Reading Tests - 4th Edition. Due to the suspected prevaience of reading difficuities in this popuiation, the items from each of the scaies in the seif-report package were provided on an individuai audiocassette recorder. Trained research assistants were aiso avaiiabie to assist the participants if they needed heip and to answer any questions they had. After compieting the survey, the youth were thanked for their participation, debriefed, and asked if they had any questions. Youth did not receive a written debriefing form in order to heip maintain the anonymity of their participation within the residentiai program.

Results

The first hypothesis examined the prevaience of reading probiems and attentionai difficuities in this sampie of deiinquent youth. According to their performance on the reading task, 44.6% of the sampie (45/101 boys) had a reading probiem (RP). This is six times the highest rate of reading disabiiities that have been reported in schooi sampies (Kronenberger a iVieyer, 2001).

According to their seif-reported responses to the CADS, 18.8% of the sample

(19/101) perceived themseives as having attentionai difficuities (AD). This is simiiar to the seif-report rate of a diagnosis of ADHD obtained by

Langhinrichsen-Rohiing et ai. (2005) in a comparabie sampie drawn from the same faciiity and is at ieast twice the rate that one wouid expect to find in the generai popuiation.

The second hypothesis asserted that adjudicated youth in RP oniy group, and adjudicated youth assigned to the AD oniy group wouid report more depression, iess positive seif-concepts, and a more externai iocus of controi than adjudicated youth in the No RP or AD group. The third hypothesis stated that the RP and AD (co-morbid) group wouid have more depression, iess positive seif-concepts, and a more externai iocus of controi than aii three other groups According to the operational definitions chosen in the current study, 47

(46.5%) of the maie juveniie offenders did not meet criteria for either a reading probiem or an attentionai deficit. These individuals comprised the No RP or AD group. Thirty-five (34.7%) of the remaining juvenile offenders met criteria for a reading probiem (RP Oniy group) whiie only nine offenders (8.9%) qualified for

302

The Joumai of Correctional Education 58(3) * September 2007

O'Brien, et. al Reading Problems and Attentional Deficits in Adolescent Males the AD Oniy group. The ten remaining juveniie offenders (9.9% of the sampie) met criteria for a reading probiem whiie simuitaneousiy seif-reporting significant ieveis of attentionai deficits. These individuais comprised the Comorbid group

(RP and AD).

Prior to determining whether there were mean differences among the four groups on the measures of depression, seif-concept, and iocus of controi, correlations were conducted to determine the degree of association among the dependent measures. The three juveniie justice program-reiated dependent variabies (i.e., depressive symptoms, seif-concept, and iocus of controi) were aii moderateiy correiated with one another in this sampie (r's ranged from .49 to

.72). Thus, an overaii between groups iVlANOVA was utiiized to compare the four groups on these three mentai heaith variabies simuitaneousiy.

in generai, resuits of the MANOVA reveaied that the boys in the four groups (RP oniy; AD oniy; RP and AD; No RP or AD) differed significantiy from one another in their seif-reports of depressive symptoms, seif-concept, and iocus of controi, Roy's Largest Root (3,95) = .451, p < .001. Furthermore, foiiowup univariate analyses of variance reveaied that group membership was significantiy reiated to ail three variabies, depressive symptoms, F (3,98) =

10.78, p < .001, eta2 = .25 ; seif-concept, F (3,98) = 12.60, p < .001, eta2 =

.28; and iocus of controi, F (3,98) = 5.53, p < .01, eta2 = .15. In fact, group membership accounted for 25%, 28% and 15% of the variance, respectiveiy.

As shown in Tabie 1, according to Tukey's Least Significant Differences post-hoc anaiyses, two of the variabies (depressive symptoms and seif-concept) showed the same pattern of group differences. Specificaiiy, for both these constructs, the AD Oniy and the RP and AD groups reported significantly more symptoms of depression and iess positive seif-concepts than either the No RP or

AD or the RP Oniy groups. Likewise, adjudicated youth in the AD Oniy group reported a significantly more externai iocus of controi than did adjudicated youth in either the No RP or AD or the RP Oniy groups. However, contrary to expectation, youth with both RP and AD did not have a significantiy more externai iocus of controi than youth in either of the one probiems groups, as had been hypothesized.

