Document 11168521

advertisement

^KCHE^N

><

M (UBRABIES.

©

Digitized by the Internet Archive

in

2011 with funding from

Boston Library Consortium

Member

Libraries

http://www.archive.org/details/whydidwestextend00acem2

HB31

M.415

working paper

department

of economics

WHY DID THE WEST EXTEND THE FRANCHISE?

DEMOCRACY, INEQUALITY AND GROWTH

IN HISTORICAL

PERSPECTIVE

Daron Acemoglu

James Robinson

No.

97-23

November 1997

,

massachusetts

institute of

technology

50 memorial drive

Cambridge, mass. 02139

WORKING PAPER

DEPARTMENT

OF ECONOMICS

WHY DID THE WEST EXTEND THE FRANCHISE?

DEMOCRACY, INEQUALITY AND GROWTH

IN HISTORICAL

PERSPECTIVE

Daron Acemoglu

James Robinson

No.

97-23

November 1997

,

MASSACHUSETTS

INSTITUTE OF

TECHNOLOGY

50 MEMORIAL DRIVE

CAMBRIDGE, MASS. 02139

JAN 1 9

1998

UBRABES

Why

Did the West Extend the Franchise?

Democracy, Inequality and Growth in

Historical Perspective*

James A. Robinson*

Daron Acemoglu^

First Version:

Revision:

August 1996

November 1997

Abstract

During the nineteenth century, most Western societies extended the franchise, a

decision which led to unprecedented redistributive programs. We argue that these

political reforms can be viewed as strategic decisions by political elites to prevent

widespread social unrest and revolution. Political transition, rather than redistribution under existing political institutions, occurs because current transfers do not

ensure future transfers, while the extension of the franchise changes the future

cal equilibrium

and acts

as a

commitment

to future redistribution.

Our theory

politi-

offers

a novel explanation for the Kuznets curve, whereby the fall in inequality follows redistribution due to democratization. We characterize the conditions under which an

economy experiences the development path associated with the Kuznets curve, as

opposed to two non-democratic paths; an "autocratic disaster" with high inequality

,

and low output; and an "East Asian Miracle", with low inequality and high output.

Keywords: Democracy, Enfranchisement, Growth,

Inequality, Political

Commit-

ment, Redistribution, Revolution.

JEL

Classification: D72, 015.

*

We would like to thank two anonymous referees, Claudia Goldin, Peter Lindert, Torsten Persson,

Dani Rodrik, John Roemer, Peter Ternin, Jaume Ventura, Michael Wallerstein and seminar participants

at Boston University, Cornell, Harvard, NBER, Universidad de los Andes, Singapore National University

and the World Bank for helpful comments and suggestions.

t Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Department of Economics, E52-371, 50 Memorial Drive, Cambridge, MA 02142; e-mail: daron@mit.edu

t

University of Southern California, Department of Economics, Los Angeles, CA 90089; e-mail:

arobinsSusc

edu.

j

.

Introduction

1

The nineteenth century was a period

and unprecedented

of fundamental political reform

changes in taxation and redistribution. For example, British society was transformed from

an "autocracy" run by an

The

a democracy

elite to

franchise

was extended

in 1832, then

again in 1867 and 1884, a process which transferred voting rights to portions of the society

which did not previously have any

political representation.

The decades

after the political

reforms witnessed radical social reforms, increased taxation and the extension of education to the masses.

noted by Kuznets, inequality, which had previously been

Finally, as

increasing, started to decline during this period: the Gini coefficient for

in

England and Wales had

Two

1901.

skilled

risen

from 0.400

in

income inequality

1823 to 0.627 in 1871, and

fell

to 0.443 in

key factors in the reduction in inequality were the increase in the proportion of

workers (Williamson, 1985), and redistribution towards the poorer segments of the

society; for example, taxes rose

from 8.12% of National Product in 1867 to 18.8% by 1927,

and the progressivity

system was increased substantially (Lindert, 1989). During

of the tax

the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the franchise was also extended in most

other Western societies. Those for which data exist

(e.g.

France,

Germany and Sweden)

show that democratization was followed by increased redistribution and the downturn

of

the Kuznets curve. 1

These events are hard to tmderstand with our existing models.

likely to lead to increased taxation

why should

the

political power,

In particular,

elite

and redistribution

extend the voting rights?

(e.g.

If

democratization

is

Meltzer and Richard, 1981),

Our answer

is

that the

elite,

who

held

were forced to extend the franchise because of the threat of revolution. 2

we argue

that democratization alters future political equilibria by changing

the identity of the median voter, thus acts as a commitment to future redistribution,

and prevents

social unrest.

In contrast to democratization, the promise by the elite to

redistribute in the future while maintaining political power

paradoxically,

we

find that in economies

promise of future redistribution

1

A

is

more

is

where the masses are

credible,

and so the

not credible.

Somewhat

politically organized, the

elite

can avoid a revolution

the U.S..

We

threat of revolution can intensify either because inequality increases (see for example Muller

and

country which exhibits a Kuznets curve, but some time after

full

democratization

is

return to this case in the concluding section.

2

The

on the strongly positive relation between income inequality and

because of some unusual event such as wars, depressions and famines.

Seligson, 1987,

political instability) or

without extending the franchise. This

may

why

explain

in the nineteenth century, while

Britain and France extended the franchise in the face of heightened social unrest and

inequality,

Germany which had

the most organized working class in Europe instituted the

much

welfare state, but did not extend voting rights until

First

later (after the turmoil of the

World War).

The second

contribution of our paper

and the Kuznets curve.

was an important

We

is

between democratization

to point out the link

argue that the increase in inequality in Western economies

which led to the extension of the fran-

factor in increased social unrest

Democratization, in turn, increased redistribution and was instrumental in reducing

chise.

inequality.

As predicted by our approach,

in Britain, France,

Germany and Sweden,

peak of the Kuznets curve coincides with the extension of the franchise.

model explains the Kuznets curve,

ture of

all

it

the

Although our

does not predict that this pattern should be a fea-

development processes (which accords with the empirical findings of Anand and

Kanbur, 1993;

Fields, 1995;

and Fields and Jakubsen, 1993). Instead we predict that a

Kuznets curve should be observed when a society democratizes due

to social pressure. Al-

ternative development paths, the "autocratic disaster" and the "East Asian miracle", do

not feature Kuznets curves.

In an autocratic disaster inequality

is

high, but there

democratization or redistribution because the masses are badly organized.

of the masses slows

down accumulation and

economy

leads the

of output. In an East Asian miracle initial inequality

is

is

no

The poverty

to stagnate at a low level

low, so the

economy accumulates

rapidly and converges to a high level of output, and because the gains from growth are

more equally shared,

reform

is

social pressure does not

until

much

later,

and thus

political

considerably delayed.

