I Pi HI' ^9Nv

advertisement

MIT LIBRAHIES

:

Hi

3 9080 01917 6608

^9Nv

i

tmm

fWffli!

Pi

Mlll/lwfflltltllh

i^

tHummUlllit

;.

HI'

I

"lift

'.;

'

Digitized by the Internet Archive

in

2011 with funding from

Boston Library Consortium

Member

Libraries

http://www.archive.org/details/evolvingstandardOOelli

HB31

.M415

DEWEY

13

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Department of Economics

Working Paper Series

EVOLVING STANDARDS FOR ACADEMIC PUBLISHING:

A q-r THEORY

Glenn

Ellison, Massachusetts Institute

of Technology

Working Paper 00-13

July

2000

Room E52-251

50 Memorial Drive

Cambridge, MA 02142

downloaded without charge from the

Social Science Research Network Paper Collection at

http //papers ssrn com/paper taf?abstract_id=XXXXXX

This paper can be

:

.

.

.

MASSACHLISETTSTfJSTiTUTr

TECHNOLOGY

LIBRARIES

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Department of Economics

Working Paper Series

EVOLVING STANDARDS FOR ACADEMIC PUBLISHING:

A q-r THEORY

Glenn

Ellison, Massachusetts Institute of

Technology

Working Paper 00-1

July 2000

Room E52-251

50 Memorial Drive

Cambridge, MA 02142

downloaded without charge from the

Social Science Research Network Paper Collection at

http://papers.ssrn. com/paper. taf?abstract_id=XXXXXX

This paper can be

Evolving Standards for Academic Publishing:

Glenn Ellison

A

q-r

Theory

1

Department of Economics

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

.-v

June 2000

would like to thank the National Science Foundation (SBR-9818534), the Sloan Foundation

and the Center for Advanced Studies in the Behavioral Sciences for their support. I would like

to thank Robert Barro, John Cochrane, Ken Corts, Drew Fudcnberg, John Geanakoplos, Robin

Pcmantlc, Gary Saxonhonsc and various seminar audiences for helpful comments and Christine

Kiang and Nada Mora for outstanding research assistance.

J

I

Abstract

This paper develops a model of evolving standards

for

academic publishing.

It is

mo-

tivated by the increasing tendency of academic journals to require multiple revisions of

articles

and by changes

in

quality dimensions: q and

the content of articles. Papers are modeled as varying along two

r.

The former

represents the clarity and importance of a paper's

and polish. Observed trends are regarded as

increases in r-quality A static equilibrium model in which an arbitrary social norm determines how q and r are weighted is developed and used to discuss comparative statics

explanations for increases in r. The paper then analyzes a learning model in which referees

(who have a biased view of the importance of their own work) try to learn the social norm

main ideas and the

latter its craftsmanship

from observing how their own papers arc treated and the decisions editors make on papers

they referee.

The model

predicts that social

increasingly emphasize r-quality.

JEL

Classification No.: A14, D70,

C73

Glenn Ellison

Department of Economics

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

50 Memorial Drive

Cambridge,

MA

02142-1347

norms

will

gradually but steadily evolve to

Introduction

1

I

encourage potential readers of this paper to

first

put

it

down

for

through a thirty- or forty-year-old issue of an economics journal.

convey much better than

much

longer.

1

2

longer introductions.

They have

have more sections discussing extensions of the main

The

anticipate that this will

I

can how dramatically economics papers have changed over the

I

few decades. Papers today are

last

two minutes and thumb

results.

They have more

They

references.

Around 1960

process by which papers get published has also changed dramatically.

the Quarterly Journal of Economics reserved the "revise-and-resubmit" option for five or

so special cases per year.

submit

their papers,

about nine months.

takes 20 to 30

receive reports,

Today extensive

months

similar experiences.

they have received

at

I

and get a

final

norm and

in

let

still

authors

acceptance within

getting an acceptance

disciplines

have had

academic journals arc widespread and dramatic,

field

this reflects that the

changes have occurred

see only a small part of the overall picture.

develop a model to organize the observed trends and help us think about

potential explanations.

as differing along

revisions

revisions arc the

Perhaps

attention.

gradually and that researchers in each

In this paper

make

most top journals. 4 Many other academic

While the changes

little

most journals' processes

In the early 1970's

My

central premise

is

that

two quality dimensions: q and

r.

we can

I

academic papers

usefully regard

think of q as reflecting a paper's

main

ideas and r as representing other aspects of quality described by words like craftsmanship,

thoroughness and polish.

phenomenon

of a single

I

think of the various changes noted above as different aspects

— an increase

in the r-quality of published papers.

an equilibrium model of time allocation and quality standards and use

'Ariel Rubinstein's 1982

is

Econometrica

article, "Perfect

shorter than the average note in Econometrica in 2000

For example,

Amartya Sen's "The

Equilibrium

(if

in

it

I

first

develop

to discuss

what

a Bargaining Model," for example,

one accounts

for the

type

sizes).

Impossibility of a Paretian Liberal" and two other papers in the

January- February 1970 issue of the Journal of Political Economy had one paragraph introductions. No

introduction in the Feburary 2000 JPE was shorter than seven paragraphs and two were longer than Sen's

entire paper.

An extreme example here is Michael Spence's 1973 QJE paper "Job Market Signaling." It contains two

While my anectodes all relate to classic papers, old journals also contain many derivative papers

references.

making

N

'

oider contributions to long forgotten literatures. These also look very different from today's

papers.

''The one exception is the QJE where

on the duration of review process.

it

takes about 13 months. See Ellison (2000) for

much more data

might cause such an increase.

I

then develop a dynamic learning model

in

which economists

struggle to reconcile the high standards to which they arc being held with the mediocrity

they see

of their

(This occurs in part because economists have biased views of the quality

in journals

own

The model

work.)

predicts that social

norms

will

evolve gradually to emphasize

r-quality.

I

begin in Section 2 with a quick look at some data on the form of papers and the length

of the review

and revision process

in a

number

of disciplines.

Section 3 describes a static equilibrium model of the journal publishing process.

continuum of economists are endowed with one unit of time

in

which to write one paper

A

for

the one journal in the profession. Papers are described by their position along two quality

dimensions, q and

of the

main

r.

interpret the q dimension as reflecting the clarity

I

results of the paper,

and the

dimension as reflecting various other aspects

r

that are typically improved

of quality (generality, robustness checks, extensions, etc.)

and when authors "polish" papers prior to submission.

in revisions

economists make

on

r-quality.

how

is

to divide their time

A commonly

and importance

The main

decision

between the developing new ideas and working

understood social norm determines how the quality dimensions

arc weighted.

I

analyze the static model in Section

produces a reasonable outcome. Papers

4.

