Conflict Management Strategies for Real Estate ... Toward A Systems Approach for Decision Making

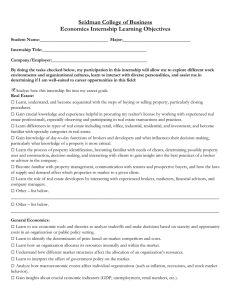

advertisement