Document 11130998

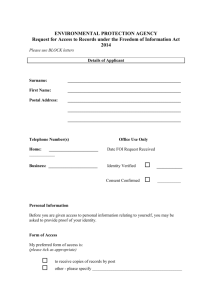

advertisement