Property Tax Incidence in Multifamily Rental ... 1995 Nadine Fogarty B.A. Geography, 1994

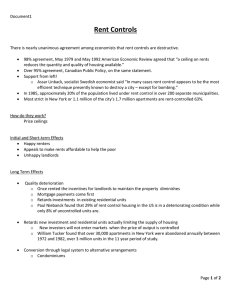

advertisement