Because significant group differences were found on the overaii measure of seif-concept, foiiow-up anaiyses were conducted to consider group differences on the six subscales of the seif-concept scaie. An additionai iVIANOVA was performed, and, as expected, resuits confirmed that the groups differed significantiy overaii on the six seif-concept subscaies, Roy's Largest Root

(6,94) = .90, p < .001. Furthermore, foliow-up univariate anaiyses of variance

303

The Joumai of Correctionai Education 58(3) • September 2007

Reading Probiems and Attentional Deficits in Adoiescent Males O Brien, e t al

Tabie 1. iViean Differences in intake Symptoms Reported by Adjudicated iViales witii Reading Probiems Oniy, Attentionai Deficits Oniy, Both

Reading and Attentional Problems, or Neither Reading Probiems nor

Attentionai Deficits.

No Reading

Probiem or

Attentionai

Deficit

(n = 47)

Reading

Probiem

Oniy

Attentionai

Deficit Only

(n = 34) (n = 9)

RP and

AD

(n = 9)

F df

-

P

Eta^

Depression

M

SD

Seif-Concept

M

SD

Locus of Controi

M

SD

56,24^

13.54

46,623

8.69

7.08a

4.34

56.473

14.02

46.183

8.31

8023.C

3.75

74.08''

18.53

30.44"

9.19

12.22"

2,44

79,44"

9.85

34.67"

10,68

10.78"''^

4.27

10.78

12.60

5.53

98

98

98

.000

.254

.000

.285

.002

.149

Note: Means with different superscripts are significantiy different from one anotiier using Tuioy's Least

Significant Difference Post-Hoc Anaiysis.

revealed that group membership was significantly reiated to aii six types of seifconcept: 1) behaviorai adjustment (F (3,100) = 7,77, p < .001); 2) inteilectuai and school status (F (3,100) = 13.17, p < .001); 3) physical appearance and attributes,

(F (3,100) = 3.49, p < .05); 4) freedom from anxiety, (F (3,100) = 22.60, p < .001);

5) popuiarity, (F (3,100) = 6.73, p < .001); and 6) happiness and satisfaction, (F

(3,100) = 5.10, p < . 0 1 ) ,

However, as shown in Tabie 2, according to post-hoc anaiyses, the differences did not all conform to the prediction that the RP and AD group wouid be the most symptomatic, foiiowed by the RP oniy and the AD only groups, and then finally, the fewest symptoms wouid be reported by youth in the No RP or AD group, in fact, across aii six subscaies, there were no significant mean differences in self-concept subscaie reports between the RP oniy group and the No RP or AD group,

304

The Joumai of Correctionai Education 58(3)»September 2007

O'Brien, et. ai Reading Probiems and Attentionai Deficits in Adoiescent Males

Table 2. i^Aean Differences among the four groups on the

Concept Subscaies.

Piers-Harris Seif

Subscaie

NoRP or AD

(n = 47)

RP only

(n = 35)

AD Oniy

(n = 9)

RPand

AD

(n = 10)

F df P

Behaviorai

Adjustment

M

SD

8.97a

3,50

9.933

3.36

4.00"

2.55

7.703

3.40.

7,77 100 .000

.194

nteiiectuai

M

SD

12.463

2.56

11.383

3.37

6.22"

3.42

8.20"

4.37

13,17 100 .000

,289

Physicai

W

SD

Freedom from Anxiety

M

SD

9.593

1.95

11.513

2.60

9.403

1.83

11.423

2.41

7.33"

2.29

8.00"

2.69

8,503."

3,06

5,10c

2,13

3,49

22.60

100

100

.019

.098

.000

.411

Popuiar

M

SD

10.343

1.84

9.883."

1.81

8.56".C

3.36

7,19c

2,35

6.73

100 .000

.172

Happiness

M

SD

8.043."

1.79,

8.423

1.74

6.78".C

1.99

6,1 OC

2,60

5.10

100 .003

Note: Means with different superscripts are significantiy different from one another using Tukey's

Least Significant Difference Post-Hoc Anaiysis

.136

Interesting group differences were obtained for youth in the AD oniy group, however. These adjudicated youth saw themseives as the ieast behavioraiiy adjusted (significantly different from aii three other groups). Youth in this group aiso seif-reported that they perceived themseives to be significantly iess inteiiigent than youth in the RP oniy, or No RP or AD groups.