For a range of parameter values the model

initially

submitted to the journal can be divided

into three groups. Papers with the lowest q are determined to be of sufficiently low interest

that no feasible revision could

papers with intermediate

possible, but only

make them

q's are

acceptable.

if

Finally,

make two main observations about

are possible.

spend most of

spend very

If

the

their

little

A

second set of

papers with a sufficiently high q

they achieve a somewhat lower

always able to meet the revision standard that

I

are not revised.

marginal. These papers are revised to the greatest extent

some become acceptable.

be publishable even

They

is

r.

set for

The authors

of these papers are

them.

the static model. First, a continuum of social

community agrees that

^-quality

time developing main ideas.

If

is

will

norms

very important, then authors will

r-quality

is

very important, then authors

time on ideas and focus on revisions. Nothing in the model prevents either

extreme or something

in the

middle from being an equilibrium. Second, the marginal papers

that

fall

just short of being accepted arc relatively low in (-/-quality

/•-quality relative to the set of

that a paper's q-quality

The model makes

is

resubmitted papers. This

developed

and revisions

first

number

clear that a

is

and

a consequence of the assumption

later increase r.

of equilibrium comparative statics explanations

could be given for increases in r-quality. Such explanations, however,

in practice.

them

The observed changes

economics and other

in

requires cither a large change in

outcome

My

to an exogenous variable.

relatively high in

some exogenous

fields

may

not work well

are large. Accounting for

variable or a high sensitivity of the

impression from the empirical work I've done

the economics profession has not changed

much

is

that

over the last thirty years. (Ellison, 2000)

Equilibrium explanations arc also hard to reconcile with editors' comments that changes

were not planned or desired.

explanations

— to account

I

for

take these difficulties as motivation for exploring evolutionary

observed changes such an explanation only need sto provide

a good reason to think that each year papers

be a paragraph longer and require a

will

couple weeks more to revise than the year before.

Section 5 describes a dynamic learning model.

journal's referees

(who arc

also the authors).

The main

The

actors in the

model arc the

referees are not self-interested.

They

simply try to apply the prevailing standards of the profession in weighting 7-quality and

r-quality and in proposing a set of

improvements that would bring a paper up to the pub-

lication threshold. Referees learn the prevailing standards

of

what

revisions they arc asked to

from two sources: observations

make and observations

of

whether editors eventually

decide to accept or reject papers they have refereed. Editors are not an active force in the

model. They simply

fill

the journal's slots by accepting the fraction r of papers with the

highest average quality (weighted according to the then prevailing

model of a busy

editor.

Making

referees the driving force

comments that they abhor the trend toward

fifty

is

norm).T view

this as

a

also consistent with editors'

page papers with myriad extensions and

wish that authors would just concisely explain what ideas they have.

Section 6 discusses the dynamic model with no overconfidence bias. All of the equilibria

(if

the static model are steady-states.

standard that

is

I

note that

if

infeasibly high, then economists will

referees try to to hold authors to a

both realize that overall quality stan-

dards arc lower than they had thought and conclude that r-quality must be relatively more

important than they had thought. The latter inference

is

papers that are unexpectedly accepted are relatively low

made because

in q

and

the submarginal

relatively high in

r.

Section 7 adds in the assumption that economists are biased and think their work

than

slightly better

it

really

is.

5

The former

steady-states of the model are destabilized

as referees try to hold others to the higher standard that they perceive

to their

own

papers.

Standards can not stray

is

being applied

from the equilibrium set

far

- -

referees

would see editors accepting many papers they strongly recommended against and

would overwhelm the

What happens

e bias.

authors to a standard that

instead

is

about how economists rationalize standards that are too high

still

gradual evolution of social norms to increasingly weight r-quality.

them a candidate

the dynamics makes

for

is

good enough

There has been

notable

is

little

to

make

its

all,

tastes.

The

focus

model

is

The

result

is

The slow steady form

a

of

because the dynamics change once

work on the dynamics of standards. The most

in

which a

admission to a club. (One could think of publishing

have heterogeneous

applies.

acceptance a sure thing.

related theoretical

Sobel's (1998) analysis of a

of the previous section

explaining observed trends. In the long run the

process stops short of papers having no q-quality at

no paper's idea

this

that referees perpetually try to hold

The observation

slighly too high.

is

is

on how

series of

in

candidates work to obtain

a journal as an example.) Judges

different voting rules lead to rising, falling

or fluctuating standards.

The

general

fact that

title

I

have not to followed the current trend and given this paper an overly

and a seven page introduction should not be taken to indicate that there are not

broader lessons to be learned from

for politeness,

standards

for

it.

There are

all

kinds of social norms,

language and violence on television, hazing at

hours worked by young doctors and lawyers, years spent

of grades, etc.

Many

of these

e.g.

in

standards

fraternities,

higher education, distributions

norms have commonly perceived

trends, but other than the

In the psychology literature this is referred to as an overconfidence bias. An often discussed example is

Svenson's (1981) finding that about 90 percent of the U.S. college students in his study estimated themselves

to be safer (and more skillful) at driving than the median subject. Psychologists have reported that experts

many fields are overconfident in assessing their own ability to answer questions. Lichtenstein, Fischoff

and Phillips (1982) piovide a nice (but early) survey. Overconfidence is frequently mentioned in finance to

motivate the existence of agency problems and to justify the actions of noise traders as in De Long et al

in

(1990). Odean (1998) is a notable recent contribution with a detailed summary of psychology and finance

papers on overconfidence. Rabin (1998) discusses a number of other psychological biases and their relevance

to economics.

literature on fashion cycles, e.g.

Kami and

of the existing literature on social

Schmeidlcr (1990) and Pesendorfcr (1995), most

norms doesn't focus on change.

conclusions about other norms from

my

My

results.

view

should be expected and

On

a theoretical

level,

if

so in

what

will

not try to draw

that one would need to analyze

is

each application separately and think about how the norm

drift

I

is

learned to assess whether a

direction.

the paper's innovation

to note that

is

one can produce a model

that explains a long gradual trend by making a slight perturbation to a model with a

continuum of

equilibria.

penetrating question:

In an early presentation of this paper

'so arc

you trying to

tell

us that you're going to explain a thirty-year

trend by saying that we've been out of equilibrium the whole time?'

hope to convince readers that models of the type

Some data from

2

Table

1

The

table

lists

long as they were twenty

long

how

"Yes!"

I

possible.

the form of an academic article has

number

five

many

years ago and have about twice; as

of references for

now than

in 1975.

The

references. Jn almost

increases are

Likewise with the exceptions of law and history, articles

references.

way

is

make such arguments

the average page length and the average

papers seem to be longer

the sciences.

more

answer

top journals in a number of disciplines. Economics papers arc roughly twice as

articles in

all fields

introduce

I

My

various disciplines

provides some statistical evidence on

changed.

Robert Barro asked a

more moderate

now tend

While economics has experienced substantial reference growth

to go to catch

many

in

to have

it

has a

social sciences.

