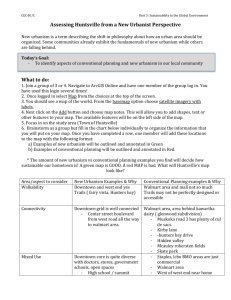

A Variation of the New Urbanism:

advertisement