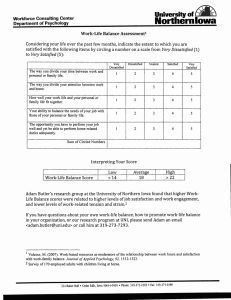

W L C ORK AND

advertisement