C21 Resources T A “catholic” Intellectual Tradition

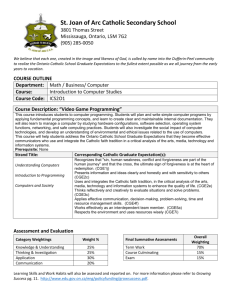

advertisement