Youth in the AD oniy group did not differ in their inteiiigence seif-perceptions

305

The Joumai of Correctional Education 58(3)»September 2007

Reading Problems and Attentional Deficits in Adolescent Males O Brien, e t al from youth in the AD and RP group. Youth in the AD oniy group rated their physical seif-concept as iower than youth in the RP oniy or No RP or AD groups and they simiiarly perceived themseives to be significantiy iess free from anxiety about themseives. Youth with both RP and AD reported the ieast amount of freedom from seif-reiated anxiety, as their means on this subscaie differed significantiy from aii three other groups. iVloreover, as shown in Tabie

3, the magnitude of this effect was moderate, with group membership accounting for about 41 % of the variance in adjudicated youth s scores. With regards to popuiarity, resuits indicated that youth without RP or AD had the highest seif-concept popuiarity mean scores, and youth with both RP and AD conceived of themseives as significantiy iess popuiar than youth in any of the three other groups. Lastiy, youth in the AD Oniy group reported significantiy iower rates of happiness and satisfaction compared to youth in the RP Oniy group but did not differ in their ratings from youth in the RP and AD group.

Thus, no differences in seif-concepts were found between youth in the AD Oniy and youth in the RP and AD groups on the inteilectuai, physicai, popuiar, or happiness subscaies of the seif-concept measure. However, the AD Oniy group reported significantiy iower behavior seif-concepts than did the RP and AD group whiie the RP and AD group reported significantiy iess freedom from anxiety than the AD Oniy group.

in order to determine the effects of RP and AD, separateiy and combined, on the primary dependent measures, a higherarchicai iinear regression anaiysis was performed. The independent factor of RP was quantified as the discrepancy

(in years) between current grade ievei and the Gates-iViacCinnitie grade equivaient estimate. The CADS-A totai score was used to quantify ievei of AD.

Both independent variabie scores were mean centered to correct for probiems due to muiti-coiinearity. Because the DV s were moderateiy to strongiy correiated with one another, an aggregate variabie was created for the purpose of quantifying the degree of reported mentai heaith at intai<e. The intake mentai heaith variabie was formed by taking the z-score of the continuous measures of depressive symptoms and iocus of controi scores, adding those scores to the inverse z-score of the seif concept totai score, and dividing the resuit by three. The iinear regression reveaied that the overaii modei accounted for 58.3% of the variance in intake mentai heaith symptoms, F(3, 97) = 45.172, p < .001). Individuaiiy attentionai deficit symptoms yieided a beta weight of

.759, and accounted for a significant amount of the variance, r^partial = 57.76, p <.OO1. By contrast, reading probiems yieided a beta of .062, and accounted

306

The Joumai of Correctional Education 58(3) • September 2007

O'Briea et al Reading Problems and Attentional Deficits in Adolescent Males

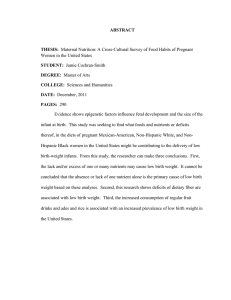

Figure 1. Plot of the interaction between AD symptoms and RD symptoms as predictors of intake mental health status. Because dependent measures were mean centered, data points represent the values

+/-1 SD from the mean of 0 when entered into regression equation:

-0.2

-0.4

-0.6

-0.8

-1

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

- RDLOW

ADHDLOW

-0.4681

ADHDHIGH

0.5827

for less than one percent of the variance in intake mentai heaith symptoms (p

>.O5). interestingly, the interaction between AD and RP produced a beta weight of .127, and accounted for 3.6% of the variance (p = .058). Anaiysis of the interaction indicated that individuais who were high in AD symptoms demonstrated no effect of RD on their intake mentai heaith, while individuais who were low in AD symptoms had higher intake mentai heaith scores if they had higher levels if reading deiay, and iower intake mentai heaith scores if they had lower ieveis of reading deiay (see Figure 1). This suggests that RD may have an effect on mental health, but that this effect is masked by the more dramatic effect of AD symptoms.