Table 2 provides some evidence on how long

extensively they are revised for publication in a

takes longer to get a paper accepted

now than

it

takes to review papers and on

number

it

of fields.

did in 1975.

how

In almost every case

it

While Econometrica and

the Review of Economic Studies have the most drawn out publication processes

among

the listed journals, similar trends are visible in computer science, psychology, statistics,

linguistics

and

finance,

and

I've

been told that

many rounds

at the top journals in marketing, political science,

A

slowdown

is

also visible in

some

sciences, but the

of revisions are also the

and a number of other

time scale

is

norm

social sciences

completely different.

The

3

model

static

In this section

describe

I

a.

simple static model of academic publishing.

The main

the model are a continuum of economists (of unit mass). Each economist

one unit of time and

may

mass r of papers with

and

leisure time,

i.e.

write one paper. There

<

r

<

is

is

endowed with

one economics journal that publishes a

Economists preferences arc lexicographic

1.

actors in

in publications

they attempt to maximize the probability of publishing an article in

the journal; holding the probability of publication fixed they prefer more leisure to

Papers can be

dimension

is

fully described

by two dimensions of

quality, q

and

The

r.

less.

g-quality

intended to reflect the inherent importance, interest, clarity etc. of the main

ideas of the paper.

The

r-quality dimension

when they

quality that authors improve

paper's exposition, to

make

is

intended to

aspects of

reflect additional

arc asked in revisions to improve and tighten a

clear relationships to other papers in the literature, to generalize

theoretical results, to check the robustness of empirical results, to extend the analysis to

consider tela ted questions, etc.

norms

Social

Under the

aq +

(I

(a, z)-social norm.,

— a)r >

z.

papers arc regarded as worth of publication

The parameter a may

addition to reflecting what people think

while he feels that a particular high

failure to

The

it

make

should

r

still

q,

two

reflect

makes a paper

people think authors should be required to do.

in a journal,

common and commonly known.

papers are assumed to be

for evaluating

different value

valuable,

it

if

and only

judgements.

can also

reflect

is

"better" than the marginal paper

improvements required of everyone

is

While the model

illustrated below.

a.t

else.

moment

the

is

described as a four

the authors are the only ones

acting in a nonmechanical way.

1

t

=

3

Economists

Referees

Economists

Editors

choose

assess q

choose

say

q

e

[0, l]

what

For example, a referee might argue that

low r paper

step process with three groups of players,

t

In

be rejected because the good idea does not excuse the author's

timeline of the model

t=

if

report r(q)

tr

e

[o, i

-

g

yes/ no

In the first stage of the model, authors choose the fraction

t

G

q

devote to thinking up and developing the main ideas of the paper.

~

of q-quality q

t

q

F

F

Assume that

F(q\t q ).

is

Natural specifications

infinite).

mean

t

q

The

a paper

will

rn(t

[0,

result

q )]

t

is

and

q

each

>

(with m{t q )

t

q

.

or exponentially

[0, t q ]

.

model authors submit

In the second stage of the

their papers to the journal.

journal's referees correctly assess the quality q of the paper and report that

acceptable for publication

if

and only

authors are able to revise

if

aq +

quality of at least r(q) as defined by

r(q) as a

for

have the q distribution increasing in

For example, q might be assumed to be uniformly distributed on

distributed with

time to

continuously differentiablc in

has an everywhere positive density f{q\t q ) on the interval

being possibly

[0,1] of their

(1

—

a)r(q)

=

z.

it

it

The

will

be

and achieve an

r-

In practice one can think of

measure of the number of improvements rcfereees ask

for in their reports

and the

difficulty of the tasks.

amount

In the third stage authors choose the

revisions.

r

=

h(t. r )

The production

+

Assume that

h!

>

and

assume

where

rj,

is

77

of /--quality

a

random

again a

is

<

0.

To ensure

also that h'(0)

=

00,

random

tr

[0, 1

(E

is

—

t

to

q\

process. Specifically,

spend on

assume that

with a

>

0.

a decreasing returns activity with h(0)

=

0,

variable uniformly distributed on

the production of revisions

h"

of time

[0,

a]

that time will be allocated to both dimensions of quality

and

h'(l)

=

I

0.

which aq

In the fourth stage, editors accept the fraction r of papers for

+

(1

— a)r

is

highest for publication.

An

equilibrium of the model

is

a quadruple, (a,z,t*,t*(q)) such that

chosen to maximize the probability that aq

there are multiple choices that yield the

fraction of papers with

social norm,

4

if

aq +

(1

- a)r >

there exist choices of

t

q

+

(1

- a)r >

and

is

exactly

t r (q)

for

r.

I

and

t*(q) are

z (and are as small as possible

same probability

z

r*

of publication)

and such that the

will refer to (a, z) as

which

(a, z, t q

,

tr

if

(q)) is

a consistent

an equilibrium.

Analysis of the static model

In this section

I

analyze the model described in the previous section.

main observations.

First,

many

different social

norms

arc possible.

I

wish to highlight two

Second, the marginal

accepted papers tend to have relatively low ^-quality and relatively high r-quality

in the

universe of published papers.

Characterization of equilibrium

4.1

The

analysis of the equilibrium

an equilibrium

leisure, at t

3 authors will devote

r-quality unless the paper

less

time

a straightforward backward induction argument. Consider

Because of the lexicographic preference

(a, z, t* t*{q))-

=

is

all

of their remaining time to improving their paper's

sure to be rejected

is

for publications over

anyway

or

sure to be accepted even

is

if

devoted to revisions. As a result we have,

is

Proposition

In any equilibrium of the model,

1

q={z-{\- a)h{\ -

Then,

t*))/a.

q<q

let

q

=

h- l ((z-aq)/(l-a))

(For this proposition, define h~ (x)

Note that

may

q

the support of

be

less

Hence,

q.

it

is

=

if

—

(1

— a)(h(l — t*) + o~))/a and

and

(0

[

(z

x

<

if

q<q,

if

q

<

q.

0.)

may

than zero and q

be greater than the upper bound of

may

possible that either of the extreme cases

not arise for

particular parameterizations of the model.

In the first stage, the time

will

t

q

allocated to trying to develop the

main

ideas for a paper

be chosen to maximize the probability of eventual publication. Write G{z\t)

probability that

aq +

(1

— a)r

is

at

most z when

above proposition. Note that this probability

set equal to

1

—

t

q

.

G(z:t)

is

a fixed

t.

G

is

is

chosen optimally as in the

the same as

it

would be

q

maxfl,-

uniformly continuous in z and

strictly

and

rr

t,

t

if t r

was simply

Hence,

G(z;t)=J_

Note that

is

=

for the

between zero and one. Write

The equilibrium time

allocation

is

L

a

It is strictly

t.

G~

i

)f(q\t)dq

increasing in z whenever

{p;t) foi the inverse of this function for

easily described by

Proposition 2 In

any

the first stage of

the time allocated to developing q-

equilibrium.,

quality satisfies

t*

G Argm.axt G~\\ -

r\t).

Proof

In equilibrium, each economist's

satisfy G(z;t*)

=

(1

-

r).

