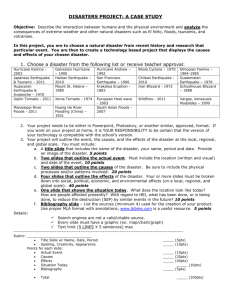

Private Sector Strengths Applied Good practices in disaster risk reduction from Japan 2013

advertisement