Our paper belongs

we

emerge

to the growing literature

on

political

economy and growth. However,

are aware of no other paper which shares our two key points: franchise extension as a

commitment

conflict.

device,

Among

provides the

and the Kuznets curve

the important contributions related to our work are

first

elite.

who

investigate a

Our paper

(1993)

Roemer

by

social

(1985)

who

economic model of revolution; Grossman (1991;1993;1995), who models

predation by the unprivileged against the

(1993),

as a result of political reform caused

is

rich;

model where there

also closely related to

is

and Ades (1995) and Ades and Verdier

concentration of power in the hands of an

Benabou

(1996), Galor

and Zeira (1993), Perotti

and Banerjee and Newman (1993) who model investment opportunities as

and thus show that distribution of income matters

for

indivisible

growth and development. In

fact,

our model in Section 3 builds on Galor and Zeira (1993). Finally, our contribution shares

a

common theme

with North and Weingast (1989)

who

also argue that political reform

can be a method of commitment, but in the context of the introduction of the English

Parliament in the seventeenth century.

The plan

power

is

of the paper

is

In Section

as follows.

concentrated in the hands of an

elite

we develop a model where

2,

and the masses can

political

a revolution to

initiate

We show that the elite can prevent a revolution either by redistributing,

the franchise. We characterize the conditions under which current and

contest this power.

by extending

or

promised future redistribution are not

commitment

3,

to future redistribution, the extension of the franchise,

we simplify

this

model

in a

number

that an increase in inequality can

of inequality

make

in

and output

of dimensions

make

we return

4,

in our analysis.

which a Kuznets curve

in this model.

A

is

Model

how a Kuznets

outline

and

curve, an autocratic

arise along the equilibrium path. In

many

justify

of the assumptions

than the U.S.)

some

extensions. Section 6 concludes.

of Democratization

consider an infinite horizon

economy with a continuum

while the remaining

—

1

A

of agents.

A form a rich

proportion A of

Throughout the

,

paper superscript p

denote poor agent and r

will

denote rich agent (or

poor agents as

and

all

We

elite).

identical.

that

if

asset,

will

will treat all

Initially, political

there

There

is

is full

power

is

1

identical,

"elite"

members

democracy, the median voter

will

.

member

of the

of the elite will also be

concentrated in the hands of the

elite,

but A

>

be a poor agent.

h (which should be thought as a combination of human and physical capital).

and each member

exogenous

(so

of the elite has

we drop time

t

first is

subscripts).

a market technology,

capital devoted to market production.

=

We

where each poor agent has human capital

h rQ > h% >

1.

In this section these stocks will be

Accumulation

There are two methods of producing the

The

\ so

a unique consumption good y with price normalized to unity, and a unique

begin our analysis of the economy at time

ital.

we

detected the peak coincides with political reform triggered by

these agents are "poor"

/iq

We show

The Environment

2.1

We

We

also argue in this section that for countries (other

social unrest. Section 5 briefly discusses

2

necessary. In Section

the revolution a threat, and analyze the dynamics

to the historical evidence,

We

is

and thus a firm

and add capital accumulation.

an East Asian miracle and a revolution may

disaster,

Section

sufficient to stave off a revolution,

final

is

investigated in Section

3.

good. Both techniques are linear in cap-

Y m = AH™

t

The second

is

where

H™

is

the

amount

of

human

an "informal", or home production

Y h = BH'

technology:

sector

is

,

where Hj*

H

=

Jh

l

of

human

We

di.

role of

l

t

t

for

,

=

i

p,r,

where r

/3

specific,

hence

T

6

(0,1).

by a

in our analysis

is

to

Post-tax income

We

t

m where we have

constraint therefore implies T = r AH

m can be taxed. 3

capital used in market production, H

t

given by,

is

T >

is

t

y\

=

the transfer

assume throughout that taxes and transfers

and r are not indexed by

t

t

linear indirect utility function

the tax rate on income, and

is

t

that the agent receives from the state.

cannot be person

B, so the market

not taxable.

is

over net income, and a discount factor

— T )Ah + T

A>

assume that

home production

All agents have identical preferences represented

(1

home produc-

capital used in

than 100%, because while taxes can be imposed on the

less

home production

sector,

amount

the

The only

always more productive.

ensure an equilibrium tax rate

market

is

+ H™ =

we have H^

Naturally,

tion.

l

t

t

,

i.

The government budget

used the fact that only

human

,

The "masses"

(A poor agents),

endowed with a revolution

though

excluded from the political process, are

initially

Since they form the majority, they can overthrow

technology.

the existing government and take over the means of production,

any period

t

>

We

0.

assume that

poor only retain a fraction

the previous

analysis,

nothing after a revolution). In particular,

agent receives a per period return of

total wealth in the

economy

between A agents.

A

whether

fi t _i

may be more

=

h

fi

attempted,

is

\x t

we assume,

if

there

AHj\

AH, and

it

always succeeds, but the

is

partially kept

is

a revolution at time

t,

This

in all future periods.

then each poor

is

of this

fi t

because the

and share

low value of y implies an ineffective revolution technology

h

and y

/j

or y}

.

The

l

=

0.

We

In particular,

fact that

\x

by

for simplicity, that the elite receive

they capture a fraction of

society in which the poor are unorganized).

between two values:

is

of the output (the rest gets destroyed or

fi t

though in the

elite,

a revolution

if

the capital stock in

i.e.

assume that

we have

/zis

Pr(// t

=

stochastic

h

fj,

)

—

(e.g.

it

a

and changes

q irrespective of

fluctuates captures the notion that

some periods

conducive to social unrest, and also that a promise to redistribute today

may

not materialize due to changes in circumstances tomorrow.

Finally, in each period the elite

it is

have to decide whether or not to extend the franchise.

extended, the economy becomes a democracy, and

sets the tax rate.

We

assume that

if

now the median

voter, a

If

poor agent

voting rights are extended, they cannot be rescinded.

So the economy always remains a democracy. 4

3

We think of time t <

as governed by a different model, for example with less inequality, so that there

for all t < 0.

redistribute by the elite, thus Tt — Tt =

This is not to deny that in many countries coups happen. It is nevertheless true that once voting rights

are extended and political parties are formed, it is relatively costly for any group to exclude the rest from

was no threat of revolution and no need to

4

the political process.

We

discuss

some reasons

for this in Section 5

The timing

of events within a period can

1.

the state

2.

the

elite

ji is

be summarized as

follows.

revealed.

decide whether or not to extend the franchise.

If

they decide not to extend

If

there

the franchise they also set the tax rate.

3.

the poor decide whether or not to initiate a revolution.

share the remaining output.

the tax rate

4.

there

the capital stock

(a

poor agent).

allocated between market

is

a revolution they

no revolution and the franchise has been extended,

is

by the median voter

set

is

If

is

and home production and incomes are

realized.

Analysis

2.2

The

analysis can be simplified by exploiting two features of the model. First, the capital

allocation decision takes a simple form.

capital to

home

best-response. It

attention to r£

Second,

use, thus

is

<

player. Also, all

0.