If r*

<

accepted with probability

is

does not belong to

Argmax

£

G -1 (l

G _1 (l — r;t) > G _1 (l - r;

does maximize that expression has

increasing in z whenever

paper

G(z;

t)

which contradicts the optimality of

<

1.

t.*)

this implies that G(z,

-

=

t)

r.

Hence, z must

r;t), then

Because

z.

any

t

which

G is strictly

< G(G _1 (1 —

t; t))

=

r,

t*.

QED.

Some examples

4.2

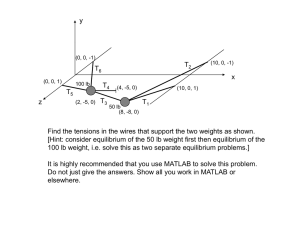

Figure

1

illustrates the distribution of

case generated by assuming that t

for r

production

has a

=

0.5

and

is

h(t r )

=

y/t T

—

=

tr

paper qualities

03, q

is

in

a "typical" equilibrium

uniformly distributed on

/2 with a

=

0.2,

and the

social

[0,

r

9 ],

—

in this

the technology

norm forjudging papers

z as 0.504.

For those parameters, the equilibrium effort allocated to q production turns out to be

t*

~

All three possible

0.S2G.

g-quality less that q

~

outcomes of a submission occur.

0.48 realize that their papers have no chance of becoming acceptable

and do not attempt to revise them. Authors of papers with

as

much time

as possible to revising (setting

tr

=

1

—

t*

accepted with probability strictly between zero and one.

q G

[<?,

papers

m(tq)

will

The

—

t*]

Authors of papers with

x

[0.68,0.83]

%

€ (q,q)

q

0.174)

(0.48,0.68) devote

and have

their papers

Authors of papers with quality

do the minimal revision necessary to ensure that their

be accepted with probability one.

figure

shows the outline of the support of the equilibrium distribution of paper

qualities in (q, r)-space.

Paper qualities are distributed with a constant density within

these regions. Papers in the lower

papers are never accepted.

left

The upper

box are those

right region

is

for

which authors set

upper region

is,

of course, r.

tr

=

0.

These

divided into a triangle of papers thai

are revised then rejected and a trapezoid of papers that are accepted.

in this

~

The mass

of papers

.

0.6

h(l-t*)+o

\

Revised

but -

mi-*:)

rejected

--

Accepted

papers

N

N

o effort

at revision

—

9

Figure

The

1:

q~U[0,t q

:

The form

=

as

much time

0.2,

a =

q

1

q

seems to

compared

=

0.3,

0.5, z as 0.504.

reflect fairly well

observation I'd like to make'

relatively low ^-quality

The marginal

=

y/i-t/2, a

of the equilibrium

One

journal

q

equilibrium distribution of paper qualities in a "typical" equilbrium: r

h(t)

\

1

1

t*

the functioning of an economics

that the "marginal'

is

to the pool of accepted papers

—

-

7

rejected papers have

they

all

have q £

[q,q\.

rejected papers are not relatively low in /--quality. Their authors have spent

as possible revising

and achieved r-qualitics that are on a.verage superior to

those of accepted papers.

While

I

think that the case illustrated above

quent arguments focus on

authors set

tT

=

t*

the primary one of interest and subse-

the equilibrium can take other forms for different parameter

Most notably, when a

values.

all

it,

is

is

— there

sufficiently small

(i.e.

g-quality

is

of

its

The

eventual acceptance a sure thing.

for

such a case: q

~

U[0,

t

is

good enough to

following proposition formalizes this obser-

paper qualities and the acceptance

vation. Figure 2 graphs the equilibrium distribution of

and rejection regions

importance)

always be some chance that any idea, no matter how

will

vacuous, can be developed into a publishable paper and no paper's idea

make

little

q ],

= v^T —

h(t r )

tr

/2,

o

=

0.2,

a =

0.2

and

finite

and

z« 0.532.

Proposition 3 Suppose

uniformly bounded for

t*{q)

=

1

—

t*

for

all

that the upper

all

q 6

t

q

E

[0, 1].

[0, rn.(t*)],

bound of the

q- distribution,

Then, there exists

i.e.

all

a >

m(t q ).

such that for

is

all

a €

(0,

a),

papers are reuised to the greatest extent possible

10

h{l-t*)

+o

Accepted

papers

0.6 -•

h(i-t;)

Revised

but

rejected

t*

q

Figure

T

=

2:

0.3, q

An example

~

q

\

a" equilibrium:

of the equilibrium quality distribution in a "low

U[0, t q ), h(t)

and no paper achieves

q

=y/i-

t/2,

a =

a =

0.2,

0.2, z tv 0.532.

a level of q- quality sufficient to ensure that

it

will be accepted with

probability one.

Proof

To

see that q

<

note that

if

a paper with q

and gets the best possible draw on r-quality

=

is

revised to the greatest extent possible

its overall

quality will be (1

— a)h(l —

t*)

+ a.

In equlibrium,

Probjary

+

(1

- a)r >

(1

-

a){h(l -tl)

7

+ a)} <

Prob{r >

a

<

1

For

a

sufficiently small the expression is less

of the paper with q

=

than

r,

Ml -

—>

•m{t*)f<j

q'

-a

+a

1

as

q —

»

-m(t*)}

H

—a

0.

'"

and hence there

is

a positive probability

>

m(t*) note that

if

a paper with g-quality m(t*)

the greatest extent possible but gets the worst possible draw on r-quaHty

+

(1

- a)h(l -

Pvob{a<7+

(1

- a)r > am(i!) +

am{t*)

¥

being acceptable.

Similarly, to see that q

level is

tl)

t*)

revised to

is

its overall

quality

and

(1

- a)Wl -

t*)}

>

Prob{r > h(l -

t*)

H

+

1

>

<xm(t* )

1

q

cr(l-a)

11

1

as

a

—a

-»

0.

H

Hence,

the best r

<

any r

for

is

the probability that a paper with g-quality m(t*)

1

strictly positive

a

if

is

fails

to be

among

sufficiently small.

QED.

Some

of the results

I'll

give later will

the statements of these results

I

depend on the form

will give the

To

of the equilibrium.

simplify

forms pictured in the figures (and a couple of

other forms) names.

Definition

q

It

1

< m(t*} and

r(m.(t.*))

>

has the "som.ewhat low

0<q<q<

an equilibrium

/ will say that

0.

