Guide to collaboration between the archive and higher education sectors

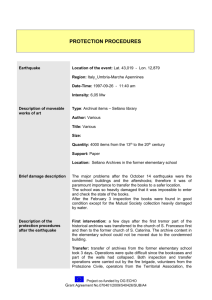

advertisement