(

clear then that

H™ = H

f and

members

all

m =

if

t

,

If

If

r

t

> f = ^p,

then

on the other hand r

t

all

<

agents allocate their

f,then

H™ = H

no voter would ever choose r > f and we can

,

t

is

t

a

restrict

which reduces the number of actions to be considered.

of the elite have identical preferences, so

we can

poor agents have the same preferences, and when

not to participate in a revolution, there

is

no

"free-rider

it

treat

them

as one

comes to whether or

problem", because

if

an agent does

not take part in the revolution, he can be excluded from the resulting redistribution. So,

we can

treat all poor agents as one player. Therefore, this

a dynamic

game between two

In the text,

gies only

we

players, the elite

characterize the

non-Markovian equilibria

eral results.

The

Perfect Equilibria of this game, in which strate-

formally, let

a

(elite in

(fi,

explicitly

on time. Even though

natural in this setting, for completeness,

we

disciiss

Appendix, and show that they do not change our gen-

state of the system consists of the current opportunity for revolution,

represented by either

r

in the

is

as

and the masses.

depend on the current state of the world and not

the focus on Markovian equilibria

P=E

Markov

economy can be represented

l

\x

or

h

fi

,

and the

political state

P) be the actions taken by the

power) or

D

elite

(democracy or

when

the state

More

elite control).

is \x

=

pr or

1

p.

,

and

(democracy). This consists of a decision to extend the franchise

P = E, and a tax rate r when = (i.e. when franchise is not extended). Clearly,

= 0, P remains at E, and if = 1, P switches to D forever. Similarly, p (p, P\4>,T r

if

are the actions of the poor which consist of a decision to initiate a revolution, p (p — 1

representing a revolution), and possibly a tax rate rp when the political state is P — D.

4>

when

(j>

r

<f)

<r

)

These actions are conditioned on the current actions of the

elite

who move

before the poor

agents according to the timing of events above. Then, a (Markov Perfect) equilibrium

strategy combination,

each other for

We

priate

there

all \i

{a p

(fi,

P),a

r

r

(fi,P\(j),T )}

such that

Bellman equations. Let us

start

a revolution (starting in state

VP (R) —

never occur). Clearly,

and a are best-responses to

V P (R)

by defining

h

=

(X

fj,

xn-% which

is

this

game by

writing the appro-

we have

rich lose everything,

Next, suppose there

>

A

1/2)

V

(R)

=

the per-period return from revolution for

and wants

much

as

no allocative cost as long as r

<

lution, so in

=p

V>(pt, E)

we would have

((i

h

Vp

h

(/j,

,E)

a poor agent

t

as:

E).

is

balanced,

VP (D) =

The

h

(fi

T = (A — B)H. We

t

)H

Bhy

are in power

elite

and

\[tp*

=

and r

V

r

=

(D)

=

and there

=

0.

^jr-,

can then write

[^

)H

.

no threat of revo-

is

Therefore, the values of

,

= ,^,

(5 [(1

-

l

q)V'(fi

,

E). Suppose that the

.

The

+ gV V, E)\

E)

elite

play

revolution constraint

is

<fi

(1)

.

=

and r r

equivalent

=

to:

0.

Then,

V P (R) >

,E). In words, without any redistribution and franchise extension, the masses prefer

to initiate a revolution

Assumption

Revolution

is

1

g

more

when

That

this constraint binds.

fj,

= /A To make

the analysis interesting,

we assume

so that there

is

> $=£}.

attractive for the masses

sufficient

Assumption

when

1

wealth among the rich

ensures inequality

prefer revolution to the status

outcome

that

is:

inequality,

hT /hp

,

is

high so that they

have more to gain by taking control of the means of production, and when A

X)h r ).

=

Bhr+

{

r

f

are given by:

r,

= Ah? +

Finally, consider the state

Vp

,

ov

is

redistribution as possible, because redistribution has

any Markov Perfect Equilibrium,

poor and rich agents, j

median voter

.

1

(fj,

at the time of

f Therefore, the equilibrium tax rate will be r

the return to poor and rich agents

state

h

constant over time). Also, since the

is

In this case, the

and from the assumption that the budget

Now, consider the

\i

0.

a democracy.

is

if

since in the other state a revolution will

the revolution matters, hence the per-period return

T

poor agents

as the return to

the infinite future discounted to the present (note that only the value of

(since

a

and P.

can characterize the Markov Perfect Equilibria of

is

is

T

p

ct

for the elite,

is

(recall total

sufficiently

wealth of the rich

it.

is

low,

(1

—

high (and A low) that the poor

quo with no redistribution. Since the revolution

they will attempt to prevent

is

They can do

this in

is

two

the worst

different

ways.

0=1.

they can extend the franchise,

First,

V P (D).

under democracy,

Second, the

Then, the poor receive their return

can choose to maintain

elite

V

but redistribute through taxation: in this case, the poor obtain

With

the tax rate chosen by the rich.

either action

by the

elite,

political

h

p

(fj,

,E,T

the poor

=

power,

r

where r

)

may

T

0,

is

prefer

still

a revolution, thus:

V*(jm\ E)

Next,

we

= max {VP (R);

4>V P {D)

+

h

E, t

,

(fj.

t

)

=

(1

-

r

r )Ahp

+

t

t

AH + p [qVp

In words, the rich redistribute to the poor, taxing

—

therefore receive net income (1

next period we are

r T )Ahp from their

in state

still

=

\i

h

fi

the next period the economy switches to

V p (fi

l

>

}

.

)

,

all

E, r

T

)

income

own

+

- q)V p {fJ, E)]

(1

at the rate t t

capital

and

transfer

.

f,

r

<

f,

that

then each

is

(rich)

the

elite

(2)

The poor

T=

=

//',

redistribution stops

t t AH.

an

cannot tax themselves at a rate higher than f

all

in

commit

effective revolution threat.

agent would privately prefer to put

if

and the poor receive

,E). This captures the discussion in the introduction that the elite cannot

note that r

r

r

then redistribution continues. However,

,

//

h

(fj,

to future redistribution, unless the future also poses

if

0)^\ E, r

have:

Vp

If

-

(1

Also

= ^p;

their assets to the

home

sector, reducing aggregate tax revemies to zero.

Before proceeding further,

simplifies the exposition to restrict attention to the area of

it

the parameter space where democratization prevents a revolution, that

is

V P (D) > Vp (R).

Thus, we assume:

Assumption

Next,

Bhp + (A- B)H >

2

useful to calculate the

it is

extending the franchise,

utility is clearly

V p (fi

h

,

^f1

.

maximum

utility that

can be given to the poor without

E\q), as a function of the parameter

achieved by setting r r

=

f in

(2).

q.

This

maximum

Therefore, combining (1) and (2),

we

obtain:

0V,

Now,

is

if

Vp

m

h

(iJL

,

E\q)

=

W.

B, f )

< VP (R),

=

B* + (A

then the

-W-W -,X'- *><"-">

maximum

transfer that can

be made when

(3)

/j,

not sufficient to ensure that the poor receive enough to prevent a revolution.

clear that

?Y^)

<

Vp

h

(/j,

VP (R)

,E\q

=

1)

= VP (D) > VP {R)

by Assumption

1.