An

a"

form, if

m(t*) and r(m(t*))

The somewhat low a form

is

"typical" or has the typical

is

a"

equilibrium, has the "low

<

<

<

q

m,(t*)

<

q.

form,

It

is

if

<

q

if

<

<

m(t*)

q

<

<

q.

a" form

"high

of the

if

0.

similar to the low

a

form, with the only difference being

The

that in the former authors of the lowest q papers do not revise their papers.

is

form

similar to the typical form, but the highest q papers are so

good that

r(q)

high,

a form

negative,

is

i.e.

they revised the paper to

make

it

be publishablc. The authors of these papers obviously exert no

effort

on revisions and have

referees

tell

die authors that even

if

their papers accepted with quality to .spare. In the

a

—

0.2

and r

=

0.3 the equilibrium has the low

low a form for

a G

high a form for

a £

a form

for

(0.2286,0.3363), the typical form for

(0.5870,

1).

q

if

the distribution of q

is

~

a €

U[0,

t

q \,

would

it

h(f)

=

still

\/i—

r/2,

somewhat

(0,0.2285), the

a €

In other specifications for the

take on other forms. For example,

will

model with

worse

(0.3364,0.5869) and the

model the equilibrium can

unbounded

(or r

is

large)

we

simultaneously see papers of the lowest g-quality being resubmitted and papers of the

highest g-quality being accepted with no revisions.

4.3

In the

The

multiplicity of consistent social

model described above not

all

norms arc

social

in the journal for a small fraction of papers,

Thi.v however,

community

is

really the only constraint.

norms

consistent.

If

there

is

only room

then the quality threshold z must be high.

.Nothing in the model restricts the weight the

places on 7-quality versus r-quality. There are a continuum of consistent social

norms with any a being

possible.

The

following proposition gives a formal statement to this

12

effect,

h{t)

=

and Figure

s/i.

-

t/2,

3 graphs the set of consistent social

a

=

Proposition 4 In

0.2

=

and r

is

for the

model with

~

q

U[0,

t

q ],

0.3.

the m.odel described above, for

such that (a,z*(a))

norms

any a 6

[0, 1]

there exists

an unique z* (a)

a consistent social norm,.

Proof

For any fixed a,

Because

for all

G

is

z*(a) to H(z)

It is

G{z;t) be the

uniformly continuous,

is

II

t,

let

continuous with H(0)

=

1

—

t.

(a, 2*(q))

is

CDF of aq+(l-a)r

t is

an agent setting

t.

q

H(z)

=

inf t G(z;t).

chosen from a compact set and lim 2 _4oo G(z;

=

and lim z _oo^(z)

=

1.

Hence there

t)

—

1

a solution

is

a consistent social norm.

not possible for both (a, z) and (a,

In that case,

as above. Let

z')

to be consistent social

norms with

z

equal to the the equilibrium choice under the (a,z')

would surpass the z threshhold with piobability greater than

<

z'.

norm

r.

QED.

z

i

0.5 --

I

Figure

r

=

3:

0.3.

Consistent social norms (a, z) in the model with q

and a

=

Explanations

My

view of the trends

for

in

observed increases

=

y/t

-

t/2,

clear that a

in /-quality

economics papers mentioned

be thought of as aspects of an increase

makes

U[0,t q ], h(t)

0.2.

4.4

all

~

a

number

in

in the

introduction

is

that they can

the r-quality of published papers.

The model

of different explanations for such a change are possible.

13

The explanation

published papers

I

focus on in the latter half of this paper

will increase

if

a

decreases,

i.e.

if

norms

social

that the r-quality of

is

shift to place; relatively less

emphasis on q-quality and relatively more emphasis on r-quality. This raises the r-quality

of published papers for

two reasons: economists react by allocating more of

their time to

producing r-quality; and when choosing from the pool of resubmitted papers the journal

places

more emphasis on

r-quality.

Other plausible explanations do not require a change

and

One

r.

is

in social

that the technologies for producing q and r

norms

may have

shifted over time. For

example, one could argue that economists have begun to exhaust the set of

and model

change

this as a

in F{q\t q ) that

one could argue that advances

in

latter explanation

reducing r has two

A

q

Similarly,

.

second potential explanation

may have become more

is

competitive.

not straightforward, so

First,

effects.

it

I'll

discuss

more

allows the journal to be

from the pool of resubmitted papers. Second,

of

f

We

is

that

might think of the

in r.

and

this

might

standards in both dimensions. 6

raise quality

If

possible ideas

computer technology or accumulated knowledge allow

growth of the profession and other factors as equivalent to a decrease

The

all

reduces the marginal benefit of

authors to produce more r-quality per unit time.

publishing in the top journals

for trading off q

it

affects authors'

it

Intuitively,

further.

selective

when choosing

time allocation decisions.

authors react to increased competition by gambling on bold projects that require a

t.

q

.

the second effect could offset the

first

and make the

overall effect of competition

lot

on

r-quality ambiguous.

Formally,

C _1 (l — r;

is

t

q

)

should note

I

first

that nothing in the assumptions so far guarantees that

(which plays the role of the economists' objective function when

quasi concave.

If,

for

example, q

~

[/[0, kt?}\

with n

>

1,

a discussion as

by

just

I

t* will

change discontinuously

in the

Ellison (2000) notes that

moderate, but that decreases

is

such that

t*

is

the

relative status ol the top journals

number

may have

I

To provide

will avoid

in the profession

also contributed to

will

as simple

such complications

t)

=

over the last 30 years has been

some top journals and an increase in the

a more substantial increase in competition.

of articles published by

14

selected)

the unique solution to ^(z*(a.r);

by many measures the growth

in

is

and some higher value of t q

parameters.

can of the potential effects of r on r-quality,

assuming that F(q:t)

q

then the production of g-quality

would involve increasing returns. In some cases, both both

be local optima and

t

among, values of

standard

is

which G{z*{a,r)\f) <

for

t

strictly

concave at the optimum,

and that the probably of achieving the

1

T (z"(a,T):t*) >

i.e.

0.

^gj

Recall that t*{r) solves

dG

~(z*(r);t*q (r))=0.

dt

Differentiating with respect to r gives

z*

is

always decreasing

in

r and we have assumed that ^p~

§^§i{z"'{r);t*(T))

<

To think about the

decreasing in r

if

that |J(z;

the density of the overall quality distribution.

t

q

is

)

0.

more spread out when authors spend more time thinking

of r-quality

is

which case the Jj^f

negative. In this case,

is

the overall effect of r on r quality

For

a.

more

is

q.

is

is

marginal

rr

new

t* will

ideas

more

functional form like F{q\t q )

sensitive to

t

q

tT

only shift the

for a

mean

be decreasing

increase as r decreases, and

authors setting a times the effect of

When

the journal

is

is

~

more

t

q

cm

their luck being

highly nonselective,

When

the journal

on getting nearly as a good a draw as possible on

(7[0,

t

q ],

the higher percentiles of the q distribution

investcments. Hence the return to

on the paper being marginal

be

and the production

conditioning on getting a very bad draw from the q distribution.

With a

will

the q distribution becomes

on r-quality conditional on

the journal.

for

extremely selective, the conditioning

are

t* reflects

- a) times the effect of

(1

such that their paper

this

If

for the density to

is

t*

may be ambiguous.

direct intuition note that

q-quality equal to

outcome

Hence,

sign of this derviative note

a more deterministic: process in which increases in

r-quality [as we've assumed), then the natural

in tg, in

of

positive.

is

t

q

is

greater

when one conditions

selective journal.

