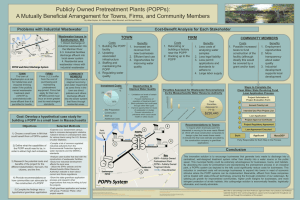

Publicly Owned Pretreatment Plants: and A Mutually Beneficial Arrangement for Towns, Firms,

advertisement

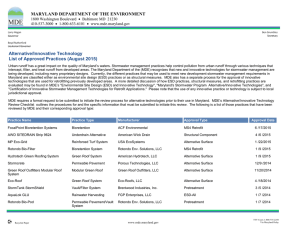

Publicly Owned Pretreatment Plants: A Mutually Beneficial Arrangement for Towns, Firms, and Community Members Under the Clean Water Act (CWA) National Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES), any entity that discharges effluent into waterways (via point source) must apply for a NPDES permit. The EPA’s enforcement of the CWA protects our nation’s water quality and prevents habitat destruction; however, NPDES permits are costly for businesses. One way that businesses can bypass the NPDES permitting process is to discharge into publicly-owned treatment works (POTWs) that are certified to treat the chemicals in effluent and discharge through the single POTW NPDES permit. However, businesses must pre-treat their effluent in order to reduce the pollution to a level that can be effectively controlled and discharged by the POTW. In the current system (using Easthampton, MA as a case study and as depicted in graphic 1), the pretreatment requirement is often costly for businesses and, subsequently, can discourage industrial expansion to new locations. Graphic 1 One innovative solution is to encourage businesses that generate toxic waste to discharge into a centralized, well-designed treatment system, which incorporates a publicly-owned pretreatment plant (POPP). This municipal facility could be extremely advantageous for businesses, towns, and habitats. By absorbing the costs for pretreatment and standardizing the pretreatment process in an industrial park, a POPPs system (as depicted in graphic 2) could significantly reduce the price of production for businesses and could provide the sense of stability desired by all production entities. This reduction in overhead costs will encourage businesses to expand into towns in need of economic stimulus where the POPP system can be implemented. Meanwhile, effluent from these companies will be treated with state-of-the-art technology, ensuring the thorough protection of our nation’s treasured waterways. Graphic 2 By yielding job growth for impoverished communities, higher profit margins for businesses, and more stringent protection of at-risk habitats, this cutting-edge solution is economically feasible, logistically attainable, and morally admirable. Moving Forward: Where to Go From Here With the above information as a starting point, this project has much room for growth and expansion. In order to quantify the feasibility of this system, it is necessary to determine the fiscal costs associated with the construction and maintenance of a POPPs facility. Next, this must be compared to the cost incurred by current companies while constructing and maintaining individual pretreatment equipment. This information should be condensed into the form of a grant proposal and subsequently presented to an organization, such as Clean Harbors (www.cleanharbors.com), in order to receive funding. With the Easthampton facility as an experimental case study, the POPPs system could easily prove to be viable at a national scale. Contacts • Zygmunt Plater: Professor of Law at Boston College Law School, teaching and researching in the areas of environmental, property, land use, and administrative agency law. o o plater@bc.edu (617) 552-4387 • Harlan Doliner: Adjunct Professor of Law at Boston College Law School. His diverse practice focuses on strategic environmental risk-assessment, management and regulatory compliance and enforcement defense; maritime security/environment/technology issues; complex facility siting; waterfront redevelopment; real estate and corporate transaction risk evaluation and support; hazardous waste site reuse and the full spectrum of land use issues and permitting. o hdoliner@verrilldana.com o (617) 309-2617 • Gabrielle David: Visiting Assistant Professor at Boston College with expertise in fluvial geomorphology, hydrology, river restoration, and environmental geology. o gabrielle.david@bc.edu • Michael Martina: Boston College class of 2015. Publicly Owned Pretreatment Plant Project coordinator during the spring semester of 2015. o michaeleliomartina@gmail.com o (303) 917-2956