Moreover,

Vp

by Assumption

h

(/j.

,

E\q)

is

2,

and

Vp (fi h ,E\q =

=

h

\i

It is

0)

=

monotonically and continuously

,

increasing in

Therefore, there exists a unique q* G

q.

V

Finally, note that

This

(fi

,

E, r r )

because when there

is

in the

h

r

hand

is

E

of the elites, r

decreasing in r

is

=

a democracy, r

and

,

f in

=p

whenever p

(0,f]

r

such that

(0, 1)

=

but r

,

,

it is

1

(fj,'

,

= VP (R).

E\q*)

V

greater than

periods, whereas with the

all

h

rr

for all

Vp

when p

=

T

(D).

power

From

/J.

this

5

discussion the following characterization of equilibrium follows immediately:

Proposition

Suppose Assumptions

1

and 2

1

Then,

hold.

for all q

^

there exists a

q*,

unique Markov Perfect Equilibrium such that:

1.

If

< q\

q

then a r (fi ,E)

l

=

=

(cp

0),a r (p\ E)

=

(4>

=

<**

1,.)-

h

'(fi

,

E\<f>

=

= 0,t = f) and o*(jjl h D) = (r = f).

r

where f r G (0,f)

2. If ^ > g*, then a (p',£) = (0 = O,T = 0),a (p\ £) = (0 = 0,f

r

Also p (^,£;|0 = 0,t) = (p = 1) for all r < f

defined by 1/ p (#) = V p (p'\ £, f

=

0,r)

(p

=

a p (p'

1),

1

,

E\<f>

=

=

=

0,r

1, .)

(p

,

r

r

)

is

ap

r

ct

).

h

(fi

1, .)

,E\(f)

=

(

The

p

=

0,t)

= 0, r =

=

f)

(p

and

=

^(/A D) =

starts with the elite in power.

1

Now,

strategy of initiating a revolution

if

the franchise

>

(r

f

is

poor agent and sets the tax rate r

if

q

<

fi

=

h

fi

combination

,

in a

=

fi

.

=

fi

The poor play the optimal

ft

=

p',

when

>

q

q*,

the rich can prevent the

once again they set r

=

and

in the

the unique (Markov Perfect) equilibrium of the game.

even though the

is

elite face

may

this analysis:

a lower future tax burden with redistribution than

prefer to extend the franchise. This

is

because when q

<

q*,

not sufficient to prevent a revolution. With q low, the revolution threat

transitory, thus the

and then

when p

,

under democracy, they

is

game

they set a tax rate, f r just enough to discourage revolution. This strategy

is

redistribution

,E\(j)

p = p and the franchise has not been

the new democracy the median voter is a

In contrast,

p

p

h

There are three important conclusions to be drawn from

First,

(^

=

is

extended, in

f.

h

simple way: recall that the

then the rich set a zero tax rate

q*,

the state

=

the equilibrium path,

off

state switches to

if

cr v

= f).

revolution by redistributing. So in the state

state

and

,

can be expressed

and extend the franchise when the

And

r

0) for all

results of Proposition

extended.

,

r

poor realize that they

transfers will cease.

Redistribution

will only receive transfers for

when

noncredible promise of future redistribution by the

fj,

=

h

fi

elite.

a short while

can therefore be viewed as a

Unconvinced by

this promise,

5

When q ^ q* the equilibrium is no longer unique. In particular, there exists an equilibrium which

takes the form in part 1 of the Proposition, and one which is similar to part 2. Also, in the Appendix, we

,

allow for non-Markovian strategies and find that even

when

q

<

q*

,

there exist

with redistribution and no democratization, but there exists a cutoff q**

unique equilibrium has franchise extension in the state (/j, h ,E).

<

subgame

q* such that

perfect equilibria

when

q

<

q**, the

The

the masses would attempt a revolution.

revolution

only prevented by franchise

is

extension.

Second, perhaps paradoxically, a high value of q makes franchise extension

A

less likely.

high q corresponds to an economy in which the masses are well organized, so they

A

6

frequently pose a revolutionary threat.

case, democratization

is

more

However,

likely.

revolutionary threat, future redistributions

Germany, which had the most developed

may have been

naive intuition

this

is

become

that in this

not the case because with a frequent

This result

credible.

may

explain

why

socialist party, instituted the welfare state in

the nineteenth century without franchise extension, while Britain and Prance extended the

franchise.

We

Finally,

return to this issue in Section

4.

straightforward to see by comparing

it is

r

increasing in the extent of inequality, h /h p

V P (R)

and

A

3

Model

of

,

E\q*) that q*

more

The

role of inequality in

detail in the next section.

Growth and Inequality Dynamics

The Environment

3.1

The

previous section established

when they can use

why

the elite

may be

forced to extend the franchise, even

taxation and redistribution to reduce inequality.

We now

of the analysis to explore the implications of such political reform on growth

To

is

This implies that higher inequality enlarges

.

the area of the parameter space where democratization occurs.

franchise extension will be discussed in

Vp (fi h

simplify the analysis,

The same continuum

we

alter the focus

and

inequality.

consider a non-overlapping generations model with bequests.

of agents as in the last section

beget a single offspring. Technology

now

live for

only one period and each

identical to that in Section 2, but

is

human

capital

accumulates over time. This allows us to study how political transition interacts with the

dynamics of

inequality.

We assume that all agents have identical preferences defined over their own consumption

and "educational bequests" given

4+1 =

(cj,ej +1 =

ti'te,

u

for

i

—

period

r,p and 7 €

t,

and

l

e t+1 is

Alternatively,

v

would have t >

J

by:

(0, 1).

)

)

Here

(cj)

c\

"7

1

-7

(e\ +i

is

y

if

e\ +1

ife\+l

>

1

<\

the consumption of a

member

of group

i

alive in

the investment in the offspring's education. These preferences imply a

we could have assumed

0.

1

(ci)

l

fi

>

In this case, a high value of

so that even in this state with the elite in power,

l

fi

would

9

also lead to the

same

result.

we

constant savings rate equal to 7, and an indirect utility function which

Both the consumption and bequest decisions are made

as in the previous section.

end of the individual's

amount

of bequest,

The form

life.

=

e\ +l

income

linear in

is

a

minimum

amount, he

will leave

of the utility function implies that there

and when the agent cannot

1,

afford this

at the

is

nothing to his offspring. This non-convexity captures the feature that very poor agents will

not be able to accumulate assets (see Galor and Zeira, 1993).

The

human

offspring's

capital

given by:

is

=max{l;Zej + /}

^+1

where

Z>

and

1,

also

<

(5

The presence

indefinitely.

investment, there

The timing

is

a

1

which

will

(5)

guarantee that accumulation does not continue

of max{l;.} in (5) implies that even in the absence of any

minimum amount

of events within a period

of

human

now

would have.

capital that each agent

is:

1.

education bequests are received.

