V0O

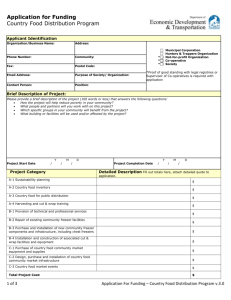

advertisement