2 Sunday in Lent March 1, 2015 10 AM & 12 Noon Liturgies

advertisement

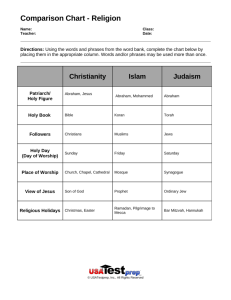

2nd Sunday in Lent March 1, 2015 10 AM & 12 Noon Liturgies J.A. Loftus, S.J. About a dozen years ago an enigmatic and somewhat controversial Anglican Bishop, John Shelby Spong, wrote a book called The Sins of Scripture: Exposing the Bible’s Texts of Hate to Reveal the God of Love. As you might imagine, Bishop Spong had a field day with our first reading, often called simply the sacrifice of Isaac. Calling this reading a “text of hate” might seem a bit strong to you, but then again, perhaps not. It certainly is a text that calls for very careful interpretation. There is a lot at stake here. Violence in the name of God is, unfortunately, enjoying resurgence in the 21st century. And children are, oddly enough, still a preferred target in many places. The violence in the book of Genesis has, in fact, been repeated frequently by all three great monotheistic religions. That includes us! God’s “testing” of Abraham is a revered story in Christianity, Islam, and Judaism. That’s more than three billion people who all share this story in common. I repeat: this is a crucial text to get right. Lives depend on it. Do we really believe in this “testing” god? What kind of a god would ask such a thing? I have tried several times in preaching on this text to conjure a verbal description of a Caravaggio painting that hangs in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. It captures the horrifying violence of this scene graphically. Abraham is holding his son down on the ground by his neck. Isaac’s mouth is open and he seems to be crying in astonishment. Abraham just looks away with an agonized and perplexed gaze. And then there is a half-naked angel pulling Abraham’s arm back. It is a terrifying image. It was then, and still is today. For me, it is even more painful today as we hear of almost nightly beheadings taking place in that same geographical part of our world. Can a god really be that cruel and sadistic? To some, the answer seems to be yes. And that’s frightening! Another Anglican Bishop, N.T. Wright, suggests why this is all so scary. He says: “One of the primary laws of human life is that you become like what you worship; what’s more, you reflect what you worship not only to the object itself but also outward to the world around” (Surprised by 2 Hope: Rethinking Heaven, the Resurrection, and the Mission of the Church). So Genesis has to be dealt with somehow. The issue becomes are there ways around this violent face of god? There are. Let me suggest three. The first is exegetical, i.e. from a careful study of the text itself. Here one realizes that there are actually two gods named, two different faces of god. The god who asks for Abraham’s sacrifice is called Elohim. That is an ancient name for a Jewish god, but it is also the name given to all the pagan gods, the “false” gods of the heathen. The God who stops the sacrifice is called Yahweh, the distinctive Hebrew name for God that the Jewish people use to this day, and never say or write. Not an accident, most likely: two different faces of God, one stopping the violence. The second way of interpretation is anthropological and cultural. The very influential French anthropologist and theologian Rene Girard and his followers pick up this theme. They realize that at this juncture in human history there is an epochchanging shift taking place. Human sacrifice, long a mainstay of religious worship, was becoming intolerable. 3 However else one interprets this sacrifice story, it is also about the end of human sacrifice to any gods. The most significant moment in the story is (in this view) when Abraham substitutes a ram for his son, and does it in the name of the “real” God. The face of this God actually helps shift human history away from violence in any form. That’s why the story is told. The third interpretation just takes us on a journey with that “real” God. And the journey takes us directly to today’s gospel passage. For here, high on a mountaintop, God shows God’s face directly to human beings. The person of Jesus from Nazareth is “morphed” (the Greek word for transfigured really is metamorphase) before their very eyes into the face of God. And that face is human! This is the “real” God before their very eyes. And then the voice of the real God: “This man—this human being just like yourselves in all things—is my Beloved! Listen to him! Watch him! Learn from him!” He is here to end all violence once and for all. The face of God, it seems, was all along human. And the face of God remains so—even today. The face of God that they saw on that mountaintop is here as well. Just look around. It is forever us! 4 It is in us! It is us! The body of Jesus reveals in that moment not just who he was and is and will become. He reveals what we were, are, and will become as well. There are no texts of hate to be found here. So Peace be with you! 5