2.

the

3.

the poor decide whether to initiate a revolution.

decide whether or not to extend the franchise.

elite

there

If

is

a revolution they share

the remaining output of the economy. Otherwise, the political system decides the tax rate

a poor median voter

(i.e.

4.

the capital stock

if

there

democracy, and a rich agent

is

allocated between market

is

if

not).

and home production, and consumption

and bequest decisions are made.

Although the timing of events

Now, there

is

no

quite similar to Section

is

2,

there

is

a major difference.

possibility of choosing redistribution to prevent a revolution,

we

are set after the revolution decision within the period. This implies that

<

attention in the case of q

are focusing

terms of the analysis of the previous section.

Analysis

3.2

As noted above, the

and

q* in

because taxes

e\

+l

=

0,

if,

preferences in (4) imply a constant savings rate:

-)y\

<

1.

So

if

an agent can afford

he

it,

will

Assumption

The

agent

first

3

consume

7A <

1

all

of

it.

and {^B)

At

13

this stage

Z>

the

minimum

level of

when

we make the

7$,

his

income

if

7$ >

1

proportion

is

below a

following assumption:

1.

part implies that in the case where there

who has

=

will invest a fixed

of his post tax income in the education of his offspring, but

minimum, he

e\ +l

human

10

is

capital, h\

no taxation (rt

=

1, will

leave

=

T%

=

0),

an

no education to

his offspring, thus

=

h lt+l

accumulate while others do

accumulation of

is

B<

human

Therefore,

also.

1

The second

so.

capital takes place,

A, a steady state level of

human

possible for

is

it

some households not

when

part of the assumption guarantees that

and even

if

the rate of return on

than

capital greater

human

to

capital

can be reached. This second

1

part will not only enable accumulation by the rich in the absence of taxation, but also

ensure that taxation will never be severe enough to stop accumulation.

In

of our analysis,

all

we only

consider initial conditions such that:

hss

where h rss

>h

r

Q

>

(l

A

-l

)

human

the steady state value of the rich agents'

is

inequality ensures that

we

start with less than steady state

be growth (rather than decumulation of

human

The second

capital).

The

capital.

first

part of the

capital, thus there will

inequality ensures that rich

agents are beyond the point of non-convexity, and are able to leave positive educational

Once

bequests to their offspring.

different technology so that

first

no one accumulates and inequality

Autocracy and Only the Rich Accumulate

1:

control of the political system, rt

=

3 implies h%

Vt

1

>

0,

=

0.

<

as governed by a

stable.

=Z

T

h t+l

= Z (-yAhl)

(e[+1 )

human

.

Z>

1

by Assumption

Inequality in this

poor: yl/yt

=A

A

Case

2:

also

poor

still

r

t

_1

<

(7^)

capital

dynamics

for this

3,

= ((jAf Z)^

)

h\.

On

the

will also

Then we

rich

on the

group are given by:

and

A>

B, we have hss

>

way

to the steady state h\

i

is

1-

ratio of the rich to the

increasing, so inequality

income

in this

economy

is:

-i

Autocracy and All Agents Accumulate Suppose h rQ >

0.

The

(6)

Finally, the steady state level of aggregate

+ (1-A)(( 7 ^Z) T

=

then Assumption

.

economy can be measured by the income

= Ah\/A =

increasing too.

also that h%

elite in

This dynamic equation has a unique steady state:

h ss

Since ('fBy

Suppose

we have the

Since

so that the poor are unable to accumulate.

other hand will accumulate and the

loo

ss

is

t

analyze accumulation and inequality in the absence of the threat of revolution.

Case

is

of the periods

Equilibrium Dynamics without the Threat of Revolution

3.3

We

we think

again,

have: h{+1

= Z{^Ah\Y

be able to accumulate. Thus h\

>

converge to the same steady state, hss, given by

11

>

hp >

h$

(-fA)'

1

and

,

-1

for j

=

1 Vt.

This implies that both groups will

(6).

r and p. Since

(jA)

Since the poor start with less

,

the

human

capital

and converge

The steady

same

to the

income

state level of aggregate

Therefore, this

along this equilibrium path, inequality

level,

economy converges

more equal

to a

= A UjAf

Yg S

given by:

is

Zj

distribution of income

The reason

higher level of aggregate output than the previous case.

is

decreasing.

1_/

and

>

Yg S

.

also to a

for this is that in

Case

a fraction of the agents were unable to accumulate, causing a poverty trap.

1,

Case

Democracy We now

3:

We know

= f = ^=^-

consider the dynamics under democracy.

maximum

that in this case, the poor median voter will set the

tax rate: rt

.

Accumulation dynamics are then determined by:

= max jl, Z

h{+1

for j

T

ht >

=

1.

r

and

The second

p.

(7 [Bh{

(A -

+

part of Assumption

Z >

(jB)

3,

(7)

])^

ensures

1,

to accumulate

(7A)

-1

when they

Now

receive transfers.

may

so that the poor

If /iq

> (jA)'

1

/i[

+1

>

1

if

so that in the absence

,

would be able to accumulate, they

of redistributive taxation the poor

<

t

Therefore, taxation will not stop accumulation by the rich. This does not however

guarantee that the poor will be able to accumulate.

h,Q

B)H

consider the

be able

more involved case where

Suppose h p

not accumulate.

will also

=

1,

then equation

(7)

implies that the capital of the rich converges to the steady-state level:

D

h ss

It is

= 1Z

-

[{A{\

straightforward to see that hgS

A)

is

+ XB) h°s + (A-

strictly less

Condition

1

than Yg S and Yg S

7 [B

+ (A - B)

is

tax return

in this

/if

1;

thus Ygg

and

1

h\

A)

>

1

=

on

his

human

economy when

/if

=

accumulation by the poor.

level of

income (human

richer.

When

it is

capital,

1

and h

t

=A

X

hss-

+

(1

—

,

Let also Ygg

X)hg S which

=

hg S

If it holds, at

.

Condition

/i{j

some point the

=

1:

he receives an after

the total per-person transfer

is

1

necessary and sufficient for

is

rich will

have a high enough

capital) so that redistributive taxation will enable the

violated, there exists

no k[ < hg S that

to enable accumulation by the poor.

12

will

note that the term in square

this

and the second term

T

<

hgS the redistribution from taxation

the post tax income of a poor household with

B

.

consider:

- X)h§s +

=

=

poor to accumulate. To see

sufficient to enable the

brackets

Now

((1

This condition states that when

be

.

P

uniquely defined and hg S

denote the steady-state level of output when hp

is

B)X]

will

poor to grow

generate enough tax revenue

When

Condition

economy converges

holds, the

1

accumulating to hss, so inequality

when

hand,

to

Y$ s with both the poor and the

will also decrease as in the previous case.

the poor

do not accumulate, inequality,

given by

^

^

J to

J

'

'

% =

—

——

On

the other

—K—

\j-

(A-B)((l-A)/ir+A)+B

Vt

will increase despite the fact that there are also increased transfers to the poor. Also,

Condition

in

holds,

1

it is

also possible for the poor to start accumulating

which case inequality

this

will fall monotonically.

