Does “What We Do” Make Us “Who

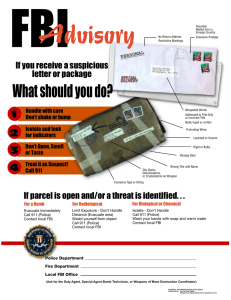

advertisement