307

The Joumai of Correctional Education 58(3) • September 2007

Reading Problems and Attentional Deficits in Adolescent Males O Brien, e t al

Discussion

This study considered the prevaience rates of reading probiems and attentional difficuities in adjudicated maie adolescents residing in an aiternative sentencing program. As hypothesized, a iarge proportion of this sample (44.6%) met criteria for a reading probiem. in fact, our obtained rate was comparabie to the rate of 43% reported by Finn et ai. in 1988 in an independent sampie of deiinquent youth. This finding highiights the continuing need to provide educationai assessments and reading remediation opportunities to youth who are invoived in the juveniie justice system.

Contrary to expection, the majority of youth who were evaluated as having a reading probiem did not seif-report co-occurring attentionai difficuities.

Instead, the majority of youth with reading probiems were piaced in the RP oniy group. iVloreover, the obtained data did not support the supposition that adjudicated youth with reading probiems, but no seif-reported attention deficits, wouid report more depressive symptoms, reduced seif-concepts, and a greater externai iocus of controi at intake when compared to other adjudicated youth without reading and attentionai problems. For example, adjudicated youth in the RP Oniy group did not report significantiy more symptoms of depression than youth in the No RP or AD group. iVloreover, the mean raw score on the depression inventory did not meet a ciinicai ievel of depressive symptomatoiogy for the RP Oniy group (Reynoids, 2003). This finding is simiiar to recent studies that have found that the relationship between reading disabiiity and depression is not significant when the effects of ADHD are controiied for (Wiicutt & Pennington, 2000; Maughan et ai., 2003). However, one important possibiiity for expiaining the current resuit is that it is iikeiy that many participants in this sample who were behind in reading had not been afforded ampie educationai opportunity. They may have grown up in environments where their reading difficuities wouid be iess apparent and perhaps, as a resuit, be iess iikeiy to engender concominant psychosocial difficuities.

Aiso, the RP Only group did not differ from the No RP or AD group in their reports of seif-concept or locus of control. These resuits are divergent from research which has focused on mentai health differences between iearning disabied and non-iearning disabied youth in the generai popuiation. For exampie, in 1985, Rogers and Sakiofske compared the seif-reported selfconcepts and loci of control between youth with and without a iearning disabiiity. They reported that the iearning disabled youth had iower giobai selfconcepts and a more externai iocus of controi. in addition, Tabassam and

308

The Joumai of Correctional Education 58(3)«September 2007

O Brien, e t al Reading Problems and Attentional Deficits in Adolescent Males

Grainger (2002) found that eiementary chiidren with LD or comorbid LD/ADHD had iower academic seif-concepts, poorer academic efficacy, and more negative peer reiated seif-concepts than comparison groups. Furthermore, Tarnowski and

Nay (1989) found that LD and LD/ADHD youth were more likely to externalize their probiems. However, a number of important differences exist between the current study and these previous findings. First, most previous work has more focused on a generaiized but diagnosabie iearning disabiiity rather than a specific probiem with reading. iViore negative associations may be found in conjunction with a broader conceptualization of the iearning disabiiity. Second, none of the previous work has iooked at these associations in sampies of adjudicated youth who are invoived in the juveniie justice system, it may be that within a deiinquent sampie, having a reading probiem (which is quite common in this setting) has little to no effect on the youth's current mental heaith status and functioning. Third, comparisons among studies are made difficuit by the iack of an agreed upon strategy for determining reading probiems and attentionai difficulties. Finaiiy, the interaction pattern obtained in the finai anaiysis suggests that reading problems have an effect on mental health functioning at intake oniy when the youth exhibits iow ievels of ADHD symptoms. These effects disappear when the youth is experiencing high levels of ADHD symptoms. Thus, future research is needed to fuiiy understand what, if any, juveniie justice program reiated ramifications, can be directiy attributed to a youth's reading probiems.

As hypothesized, a sizeabie minority of the adjudicated maie youth met criteria for a seif-reported attentionai deficit. In fact, the obtained rate of 18.8% is very similar to the rate of 19.6%, which was previously found, using seifreports of receiving an ADHD diagnosis, in a separate sampie of youth from the same facility (Langhinrichsen-Rohling et al., 2005). While seif-report measures are clearly not the preferred method for determining a diagnosis of ADHD (e.g..

Root & Resnick, 2003), and are quite iikeiy to underestimate the extent of the problem (e.g., Danckaerts, 1999); they may stiii provide an efficient and reliabie way to identify adjudicated youth who are aware of their attentionai difficulties.

