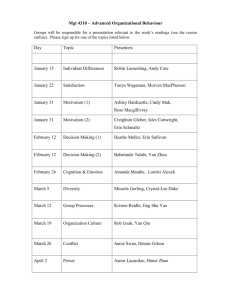

Technological Initiatives for Social Empowerment:

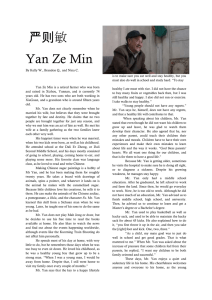

advertisement