Figure 4 illustrates the effects of changes in r on time allocation and quality in a model

with q

~

(7[0,fJ, h{t)

= Vt -

monotonically decreasing,

right panel

shows the

i.e.

t/2,

/*

effect of r

a

=

0.2,

and a

=

0.5

increases as the journal

on the mean

q-

The

left

panel shows that

t* is

becomes more competitive.' The

and r-quality of the published papers. The

The shape of the figure when r is near zero is sensitive to the distributional assumptions. \Vi<h the

uniform specification the maximum possible return to /, is bounded and t" is bounded away from one as T

q

approaches zero. If q had been specified as exponentially distributed with parameter t q the effect of r, on

,

—

t1

percentile of the q distribution would grow without bound as r approaches zero

spent on revisions would decrease all the way to zero in the limit.

the

1

15

and the time

beween r and r-qnality

relationship

is

nonmonotonic. At some points the

effect of r

on

t*

dominates, while at others the effect of journal selectivity dominates.

$

T

1

Time

Figure

5

A

The

static:

4:

Effect of journal selectivity

model above has a continuum of equilibria corresponding to

I

describe a dynamic model of the evolution of norms.

common

common

The model

belief.

who

The model

are trying to learn and apply the profession's

Instead, the

beliefs at every point in

to learn the prevailing

all

different social

when one hears the term

"learning model"

not model agents as arriving with different beliefs and examine whether there

convergence to a

t,

r

quality of published papers

on time allocation and observed paper quality

standards. In contrast to what one might think

have

r

dynamic model of evolving norms

involves a population of author-referees

will

q

Mean

1

Mean

allocation

norms. In this section

I

Mean

norm

model

time and

involves a discrete set of time periods

it

as in the static

receive via referee reports

This focus

is

and

game

is

of Section 2

nol intended to suggest that whether a

on

and Fudenbeig (2000), the common

will

on whether agents' attempts

8

t

=

0, 1, 2,.

(at,zt).

.

.

and serve as a

community

.

At the

They then

editorial decisions will suggest to

effects of belief or preference heterogeneity

in Ellison

be constructed so that agents

will focus

I

lead to a shift in norms.

economists believe that that the social norm

try to publish

will

is

start of period

write a paper and

referee.

The data they

them that the

will reach a

social

norm

common norm and

the

he evolution of social norms are not interesting. Instead, as

beliefs learning model is motivated solely by the desire for a

I

tractable model that highlights an important effect.

16

is

in fact, (at, z t ).

This leads them to alter their beliefs aceording to

-a

a t+ i

-

zt+i

for

some constant

gather and

What

First,

A:

>

To complete

0.

t

,

zt

the specification

must describe what data economists

I

inferences (d ( z t ) from the data.

how they draw the

,

data do economists get?

assume that economists get two types of data points.

I

when an author submits a paper

of quality at least q

I

assume that the

he or she receives give him or her a data point of the form

should

on the

all lie

line

a

t

q

+

{1

- a

t

)r(q)

=

zt

.

I

will allow,

In particular,

I'll

r(q))

9

These datapoints

however, for the possibility

when judging the

that economists arc subject to an overconfidence bias

own work.

(q,

referee reports

quality of their

assume that they overestimate the r-quality of

their initial

submission and this leads them to believe that they have been required to achieve an

quality that

r-

10

In this

higher than what they have actually been required to achieve.

is e

—a

=

+

—a

q

+

(1

Second, whenever an economist referees a paper that

is

of sufficiently high quality to

case, the (q,r(q)) datapoints actually

lie

on the

line

a

t

t

)r(q)

zt

(1

t

)e.

be

1112

Economists

resubmitted he or she gets a data point of the form (g,r, Accept/Reject).

expect to sec

all

papers lying above the line atq

papers lying below this

If

line

finite

number

To keep the model tractable

Note that

as to

make

it

in a slight

list

it

Q/)r

=

zt

being accepted and

all

I

if

they entered the model with

common

avoid this by invoking word-of-mouth communication.

departure from the static model I've assumed that journals do not provide the

make the paper publishable if the paper's q-quality is so low

of revisions sufficient to

inconceivable that a revision will be publishable.

of journal practices.

because

—

of data points, then their analyses would lead

to a divergence in the second period beliefs even

author with a

(1

being rejected.

economists each saw a

beliefs.

+

I

I

believe that this

is

a good description

did not try to incorporate such behavior by referees in the static model, however,

seemed a needless complication and because it creates a possibility for another type of equilibrium

I did not feel was important: authors won't save time for revisions if referees won't ask for

multiplicity that

large revisions because they don't think they're feasible.

Given that the acceptance fronteir is downward sloping in q-r space this assumption is almost equivalent

assuming that authors believe their papers to be of slightly higher q-quality than they actually are, or

to assuming that have biased views of both the q- and r-quality of their work. I've chosen the formulation

above because it makes some results a little cleaner (especially those about small a behavior.)

Another important data source for real world economists is reading journals. Given the word-of-mouth

assumption below, this would just provide redundant observations on all of the acceptances. For this reason,

nothing would be changed if 1 included this data source in the model.

An ambiguity in the model is what happens if the assumed standards is so excessively high that fewer

than r papers are resubmitted. In the simulations in the next section I assume that in this case editors

accept some papers that aie not resubmitted and that these acceptances are observed by the referees.

to

17

I

talks to every other economist in each period

assume that each economist

sees

all

author's

of the data points that were generated in that period.

While

experiences a measure zero subset of his or her datasct,

own

I

this

and thereby

makes each

do not want to

lose

the possibility of inferences being affected by the authors' misperceptions of the quality of

their

own work.

I

thus assume that the {q,r(q)) observations economists receive by hearing

others taik about the referee reports they received are contaminated by the author's bias

(and that the listeners do not realize

What do

this).

economists do with the data they obtain each period? Fitting the (a,

involves estimating the slope and intercept of a line that

fits

z)

model

the {q,r(q)) data and divides

the acceptance and rejection regions. Typically, no line will do both jobs perfectly.

I

assume

that this does not cause economists to lose faith in their model of the world and that they

go ahead and try to

Formally,

I

fit

13

the data as well as possible with the («, z) model.

assume that economists' period

(d

where L(a,z)

is

describing the

(q,

fit

I

,

a loss function

r(q)) points

the hypothesis that

Specifically,

t

all

zt

)

analyses take the form

= argminLfa, zj/zi,^),

a, z

tha.t

describes

and a measure

referees

t

\i 2

how

poorly the the data (a measure

describing the

(q, r.