Of the youth seif-reporting attentionai problems, approximateiy haif aiso met criteria for a reading probiem. The remainder did not. Consequentiy, one take home message from this study might be that adjudicated youth who self-report attentionai deficits shouid automatically be flagged for a reading disabiiity assessment. These problems may share some common mechanisms. However, an alternative explanation is that it may be more difficuit for adjudicated youth with attentionai problems to perform their best academicaliy in a group

309

The Joumai of Correctional Education 58(3) • September 2007

Reading Problems and Attentional Deficits in Adolescent Males O'Brien, e t al residential setting. Future research wiii be needed to tease out these different possibiiities.

it was hypothesized that the AD Only group wouid report significantly more negative psychoiogicai symptoms than would adjudicated youth in the

No AD or RP group. In general, this hypothesis was supported by these findings, as youth in the AD Only group reported more depressive symptoms, lower self-concepts, and a more external locus of controi than did youth in the

No RP or AD group. The regression analysis also confirmed the importance of measuring adjudicated youth's perceptions of attentionai deficits as the AD variable accounted for 56.5% of the variance in a composite measure of adjudicated youth's mentai heaith probiems at intake. These findings replicate previous studies that have found a diagnosis of ADHD to be related to higher rates of depression, iower self-concepts, and a more external locus of control in both adjudicated and non-adjudicated samples (Langhinrichsen-Rohiing et al.,

2005; Lufi 8 Parlsh-Piass, 1995; Wiicutt 9 Pennington, 2000). Furthermore, the mean raw RADS-2 score of the AD Oniy group would place these youth within the ciinicai ievel of depressive symptoms (Reynolds, 2003). Likewise, based cutoffs published for the Piers-Harris self-concept scores, adjudicated youth in the

AD Oniy group couid be described as having iow self-concepts (Piers &

Herzberg, 2002). Taken together, these findings suggest that some delinquent youths' attentional concerns can be identified via the use of a quick and efficient self-report measure and that this identification is associated with other program-related mental health symptoms.

Approximateiy ten percent (9.9%) of the adjudicated male youth met criteria for both reading probiems (RP) and attentional deficits (AD). A priori, it was hypothesized that the comorbid group wouid report significantiy more negative psychoiogicai symptoms than youth in any of the three other groups.

This hypothesis was oniy partially supported by the findings. Generaiiy, as expected, the co-morbid, RP and AD group was found to have more probiems

(greater endorsement of depressive symptoms, reduced seif-concepts, more external locus of control) than the no RP or AD and/or the RP only groups, but they did not aiways differ from youth in the AD oniy group as had been hypothesized. In fact, based on the general absence of differences between the

RP and AD group and the AD Only group obtained in this research, one potential conclusion to consider is that having attentional deficits, with or without a reading disability, may be particuiariy detrimental to the current mental health status of adjudicated youth entering an alternative sentencing residentiai setting.

310

The Joumai of Correctional Education 58(3) • September 2007

O'Brien, e t al Reading Problems and Attentional Deficits in Adolescent Males

Limitations

However, severai limitations of this study needed to be articulated. First, the sample in the current study oniy inciuded adjudicated maies who were sentenced to alternative sentencing program. Therefore, the findings may not generalize to female juveniie deiinquents or to youth in other parts of the juveniie justice system. Future studies that include both maie and female youth in all aspects of the juveniie justice system are needed to determine If these results hold across gender and setting. Second, this study took place in an alternative sentencing program in the Southeastern United States, which limits the generaiizability to other geographical locations. Third, as mentioned previousiy, there are various forms of assessment procedures that are currently utilized in order to diagnose reading disabilities and there are muitipie ways to assess attentionai difficulties and ADHD. In this study, assessment strategies were chosen based on ease of administration (i.e. less time, less training to administer) and on prior research findings. However, using these methods precluded a determination of a formai diagnosis. Thus, future research is recommended to repiicate these findings with more stringent assessment strategies that would allow the functioning of youth with actual diagnoses to be compared. Fourth, the degree to which these assessment measures are appropriate for use in low SES, delinquent and/or adjudicated sampies requires additional investigation. For example, future studies should investigate the concurrent validity of the Cates • MacCinitie Reading Tests - Fourth Edition

(MacCinitie & MacGinitie, 2000) with the reading composite score of the

Wechsier Individuai Achievement Test- II (Psychological Corporation, 2002), in order to determine the usefuiness of the GMRT-4 with deiinquent youth. Future research that investigates the concurrent validity of the Conners' - ADHD/DSM -

IV Scales - Adolescent (Conners, 2001) with the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Chiidren (Shaffer et ai., 1996) in delinquent populations wouid aiso be usefui. Finally, this study reiied heavily on data gathered via self-report and some of the findings reported here may be due to method bias (i.e., symptomatic children are more likely to report symptoms across aii the selfreport measures). Utilizing a muiti-trait, multi-method, multi-informant design wouid add considerabiy to the vaiidity of these findings.

