-

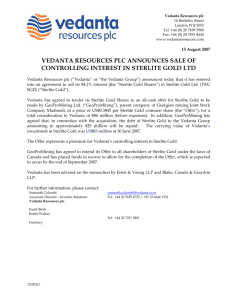

advertisement