/.i\

Accept /Reject) points)

and the journal editor are applying the

(a, z) social

norm.

assume that

L(a,

z;

m, fi 2 = Li(a,z;m) + L 2 (a,z;fi 2 ),

)

where

Li(a,

is

z;

fj,i)

=

/

(r{q)-

—

2

^

d/zi(g),

I

a

J

a standard mean squared deviation measure of the distance

the {q,r(q)) data points and the line 0*7

L z {a,z:n2 )=

iRu A

(

V

—- a

1

+

(1

- a)r =

r)d/.i 2 {q,r)+

)

z

(in

the r-dimension) between

and

('"--7

Jr vr

\

I

-a

M/*2(g,r).

J

Formally, economists are estimating a misspecified model.

A justification for not worrying about

economists noticing the misspecification is that in a more realistic model economists would only receive

a finite number of datapoints and there would be a random component to each observation, so the form

of the misspecification would not be so appaient. The idea that economists struggle to reconcile haid-toreconcile observations while maintaining biased self images does not

18'

seem

unrealistic to

me.

where

Rua

failing to

is

the set of

meet the

which papers were "unexpectedly accepted" despite

r) values for

(17,

standard and

(ct,z)

Rur

i

s

'he set of '"unexpectedly rejected" papers

that met the (a, z) standard but were rejected. L2 can be thought of as the product of the

fraction of accept/reject decisions that are inconsistent with the (a, 2)

(in the

age degree of error

model and the aver-

r-dimension) that appears to be embodied in the "unexpected"

decisions.

Obviously other

loss functions

would be reasonable. The most natural would probably

be the negative of the log likelihood of the data under a hypothesis involving referees and

the editor trying to apply the (a, 2)

norm but making

idiosyncratic errors in judging the

quality of each paper. Analyzing such a specification would require cxaminining integrals of

CDF's and PDF's, however, and

in

I

felt

that the specification above was the best compromise

terms of reflecting a similar goodness-of-fit notion and being tractable.

6

Analysis of the dynamic model with no overconfidence bias

(e

=

0)

In this section

dynamic model when economists do not have

discuss the behavior of the

I

an inflated view of the quality of their own work. The main observations arc that consistent social

norms arc steady

states of the

model and that when

referees are too

demanding

economists infer both that their standards were too high and that g-quality must be

tively less

important than they had thought.

6.1

Steady states

When

there

is

no overconfidence bias

the static model

is

Then, (a

t

,

it is

easy to see that any consistent social

norm

of

a steady state of the dynamic learning model.

Proposition 5 Suppose

norm..

rela-

zt

)

=

e

=

in the

(ocq, zq)

for

all

dynamic model and

(oq, zq)

is

a consistent social

t.

Proof

All points (q, r(q)) in the

c*o<7+ (1 -cto)r(q)

=

z

.

The

data obtained from

referees' reports lie exactly

editor's decisions are also consistent with

19

on the

imposing the

line

(0.0, 20)

standard,

+

a$q

i.e.

all

— ao)r —

(1

the ^-distribution

zq

is

always nonnegative)

=

(ao,zo)

— Q'o) r

rejected papers have ao<7+ (1

>

~ zo

<

and

Hence, both L\ and L2 are zero for (a,

0.

nonatoinic on a continuous support, L\

for

all

any other

(a, z).

is

accepted papers have

z)

=

(c*o, zo)-

Because

strictly positive (and

The unique minimum

of the loss function

is

L2

is

thus

(ao, zo)-

QED.

Disequilibrium dynamics

6.2

In this section

I

discuss the disequlibrium behavior of the

in this section (and in the

for (/-production, q

~

remainder of the paper)

The whole

U[0,t q }.

what

of

want

norm

The

figure

was constructed by solving the model numerically

the figure

is

~

U[0,1 q ], r

=

0.3,

14

figure at

To

a =

a

—

and

0,2

help organize the dynamics

0.3363. This

is

I

—

o?, z/ + ]

—

zj)

for various initial beliefs

h(t)

the locus of consistent social norms (a, z*(a)).

are proportional to the change in beliefs (a/ + i

beliefs.

of economists' beliefs about

(a, z) outside of equilibrium follows the pattern illustrated in Figure 5.

under the assumption that q

line in

results

to say in this section can be

summarized concisely by saying that the dynamic evolution

the social

The

concern the uniform technology

will

I

dynamic model.

=

The

yjl

—

t/2.

vectors in the figure

that occurs for various initial

have also placed a vertical dashed

where the equilibrium

shifts

The sohd

line in the

from the somewhat low a form

to the typical form.

The

regions.

locus of consistent social

norms and the dashed

line divide (a,z)

In three of the four regions the learing process

is

space into four

mostly just a straightforward

adjustment of the overall quality threshold: when referees try to impose a standard that

would not allow the editor to

that they must reduce

2;

when

fill

the journal they infer from the unexpected acceptances

referees are too soft

and the editor has to turn down some

papers they recommend they learn to choose a higher

14

The speed

z.

15

is determined by an arbitrary scaling parameter k.

Note that unlike all other graphs in this paper the x and y axes in this figure do

not have thf same scale. The j/-axis has been magnified by a factor of 1.5. These choices reflect an attempt

to maximize ihe visibility of the directions and minimize clutter.

I5

The dynamics in the 2 < z*(q) and a large region fit this desciiption only if a is not too large. I discuss

what happens in the "high o" case at the end of this section.

The

with which beliefs change in the model

figure uses k

=

0.6.

20

0.2

0.1

Figure

What

is

0.3

The

5:

high.

i.e.

''typical'''

z

most important

>

z'(a).

0.7

to

my main argument

5.

is

what happens

Suppose that the (a

t

,Zt)

0.9

0.8

norms when

disequilibrium evolution of social

the upper right part of Figure

-

0.6

0.4

f

=

a

1

0.

in the fourth region

standard

is

unreasonably

Suppose also that the distribution of resubmitted papers has the

form. Economists will then (correctly) perceive that referees are asking

them

to

meet a very high standard and that some papers that they thought were submarginal are

being accepted. The conflict in this data leads economists to do two things: to believe that

quality standards are less

is

relatively

To

demanding than they had thought; and to

believe that r-quality

more important than than they had thought.

illustrate

why economists make

this inference, Figure 6 contains

of the data economists get in one such case. 16

The

apoints they get from referee reports.

quality distribution. All papers above

The bold

outlined area

and to the

an enlarged view

line represents the (q,r(q)) datis

the support of the (uniform)

right of the bold line are accepted.

The

journal editor also accepts papers in the shaded region (to the surprise of the referees).

Lower quality papers are

The

Hid

z

=

rejected.

The

figure graphs the quality distribution

0.53417 with q

~

U[0A. q

}

t

h(l)

=

y/i

-

lines

below the g-axis and to the

and the best fit (d, £) when

t/2, a = 0.2 and r = 0.3.

21

left

of the r-axis

initial beliefs are

that a

=

0.5

support of the q and r distributions

illustrate the

among resubmitted

papers.

have used

I

bold lines to show the support of the quality distribution for the unexpectedly accepted

papers. These papers are at the low end of the q distribution and at the high end of the r

distribution. Economists' rationalize these acceptances in part

be more important than they had thought. The dashed

that best

gives a

fits

good

The

the data.

fit

flatter line

accounts for

line

by concluding that

r

must

graphs the social norm (a,

many unexpected

z)

acceptances and

to the high q part of the [q,r(q)) data.

