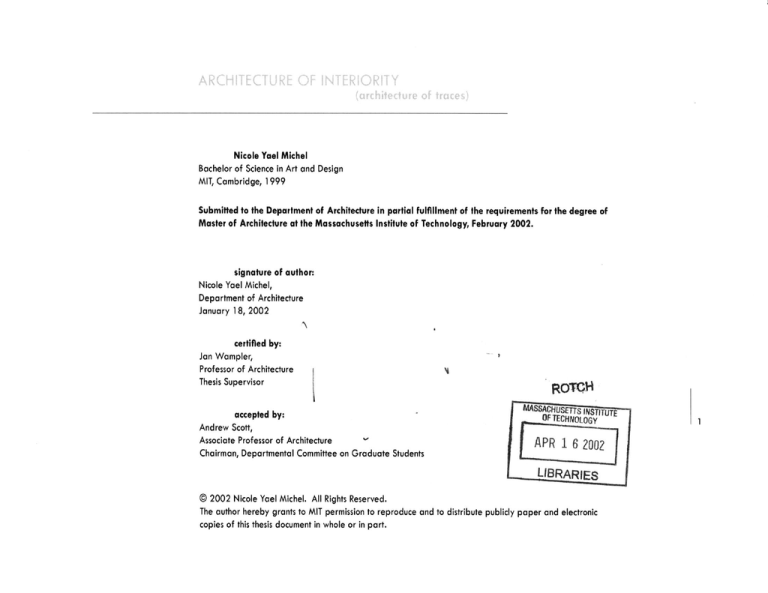

Nicole Yael Michel 1999

advertisement