The necessary and

rich

from period

-,

'

when

t

=

0,

sufficient condition for

is:

p

7 [Bh

Condition 2

+

{A

which ensures that at time

than

(7) is greater

1,

- B)

t

=

thus 7^0

((1

0,

>

- X)h r + Xh p )} >

the after-tax income of the poor times the savings rate

We can now summarize equilibrium

be defined as

useful to notice that

1. It is

than Condition 2 because h

1 is less restrictive

1.

<

If h,Q

< hg S

whenever h^

<

1,

Condition

.

in (6):

controlled by the

is

T

dynamics without the threat of revolution. Let hss

Proposition 2 Suppose that Assumption

system

1,

(7/I)

-1

elite.

then h\

,

=

Then, we have r

t

1

>

V£

0,

E

3 holds, Hq

=

yA)~ l ,hss) and the

/

((

political

and:

h T monotonically converges to hss, aggregate

t

output converges to Yj 5 and inequality increases monotonically.

2.

> (jA)'

If h,Q

1

,

output converges to YgS

then both h\ and h r monotonically converge to h S s, aggregate

t

> Ys S and

inequality decreases monotonically.

Proposition 3 Suppose that Assumption

system

democratic.

is

1.

>

If /to

t

(jA)~ l

,

output converges to Y§s

2.

and

If

=

1

h,Q

Vi

>

4. If ho

i,

<

and h

/if

3. If

h\

ho

_1

(7^4)

r

such that h

and decreases

v

t

=

_1

1

> YgS and

inequality decreases monotonically.

and Condition 2

and Condition

holds, then inequality

1 fails

1

is

is

monotonically decreasing,

is

growing Vi

>

i.

Aggregate output converges to

no Kuznets curve: inequality

is

-

to hold, then inequality increases monotonically,

to

holds and Condition 2

Vi G (0,f), and h\

thereafter.

political

t

and h\ converges to h^s- Output converges

(7v4)

and the

hss),

,

f and;

There are a number of features to note.

there

-1

then both h v and h\ monotonically converge to h S s, aggregate

{^A)~ l and Condition

0,

<

h rQ G ((jA)

converge to hss, aggregate output converges to Yg S

t

<

=

Then we have r

3 holds,

First, in the

F55

fails

<

Y$g.

to hold, then there exists

Inequality

is

t

Y^.

absence of redistributive taxation,

always increasing or decreasing.

13

increasing until

A

Kuznets curve

is

however possible with a democracy (Proposition

sufficiently wealthy, the transfers

from them to the poor

But when the

inequality will increase.

become

rich

crucial threshold, the poor start accumulating,

redistributive taxation

Kuznets curve

Section

was

4,

is

key

when the

rich are not

not ensure accumulation, and

sufficiently wealthy, transfers reach

and inequality

Kuznets curve.

societies did not start out as

and there was no

will arise for a larger set of

franchise extension to an

more

for the

will

4):

falls.

However,

Thus

a

in this model,

this configuration of the

not totally compelling; as noted earlier and discussed in more detail in

Western

increasing,

is

Part

3,

democratic and were not so when inequality

redistributive taxation.

We will see that the Kuznets curve

parameter values when we add the possibility of revolution and

economy with the

elite in

we

power, and this

believe

is

a

much

plausible explanation for the Kuznets curve.

Second, inequality and especially the poverty of the masses are harmful to development.

When

the poor have h^

Y$ s whereas otherwise

,

Yg S

.

it

> (jA) -1

may

,

the economy converges to the higher steady state

get stuck in the lower steady state with per capita income

This relation between inequality and prosperity applies both to a democracy and an

autocracy.

This result

is

a direct consequence of the nonconvexity in the accumulation

technology as in Galor and Zeira (1993).

Finally, in this

lation

model democracy

is

good

for

economic performance

by the poor, but detrimental otherwise. In the absence

condemns the economy

much more

stringent.

On

enables accumu-

of democracy,

/iq

<

than Yg S

.

So the impact of democracy on performance

is

-1

,

the other hand,

if

democracy but the poor cannot accumulate, the economy converges to Yg S which

less

(jA)

Yg S but with democracy,

to the lower level of steady state output

the conditions for "stagnation" are

if it

there

is

is

even

ambiguous. With some of

the costs as emphasized by Alesina and Rodrik (1994) and Persson and Tabellini (1994),

democracy would have an ambiguous

effect

even when

enables the poor to accumulate.

it

Therefore, the empirical results that show no robust correlation between democracy and

growth should not be too surprising.

The Threat

3.4

We

will

now

of Revolution

analyze an economy which starts with the

constraint never becomes binding

of Proposition 2 will apply.

rich

If

(e.g.

if fi is

elite in

power.

If

the revolution

very small), then the equilibrium dynamics

on the other hand revolution becomes a

real threat, the

have to redistribute to the poor in order to prevent a revolution. However, given the

timing

we have assumed, a promise

to redistribute

14

by the

elite is

not credible, thus would

not prevent revolution.

power to the poor,

The only way

becomes binding, the franchise

is

when

general revolution constraint

Ah\ >

previous section:

when

AH /X.

t

to transfer political

is

the revolution constraint

extended and the dynamics of Proposition 2 are replaced

with those of Proposition 3 where the median voter

The

commitment

credible

extend the franchise. Therefore,

to

i.e.

make a

to

But now

a poor agent.

is

the rich are in power

constant and h Q /h^

fi is

same

is

the

is

changing over time.

r

as in the

Therefore, the revolution constraint becomes:

K < A(l-M)

^-Mi-A)When

revolution constraint are:

which

is

fairly intuitive.

benefit of the revolution

are fewer of

falls.

case, the

stuck at

1:

them with the same income

=

Condition 3

more

is

is less

2:

inequality

is

decreasing, so

Condition 4

inequality

is

it fails

The Threat

Condition 4

§

is

T

h

(i.e.

is

t

—

A)/i[)

given), the return

is

serious

(8); this is

when a

society has

because the

and when there

from revolution

more inequality

segmented (A relatively low).

When

Only The Rich Accumulate

In this

on the way with the poor

Thus we have:

Condition 3 holds, the threat of revolution

Case

the less tight

A,

> ^m=av

h ss

rich accumulate. If

the revolution constraint,

is

to Y§ s with increasing inequality

will never bind.

it

points to note about this

not binding at the point of steady state (which has maximal

If (8) is

1.

level

of Revolution

economy converges

/if

Two

the tighter

/z,

is

t.

to takeover the wealth of the rich ((1

is

The Threat

at time

is

Second, the higher

gap between h and h p ) and

inequality),

in

the higher

r

Case

If

first,

Therefore, the threat of revolution

(a larger

If

be no revolution

holds, there will

(8)

()

(8)

we can

to hold, then

of Revolution

it is

become

will

some point

as the

ignore the revolution constraint.