(q,r(q)) data

-t*)

/?(1

+a

Expected

acceptances

/?.(]

-t

Best

5

Figure

6:

2

-1

«

1

9

q

fit

Economists' inferences when standards are too high: the "typical" case

Figure 7 contains a similar diagram illustrating economists inferences

beliefs

(a t ,z

t

)

a

are unreasonably tough and

t

resubmitted papers has the "low a" form -devote the same

maximum

is

sufficcntly

all

fit is

when

papers are resubmitted and

effort to their revisions.

referees'

low so that the distribution of

all

authors

Here, the "unexpectedly accepted"

papers are uniformly distributed in the q dimension, and the dotted

best

to data

line illustrates that the

obtained by slightly lowering z while leaving the slope of the line unchanged.

Even with the simple

loss function I've chosen, getting analytic expressions for the

optimal inference given an inconsistent (q

(

zt

,

)

is difficult.

Proposition 6

is

a characteri-

zation of the dynamics that brings out the main observations I've mentioned above.

proposition characterizes the dynamics for

i.e.

for zt close to

z*(a

t

).

Parts

(a)

and

initial beliefs

that are close to being consistent,

(b) note that in the low

22

The

a and somewhat low

J

L

r

{q,r{q)) data

U.

/

—

/

«.

"

0.6

-

U.o

-

Expcc:ted

/ acceptances

^^-^-^-Ct^r^: --^1^.

:

Suprise acceptances

,J1^

Best

fit

to data

.

Expected rejections

1

t*

g

Figure

a

7:

when standards

Inferences

a standard that

toward z*(a

is

t

Part

).

(c)

my main

a

notes that

(at least

when

approximately) and adjust

referees' beliefs

correspond to

too low the dynamics are similar in the "typical" case: the dynamics are

approximately vertical when the social norm

to

are too high: the- "low a" case.

cases economists do not adjust their estimate of

their estimate of z

Q

0.5

observation.

notes that

It

involve both a reduction in

a and

counting for the change that

is

when

is

approximately consistent. Part (d) relates

zt is

slightly larger

than z*(at) the dynamics

a reduction in the overall quality standard (after ac-

induced mechanically by the change

two parameters arc comparable

in

The

in a).

magnitude. The proof of the proposition

is

shifts in the

contained in

Appendix A.

Proposition 6 Consider

the

dynamic model described above with F(q\t q )

~

(7[0, t q }.

tq(a.z) be economists' optim.al time allocation when, they believe that the social

(a,z).

(a)

Write b(z)

sa

a{z

—

z*(a)) as shorthand for lim,^,.( Q )

Suppose that for a given Q( £

has the low a form,.

(0, 1) the

i

zt+\

-

t

=

zt

=

Then, there exists a constant a

o.(z*(a

t

)

-

2

(

x

=

)

23

>

such that for

zt

norm

is

a.

unique equilibrium for the social

of z*(q() the dynamics have

a t+ - a

T _,'f (

Let,

norm

(at, z*(cxt))

in a neighborhood

(b)

Suppose that for a given at £

has the somewhat low

a form and

there exists a constant a

Q't

zt+i

For

(c)

a*

~

~zt

~

-

+i

(0, 1) the

>

-

o.(z*(a t )

<

has the "typical" form, and z t

t

t

«

zt

Rs

-a

+i

zt+\

-

to

z*{a

at.

the

t )

t

=

t

(a ,z*(a

t

q

t

)).

Then

dynamics have

—

= 0.

unique equilibrium, for the social

Then

z*(at).

aj

norm

>

there exists a constant a

(at, z*(at))

such that for

zt

dynamics have

-

a.(z*(a,)

has the ''typical" form, and z

z,),

t

(0, 1)

>

the unique equilibrium, for the social norm, (at, z*(at))

z*(a t ).

Let

>

Then, there exist constants a\

l-oc.

strictly positive

dynamics have at+\

(0, 1) the

Suppose that for a given at 6

(d)

is

zt )

Suppose that for a given at G

close to z*(a{) the

—^-

such that for z t close

larger than. z*(at) the

zt slightly

a

that

unique equilibrium for the social norm, (at,z*(ctt))

M

=

q

and «2 >

(q(at,z t

)

+

t

q

(at.z t ))/2 and

such that for z

t

M

T

=

close to z*(at) the

dynamics have

q, + 1

z t+ i

t

«

-ai(z - z* (a

zt

«

a 2 (z* (a

-a

-

The one notable

is

is

a form

for

-

zt

)

))

+

(a t+ i

- a )(Mq t

z

<

z*(a) and

a

is

I

M

have

apparent from the figure that

why economists conclude

when standard

r

)

left

out of the discussion so far

sufficiently high so that the equilibrium

in this case

more important than they had thought.

relatively

argument

It is

t )

t

feature of the Figure 5 that

what happens when

the high

q

t

that r

is

economists conclude that

The argument

is

similar to the

more important than they had thought

are too high in a typical equilibrium.

The unexpectedly

rejected papers

arc relatively low q papers and hence a steeper line allows referees to account for

the unexpected rejections while maintaining a good

I

fit

have not discussed this case in more detail because

here seems less plausible.

First,

it

has

many

of

to the r(q) data for high q papers.

in

a couple of ways the argument

involves economists mistakenly not achieving levels of

24

r-quality that they could have achieved. Second, the effect derives from economists trying

to

datapoints with

fit

negative.

The overconfidence

7

In this section

I

and gradual evolution

bias

show that adding a

to place ever

in

which

more emphasis

r-quality.

e-perturbations of dynamics with a continuum of steady-states

7.1

Before discussing the model,

dynamic model

is

of the

it is

instructive to discuss

~t+i

(pi,z)

= argmm QjZ

L(a,

~

zt

z.\a. t ,zt).

_

\

\

where

more

stucturc in

its

generality.

The

form

a t+ - a t

is

produces a model

slight overconfidence bias

norms can slowly and steadily evolve over a long period

social

on

r(ij)

,

a ~

/

J

\

A

social

t

zi.

at

zt

norm

(at,z

t

is

)

a steady-state only

if it

a solution to

—-{a u zf,a u zt) =

aa

dL

<

-T-K^L-,zuat,zt)^

OZ

This

is

—

n

a system of two equations in two unknowns. Ordinarily, one would expect such a

system to have one solution (or zero or a few). The fact that the dynamic model of the

previous section has a continuum of equilibria indicates that

What happens

it

slightly?

if

it is

we take a dynamic model with a continuum

The answer

depends on how the system

of course

is

somewhat

special.

of equilibria

pertubed.

and perturb

To take a simple

example, consider a dynamic of the form above with the loss function