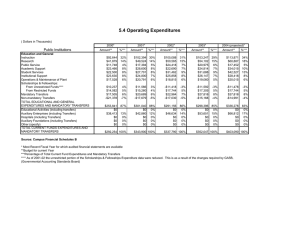

Cash Tra nsfers Evidence Paper Policy Division 2011

advertisement