When

highest at time

effective at

t

All Agents

=

0.

Then we

Accumulate

In this case,

have:

< ^g=$.

satisfied,

then there

is

lower after this point, there

which both Conditions 3 and 4 hold

from the accumulation process,

themselves by force.

If in

at

no revolutionary threat

at

time

is

never any threat of revolution.

is

of interest. In this case,

some point they

will

if

t

=

and

since

The configuration

the poor are excluded

want to redistribute resources to

contrast they are also accumulating along the development path,

they will not see revolution as a worthwhile activity.

15

As discussed above, when the

revolution constraint binds, the elite have no choice

but to extend the franchise. However, we have to ensure that the extension of the fran-

The necessary condition

chise generates sufficient redistribution to stave off a revolution.

Assumption

for this is related to

—

X)h1

+ A/if] /A. The LHS

and the

RHS

is

Afi

[(1

what he

(A

2 in Section 2.

what a poor agent

is

We

gets with revolution.

- B)

((1

(8) implies

that h

T

t

=

A (A - /z) >

are particularly interested in whether

and the poor are not

we combine the

In this sxibsection,

Then the

critical

From

1

at t

Growth and Democratization

Throughout we assume that the

following result

Suppose the economy

—

starts in

is

Case

1,

elite start in

and Conditions

)

~v,

,

/i(l-A)'

the revolution constraint binds and the

on the poor also start to accumulate, inequality

converges to YgS

and outline

power

immediate from our previous analysis:

the rich accumulate and the poor do not. At

threshold

this point

to impose:

holds.

The Kuznets Curve The

Result

we need

analysis of the previous two subsections

possible paths of development.

and Assumption 3

ac-

- //).

Results: Implications For

3.5

some

B{\

+ A/if) + Bh\ >

S[Z\) at this point. So to ensure that in this

case franchise extension prevents a revolution,

Condition5

X)h\

gets after redistributive taxation,

this condition holds at the point the revolution constraint binds

cumulating. Equation

-

t

1,

3

and

5 hold.

inequality exceeds the

elite

falls

extend the franchise.

and aggregate output

.

In our view, this sequence of events corresponds to the experience of Britain, France,

Sweden and Germany, where,

as discussed in

more

detail in the next section, after a pe-

riod of increased inequality accompanied by wars and depressions, the threat of revolution

intensified.

This forced the extension of the franchise and increased redistribution. As a

result, inequality declined.

section,

we

This case

is

the main focus of our analysis. In the rest of this

outline alternative paths of development to contrast with the Kuznets curve.

Autocratic Disaster

Result 2 Suppose the economy

starts in

the rich start to accumulate at time

t

=

Case

1,

and Condition 3 does not hold. Then,

and the poor do

not.

The

revolution constraint

never binds, the economy remains an autocracy with high inequality and converges to

aggregate output Yg S

.

16

This

the path of an economy where

is

initial inequality is high,

but nonetheless, the

masses do not pose a revolutionary threat. This might be because the absence of a welldeveloped

other factors imply that

civil society or

/j,

is

small (that

hard time organizing, therefore a revolution would be very costly

r

high so that revolution

became a

not as beneficial at given h /h p

is

real threat, this

economy could democratize,

If \i

for

the poor will have a

them), or because A

is

were large so that revolution

redistribute to the poor,

and reach

Thus, contrary to conventional wisdom, political and social

a higher level of income.

instability

.

is,

may sometimes be good

for growth.

In particular, whether a

good "revolution

technology" hinders or enhances growth depends on which case the economy

is in.

East Asian Miracle

Result 3 Suppose the economy

accumulate starting at time

t

=

0,

starts in

Case 2 and Condition 4 holds. Then,

inequality declines

binds. Aggregate output converges to

Yg S

all

agents

and the revolution constraint never

.

In this case, along the development path the poor segments of the society are sharing

in the benefits of rising average per capita income,

to create social unrest.

and therefore do not

find

it

This case reminds us of Taiwan and South Korea.

worthwhile

In the early

post war period, both of these countries were in a situation very similar to that of the

Philippines except that inequality was

autocratic disaster).

elite,

7

In

much

three, political

all

higher in the latter (as in the case of the

power was concentrated in the hands of an

not unlike nineteenth century Britain. In Britain per capita income and inequality

grew and

political transition

took place. In the Philippines, aggregate income stagnated at

a high level of inequality, and there was no political transition. In contrast to these cases,

Taiwan and South Korea experienced

fast

somewhat. 9 Our model suggest that

fell

7

The Gini

coefficient

was 0.34

in 1965 in

growth but no democratization, 8 and inequality

this

may have been

because the gains of growth

South Korea and 0.31 in 1964

in

Taiwan whereas

it

was 0.45

in Philippines in 1957 (see Fields, 1995).

8

A

process of democratization

is

now

occurring rather rapidly in the Philippines, South Korea and

Taiwan. Nevertheless, for the purposes of the present study it is interesting to understand the prolonged

undemocratic regimes in these countries as opposed to the experiences of much faster democratization

in Britain and other developing countries such as India, Colombia and Turkey. It is also significant to

note, for example, that in the thirty years prior to

its

democratization, 1960-90, per-capita

GDP

in

Korea

increased by a factor of 6.89. This was considerably faster than British growth during the nineteenth

century. During the period 1820-1870, British income per-capita increased by a factor of 2.75 (all data

from Maddison, 1995). This motivates our claim that South Korea and Taiwan have experienced a period

of very rapid growth, but no democratization and no Kuznets curve. Section 5 discusses how a simple

extension of our model can account for delayed, rather than no, democratization in South Korea and

Taiwan.

9

for

For example, the average Gini coefficient over the period 1965-1970 was 0.34 for South Korea and 0.32

Taiwan, and these averages fell to 0.33 and 0.30 respectively for the period 1981-1990, see Campos and

17

were equally divided between different social classes in South Korea and Taiwan, so the

poor did not organize and the

until

much

did not have to extend political power to wider groups

elite

later (see also the discussion in Rodrik, 1994;

and Campos and Root, 1996;

in

support of such a view).

Revolution

Result 4 Suppose we are

Case

1,

the rich start to accumulate at time

t

binds at time i

The main

when

>

h^

in

:^~^

,

is

=

The

revolution threat

is

that

B

is

large relative to A.

only a limited ability to tax the rich in a democracy, and

place along the equilibrium path.

to

not.

place.

from the Kuznets curve

profitable for the masses to take over the

social unrest increased,

and the poor do

and a revolution takes

difference of this case

This implies that there

Condition 3 holds but Condition 5 does not. Then

means

This case

and attempts

is

to bring

it is

more

of production. Thus, a revolution will take

similar to pre-revolutionary Russia

more moderate groups, such

where

as Mensheviks,

power were unsuccessful.

Historical Perspective

4

Our theory

is

motivated by historical evidence. Here we

will

provide an overview, empha-

sizing the evidence in support of the following four features:

1.

Inequality was increasing before, and decreasing after, the extension of the franchise.