Clinical Implications

Overall, however, the results from the current study support previous findings that the prevalence of reading probiems and attentional deficits in juveniie delinquents is considerable. On one hand, these findings highiight the need for

311

The Joumai of Correctional Education 58(3) • September 2007

Reading Problems and Attentional Deficits in Adolescent Males O'Brien, e t al regular assessment of disabilities for youth in the juvenile justice system. In order to comply with IDEA requirements, proper assessment and identification of disabiiity is necessary if disabled youth are going to be eligible to receive speciai education services. If more delinquent youth are properly identified as experiencing a disabiiity, even short-term juvenile justice faciiities might be eiigibie for funding to support additionai educationai interventions for these youth. According to Rutherford et al. (2002), funding for educational programs is, in part, determined by the number of youth who are identified with a special education disability. Thus, through assessments could help to increase funding for appropriate services while youth are adjudicated. However, in order to appropriateiy identify disabiiities within deiinquent youth, a push must be made for standard definitions of disabiiities and customary assessment procedures across settings (i.e. schools, mental health centers, juvenile justice system). In order to accomplish this, Rutherford et al. (2002) suggested

(a) selection of existing instruments based on content-relevance and psychometric characteristics for use in a screening battery, (b) development of procedures to link administrative intal<e and placement procedure with assessment results and transfer to educationai and social interventions, and (c) continuing assessment of each individuai while in custody to adjust and improve intervention efforts (p.22).

On the other hand, findings from this study also strongly support the need for routineiy assessing the psychoiogicai well being of deiinquent youth. Determining who meets criteria for difficulties with attention might be particularly important as these youth are more likely to have depressive symptoms, lower self-concepts, and an extemal locus of control. These symptoms may also interfere with the youth s ability to transition successfuiiy through a juvenile justice facility and to remain crime-free once they are released from the program. Previous research suggests that without appropriate services, deiinquent youth with ADHD are more iikeiy to be repeat offenders (Moffitt, 1990). The Nationai Councii on Disability (2003), outiines principles for effectiveiy intervening with youth with disabiiities in the juveniie justice system. These principles inciude using vaiidated assessment instruments, employing cognitive behavioral interventions, using interventions that are cuiturally appropriate, accessing community resources, and providing aftercare services upon release. According to these data, these services are particuiariy needed for adjudicated youth who are suffering with attentional deficits, whether or not they concurrentiy suffer with a reading problem.

312

The Joumai of Correctional Education 58(3) • September 2007

O'Bn'en, e t al Reading Problems and Attentional Deficits in Adolescent Males

References

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders

(4th ed. - Text Revision). Washington, DC: Author.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statisticai manuai of mentai disorders

(4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Archwamety, T, & Katsiyannia, A. (2000). Academic remediation, paroie vioiations, and recidivism rates among deiinquent youths. Remediai and Spedai Education, 21,161-170.

Atl<inds, D. L., Pumariega, A. J., Rogers, K., iVlontgomery, L, Nybro, C, Jeffers, C, & Sease, F.

(1999). iV^entai heaith and incarcerated youth, i: Prevaience and nature of

psychopatho\ogy. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 8, 193-204.

Barl<Iey, R.A. (1990). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder New York: Guilford.

Brunner, M.S. (1993). Reduced recidivism and Increased empioyment opportunity through

research-based reading instniction. (NO Pubiication No. 141324). Washington, DC: Office of Juveniie Justice and Deiinquency Prevention.

Conners, CK. (2001). Conners'Rating Scaies-Revised. North Tonawanda, NY: iViuiti-Heaith

Systems.

Danckaerts, iVI., Heptinstail, E., Chadwick, O., a Tayior, E. (1999). Self-report of attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder in adoiescents. Psychopathology, 32, 81-92.

