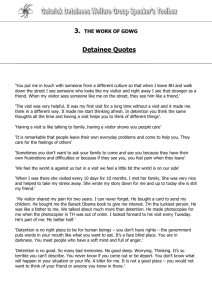

The use of detention and alternatives to policies

advertisement