P F A SYCHOLOGICAL

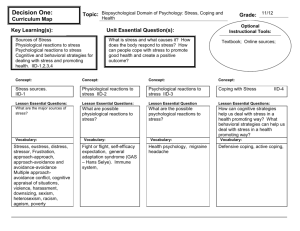

advertisement