Finn, J.D., Stott, iVI.W.R., & Zarichny, K.T. (1988). School performance and adoiescents in juveniie court. Urban Education, 23,150-161.

Frederickson, N., & Jacobs, S. (2001). Controilabiiity attributions for academic performance and the perceived schoiastic competence, giobai self-worth, and achievement of chiidren with dysiexia. Schooi Psychoiogy internationai, 22, 401-406.

Hinshaw, S.P. (1992). Externaiizing behavior problems and academic underachievement in chiidhood and adoiescence: Casuai reiationships and underiying mechanisms.

PsychoiogicaiBuiietin, 111, 127-155.

Hoza, B, Mrug, S., Gerdes, A. C, Hinshaw, S., Bukowski, W., Coid, J. A., Kraemer, H., Peiham,

W. E., Wigai, T, a Arnoid, L E. (2005). What aspects of peer reiationships are impaired in chiidren with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? Journal of Consuiting

and Ciinicai Psychoiogy, 73, 411-423.

Hoza, B., Waschbusch, D.A., Peiham, W.E., Moiina, B.S.C., a iWilich, R. (2000). Attention-

Deficit/Hyperactivity Disordered and controi boys' responses to sociai success and faiiure. Chiid Deveiopment, 77, 432-446.

Kronenberger, W.G., a iVIeyer, R.G. (2001). The chiid dinician's handbooi( (2nd ed.). Boston:

Aiiyn a Bacon.

Langhinrichsen-Rohiing, J., Rebhoiz, C L., O'Brien, N., O'Fan-iil-Swaiis, L, a Ford, W. (2005). Seifreported co-morbidity of depression, ADHD, and aicohoi/substance use disorders In maie youth offenders residing in an aitemative sentencing program. Journai cf Evidence-

Based Sociai Work: Advances in Practice, Programming, Research, and Policy, 2,1 -17

Lufi, D., a Parish-PIass, J. (1995). Personaiity assessment of chiidren with Attention Deficit

Hyperactivity Disorder. Journai of Ciinicai Psychoiogy, 51, 94-99.

313

The Joumai of Correctional Education 58(3) • September 2007

Reading Problems and Attentional Deficits In Adolescent Males O'Briea e t al

MacCinitie, W., a MacGinitie, R. (2000). Gates-MacGinitie Reading Tests (4th ed.). itasca, iL:

Riverside.

Maguin, E.., Loeber, R., a Lemahieu, P.G. (1993). Does the reiationship between poor reading and deiinquency hold for maies of different ages and ethnic groups? Journai

of Emotionai and Behaviorai Disorders, 1, 88-99.

iVIaughan, B., Rowe, R., Loeber, R., a Stouthamer-Lober, M. (2003). Reading probiems and depressed mood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 31, 219-229.

iVIayfield Arnoid, E., Goidston, D.B., Walsh, A.K., Reboussin, B.A., Daniei, S.S., Hickman, E., a

Wood, F.B. (2005) Severity of emotionai and behaviorai problems among poor and typicai readers. Journal of Abnormal Chiid Psychoiogy, 33, 205-217

Moffitt, T.E. (1990). Juvenile deiinquency and attention deficit disorders: Boys' deveiopmentai trajectories from age 3 to age 15. Child Development 61, 893-910.

Moffitt, TE., a Silva, P.A. (1988). Seif-reported deiinquency, neuropsychologicai deficit, and history of attentiori deficit disorder. Journai of Abnormai Chiid Psychoiogy, 16, 553-569.

Nationai Councii on Disabiiity (2003). Addressing the needs of youth with disabiiities in the juveniie justice system: The current status of evidence-based research.

Washington, DC: Nationai Councii of Disability. Retrieved March 5, 2004 from http:www.ncd.gov.newsroom/pubiications/juveniie.htmi.

Nowicki, S., a Strickland, B.R. (1973). A locus of controi scaie for chiidren. Journai of

Consulting and Oinical Psychology, 40,148-154.

Otto, R., Greenstein, J. J., Johnson, M. K., a Friedman, R. M. (1992). Prevalence of mentai health disorders among youth in the juveniie justice system. In J. Cocozza (Ed.),

Responding to the mentai heaith needs cf youth in the Juveniie justice system (pp. 7-48).

