CUNY Task Force on Retention Judith Summerfield

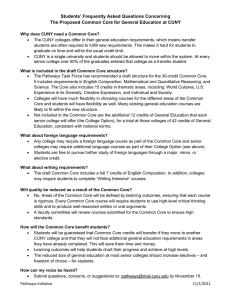

advertisement