Telling the Future Together

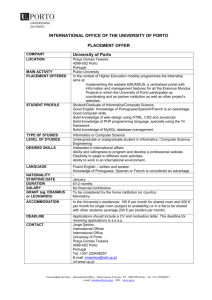

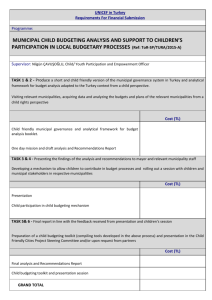

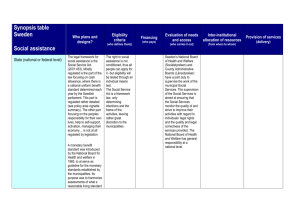

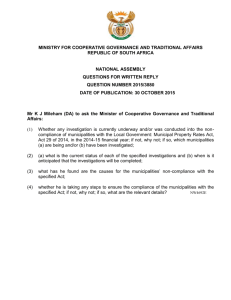

advertisement