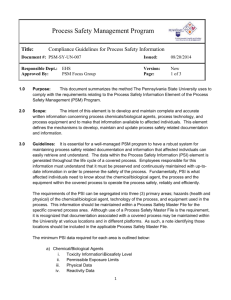

Independent eva luat ion

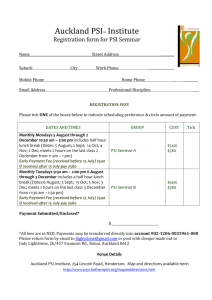

advertisement