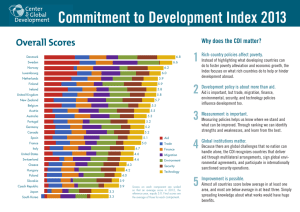

The Commitment to Development Index: 2005 Edition David Roodman

advertisement