Document 11120026

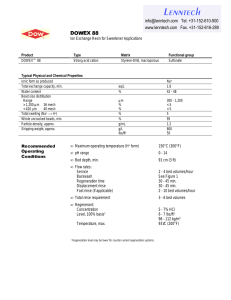

advertisement