Historical Events and Supply Chain Disruption:

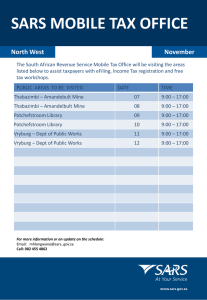

advertisement