Seattle, WA: The Nationai Coaiition for the Mentaiiy III in the Criminai Justice System.

Pennington , B.F (1991). Diagnosing learning disorders: A neuropsychologicai framework. New

York: Guiiford.

Piers, E. V. a Herzberg, D.S. (2002). Piers Hanis Self-Concept Scaie, Second Edition. Los Angeles:

Western Psychological Services.

Psychological Corporation. (2002). Wechsler individuai Achievement Test, Second Ed. San

Antonio, TX: Psychoiogicai Corporation: Harcourt Assessment Company.

Reynoids, W. (2003). The Reynoids Adoiescent Depression Scaie, Second Ed: Professionai Manuai.

Odessa, FL: Psychoiogicai Assessment Resources.

Rogers, H., a Saklofske, H. (1985). Self-concepts, locus of controi, and performance expectations of iearning disabled chiidren. Journai of learning Disabiiities, 18, 237-278.

Root, R. W., a Resnick, R. J. (2003). An update on the diagnosis and treatment of Attention-

Deficit/Hyperactivity disorder in chiidren. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice,

34, 34-41.

Rotter, J. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus externai control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs: General 8 Appiied, 80(1), 1-28.

Rutherford, R.B., Jr., Bullis, M., Anderson, C, a Griller-CIark, H.M. (2002). Youth with

314

The Journal of Correctional Education 58(3) * September 2007

O'Brien, e t al Reading Problems and Attentional Deficits in Adolescent Maies

disabilities in the correctional system: Prevaience rates and identification issues. College

Park, MD: Center for Collaboration and Practice, American Institutes for Research.

Sattier, J.M. (2002). Assessment of Chiidren: Behaviorai and Oinicai Appiication (4th ed.). San

Diego, CA: Author.

Shaffer, D., Fisher, P., Dulcan, M. K., Davies, M., Picacentini, J., Schwab-Stone, M., Lahey, B.,

Bourdon, K., Jensen, P., Bird, H., Canino, C, a Regier, D. (1996). The NIMH Diagnostic

Interview Schedule for Children Version 2.3 (DISC 2.3): Description, acceptability, prevalence rates, and performance in the IVIECA study. Journai of the American

Academy of Chiid and Adoiescent Psychiatry, 35, 865-77

Smith, B. H., Pelham, W. E., Gnagy, E., Molina, B., 8 Evans, S. (2000). The reliability, validity, and unique contributions of self-report by adolescents receiving treatment for

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity disorder. Journai of Consulting and Oinicai Psychology, 68,

489-499.

Stanovich, K. E., a Siegei, L. S. (1994). Phenotypic performance profile of children with reading disabilities: A regression-based test of the phonological-core variabledifference model. Journai qf Educationai Psychoiogy, 86, 24-53.

Tabassam, W., a Grainger, J. (2002). Self-concept, attributional style and self-efficacy beliefs of students with learning disabilities with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Learning Disability Quarteriy, 25,141-151.

Tarnowski, K.J., a Nay, S.M. (1989). Locus of control in children with learning disabilities and hyperactivity: A subgroup analysis. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 22, 381-383.

Teplin, L (1990). Detecting Disorder: The Treatment of Mentall Illness Among Jail

Detainees. Journai ofConsuiting and Ciinicai Psychoiogy, 58(2), 233-236.

Wiicutt, E.G., a Pennington, B.F. (2000). Psychiatric comorbidity in chiidren and adoiescents with reading disability. Journai of Chiid Psychoiogy and Psychiatry, 41,1039-1048.

Biographical Sketches

Dr. JENNIFER LANCHINRICHSEN-ROHLINC is a Professor of Psychology at the

University of South Alabama. Currently, she is the Co-Principal Investigator of the Youth

Violence Prevention Program, which represents a research partnership between the

University and the Community. Dr. L-R has authored over 70 empirical papers and book chapters on adolescent risk behaviors and intimate partner violence.

JOHN F. SHELLEY-TREMBLAY, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of Psychology at the

University of South Alabama. His research investigates the interaction between visuai attention and reading processes by empioying psychophysiological, neuropsychological, and educational methodologies.

NATALIE O'BRIEN, M.S., is the co-author of numerous research papers. She is currently a research associate for the 3-C institute for Social Development in Cary, NC.

315