jEMEjn lll|II|ili|ll|l«l MIT LIBRARIES

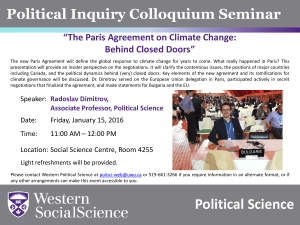

advertisement