Teaching at an Internet Distance: the Pedagogy of Online Teaching... The Report of a 1998-1999

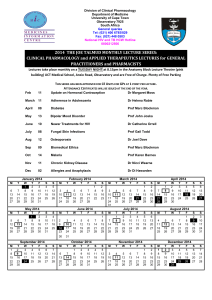

advertisement