Document 11206717

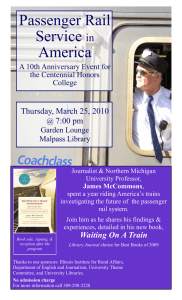

advertisement