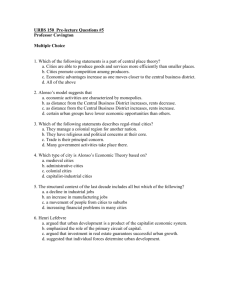

By SUBMITTED IN AT

advertisement