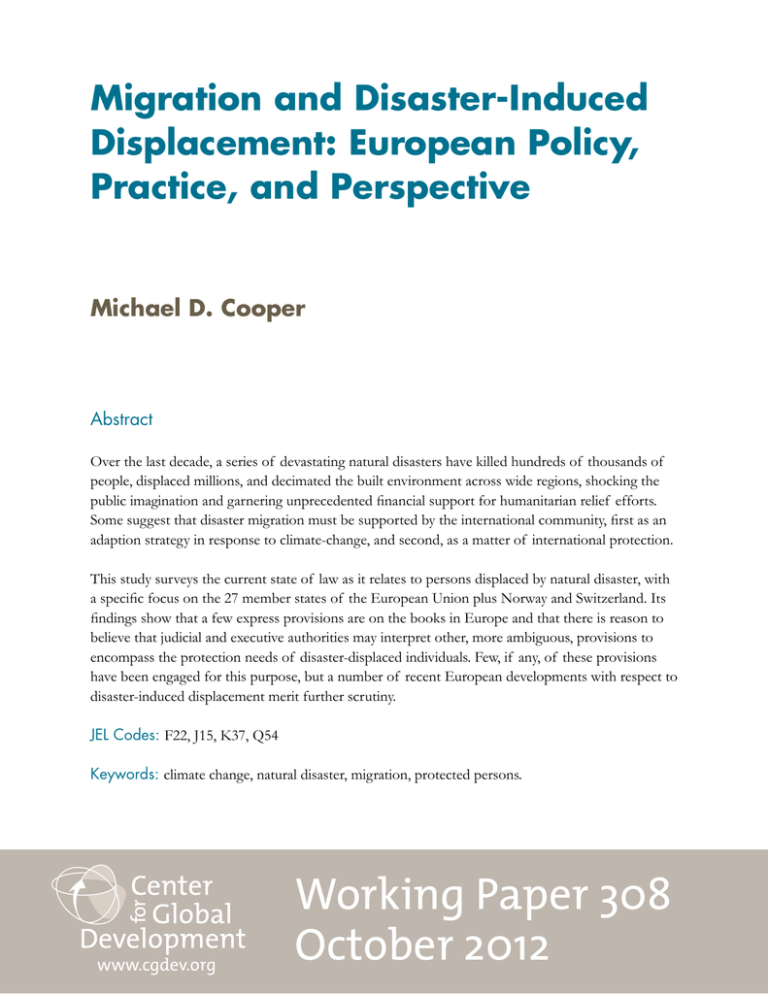

Migration and Disaster-Induced Displacement: European Policy, Practice, and Perspective Michael D. Cooper

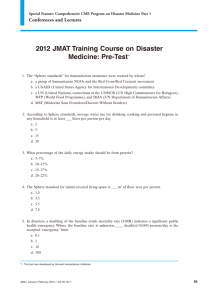

advertisement