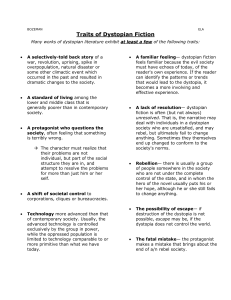

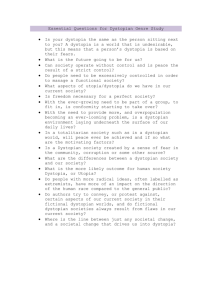

Dystopia and Apocalypse The Emergence of Critical Consciousness

advertisement