2.

The

as a strategic

3.

power before the franchise and extended the franchise

elite controlled political

move

to avoid a revolution or at least very costly political unrest.

Democratization was directly (redistribution) or indirectly (expanded education) a

key factor in the reduction in inequality.

4.

There are differences

in social conditions

which make some periods more conducive

to social unrest, and there are also differences in the level of organization of the masses

across countries which are important in determining political outcomes.

Our most

Germany

4.1

detailed evidence

is

from Britain, but evidence from Prance, Sweden and

also supports our model.

Inequality

Britain Data on income inequality

for the nineteenth

century are not extremely reliable.

However, a number of studies using different data sources on Britain reach the same conRoot (1996), Table

1.1.

18

elusion.

Inequality increased substantially during the

then started falling in the second

This picture

1870.

is

1

to

be sometime

is

and

after

of Lindert

not completely uncontroversial (see Feinstein, 1988).

taken from Williamson's (1985) Table 4.2 gives a representative picture:

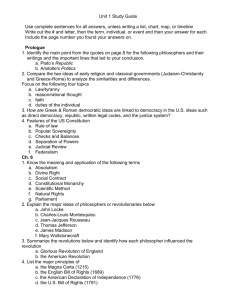

Table

1

-

British

Income Inequality

Share of the Top 10%

Gini Coefficient

47.51

0.400

1830

49.95

0.451

1871

62.29

0.627

1891

57.50

0.550

1901

47.41

0.443

1911

36.43

0.328

1915

36.46

0.333

1823

A

The turning point appears

also consistent with the findings of Crafts (1989),

(1986) on wealth inequality, but

Table

half.

half of the nineteenth century,

first

similar pattern also emerges from earnings inequality data reported in Williamson

(1985) Table 3.2 where the Gini coefficient increases from 0.293 in 1827 to 0.358 in 1851

and

falls to

0.331 in 1901.

Other Countries While

tive survey, argues that

In

Germany

again the data are sparse, Morrisson (1997) in his authorita-

Germany, France and Sweden

inequality rose during the nineteenth century

peak around 1900. For example, Kuznets (1963)

per cent went from

declining to

31%

28%

in 1873-1880 to

in 1911-13.

1880, rising to 32.6% in 1900

inequality

all

fell

Dumke

and

rapidly during the

the income share of the top

the Kuznets curve in

32%

went through a Kuznets curve.

and most researchers place the

finds that the

in 1891-1900, stayed at

(1991) finds the

falling to 30.6

%

fallen

Germany peaked

32%

during 1901-1910,

same income share

to be

in 1913. Following the First

Weimar Republic. Kraus

5% had

income share of the top 5

28.4%

in

World War

(1981) records that

by 1926

by 6.2%. Overall, Morrisson (1997) argues that

in 1900,

went

flat

and started

to fall in the 1920's.

For France, Morrisson (1991, 1997) argues that inequality rose until 1870, with the income

share of the top 10 percent peaking at around 50%. However, inequality started to

the 1870's, and in 1890 the income share of the top 10 percent was

falling to

grew

in

36% by

1929.

Finally,

down

to

fall in

45%, further

Soderberg (1987, 1991) records that income inequality

Sweden, peaking just before the First World War,

during the 1920's and then falling rapidly thereafter.

19

levelling off or falling slightly

Franchise Extension and the Threat of Revolution

4.2

Britain In Britain, the franchise was extended

(and later in 1919 and 1928 when

women were

in 1832,

finally

and then again

allowed to vote).

in

1867 and 1884

When

introducing

the electoral reform to the British parliament in 1831, the prime minister Earl Grey said

"There

than

is

am

no-one more decided against annual parliaments, universal suffrage and the ballot,

The

I...

Principal of

my

reform

reforming to preserve, not to overthrow."

reform

is

is

to prevent the necessity of revolution... I

am

(quoted in Evans, 1983). This view of political

shared by modern historians such as Briggs (1959) and Lee (1994). For instance,

Darvall (1934) writes: "the major change of the

was the reform

of Parliament

Whigs. ..as a measure to stave

first

three decades of the nineteenth century

by the 1832 Reform Act, and

off

this

was introduced by the

any further threat of revolution by extending the franchise

to the middle classes." In fact, the years preceding the electoral reform

by unprecedented

political unrest including the

were characterized

Luddite Riots from 1811-1816, the Spa

Fields Riots of 1816, the Peterloo Massacre in 1819,

and the Swing Riots

of 1830 (see

Stevenson, 1979, for an overview).

The reforms

that extended political power from a narrow elite to larger sections of the

society were immediately viewed as a success not because of

or democracy, but because the threat of revolution

Lee, 1994).

some

ideal of enlightenment

and further unrest were avoided

(see

Before the 1832 Reform Act, the total electorate stood at 478,000 out of a

population of 24 million. Although the Act reduced the property and wealth restrictions

on voting and increased the electorate to 813,000, the majority of British people could not

vote. Moreover, the elite

contained

less

still

had considerable scope

for

patronage since 123 constituencies

than 1,000 voters (the so-called "rotten-boroughs"), and there

of serious corruption

and intimidation

of voters

which was not halted

is

evidence

in Britain until the

Ballot Act of 1872 and the Corrupt and Illegal Practices Act of 1883 which introduced

effective secret ballots at elections.

The

process of increased representation gained

momentum

with the Chartist movement

during the 1830's and 1840's. Consistent with our approach, leading chartists saw increased

way

representation as the only

growth

(see Briggs,

1959).

movement was again one

to guarantee a

more equitable distribution

of the gains of

In the meantime, the response of the elite to the Chartist

of preventing further unrest.

For example, during the 1850's

Lord John Russell made several attempts to introduce franchise reform arguing that

it

was

necessary to extend the franchise to the upper levels of the working classes as a means of

preventing the revival of political radicalism (Lee, 1994). In discussing the lead up to the

20

1867 Reform Act, Lee argues that "as with the

first

Reform Act, the threat

has been seen as a significant factor in forcing the pace; history was repeating

interpretation

is

supported by

many

of violence

itself."

This

other historians, for example Trevelyan (1937) and

Cowling (1967). The Act was preceded by the founding of the National Reform Union

in

1864 and the Reform League in 1865 and the Hyde Park riots of July 1866 provided the most

immediate catalyst

(see Harrison, 1965).

As a

result of these reforms, the total electorate

was expanded from

1.4 million to 2.52 million

and then doubled again by the Reform Act

of 1884

and the Redistribution Act

of 1885

removed many remaining

inequalities in the

distribution of seats (see Wright, 1970). Overall, in Britain the timing of franchise extension

corresponds quite closely to the peak of the Kuznets curve.

Other Countries

Weimar Republic

In Germany, democracy was established with the creation of the

in 1919.

There

is

no controversy amongst historians that

the threat of social disorder and conflict following the defeat in the

1943;

Abraham,

1986).

IV

coalition of "iron

rural areas

flat

and

to

Gerschenkron,

of Prussia