Probabalistic quantification of intermittently A.

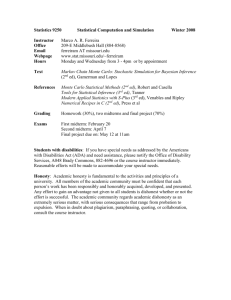

advertisement

Probabalistic quantification of intermittently

ARCHIVES

unstable dynamical systems

MAAHSETTSL INSTITUTE

OF TECHNOLOGY

by

OCT 01 2015

Mustafa A. Mohamad

LIBRARIES

B.S., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (2012)

Submitted to the Department of Mechanical Engineering

in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Master of Science in Mechanical Engineering

at the

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

September 2015

@

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2015. All rights reserved.

A

Author ..............

Signature redacted

Department of Mechanical Engineering

August 7215

Certified by............ ....

Signature redacted

is P. Sapsis

Th

anical Engineering

Assistant Professor of lc

Thesis Supervisor

Signature redacted

.

Accepted by

David E. Hardt

Professor of Mechanical Engineering

Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Theses

MITLibraries

77 Massachusetts Avenue

Cambridge, MA 02139

http://Iibraries.mit.edu/ask

DISCLAIMER NOTICE

Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable

flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to

provide you with the best copy available.

Thank you.

The images contained in this document are of the

best quality available.

ii

.Wgml

N!~'IU

$!i

'vllpmiwlFE

9iM1N'sR

1

Ikyp

Probabalistic quantification of intermittently unstable

dynamical systems

by

Mustafa A. Mohamad

Submitted to the Department of Mechanical Engineering

on August 7, 2015, in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree of

Master of Science in Mechanical Engineering

Abstract

In this work we consider dynamical systems that are subjected to intermittent instabilities. The presence of intermittent instabilities can be identified by large amplitude

spikes in the time series of the system or heavy-tails in the probability density function

(pdf) of the response. We formulate a method that can analytically approximate the

response pdf (both the main probability mass and heavy-tail structure) for systems

where intermittency is important to quantify. The method relies on conditioning the

probability density function on the occurrence of an instability and the separate analysis of the two states of the system, the unstable state and the otherwise stable state

with no intermittent events, according to a total probability law argument.

In the stable regime we employ steady state assumptions, which lead to the derivation of the conditional response pdf using standard methods for random dynamical

systems. The unstable regime is inherently transient and to analyze this regime we

characterize the response under the assumption of an exponential growth phase and a

subsequent decay phase until the system is brought back to the stable attractor. The

separation into a stable regime and unstable regime, allows us to capture the heavytailed statistics associated with intermittent instabilities. We illustrate the method

on three prototype intermittent systems and show that the analytical approximations

compare favorably with direct Monte Carlo simulations. We consider the following applications: an intermittently unstable mechanical oscillator excited by correlated noise;

a complex mode in a turbulent signal with fixed frequency, where nonlinear mode

interaction terms are replaced by a stochastic drag and additive white noise forcing;

and a stochastic Mathieu equation, featuring intermittent parametric resonance.

Thesis Supervisor: Themistoklis P. Sapsis

Title: Assistant Professor of Mechanical Engineering

iii

Acknowledgments

First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor Professor Themistoklis Sapsis

for his invaluable guidance and encouragement. I have learned a tremendous amount

from his supervision and this thesis would not have happened without his support.

I would like to acknowledge the Naval Engineering Education Center (NEEC

3002883706), the Office of Naval Research (ONR N00014-14-1-0520) for supporting

this research, and the Martin A. Abkowitz fund for a travel award. I thank the

American Bureau of Shipping for gracious support through a fellowship and also

support through a Pappalardo Fellowship made possible by A. Neil Pappalardo.

I thank all my friends here at MIT and around Cambridge and Boston, they have

made these last two years a pleasant and joyful experience. Last but not least, I thank

my parents and two sisters for their unconditional support and encouragement, no

words can describe how much gratitude I owe them.

iv

Contents

1

Introduction

1

2

Probabilistic description of intermittent systems

5

Problem statement and formulation . . . . . . . . . . . . .

5

2.2

Quantification of the stable regime

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

8

2.3

Quantification of the unstable regime . . . . . . . . . . . .

9

2.3.1

Stochastic description of the growth phase . . . . .

9

2.3.2

Stochastic description of the decay phase . . . . . .

10

Probability of the stable and unstable regimes . . . . . . .

11

.

.

.

.

Instabilities driven by Gaussian processes

13

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

13

3.2

Average time below and above the zero level . . . . . . . .

14

3.3

Distribution of time below the zero level

. . . . . . . . . .

15

.

.

3.1

.

3

.

2.4

.

2.1

4 Application to a parametrically excited oscillator

17

Problem formulation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . .

18

4.2

Probability distribution in the stable regime . . . . . . . .

. . . . .

19

4.3

Probability distribution in the unstable regime . . . . . . .

. . . . .

20

Asymptotics for the unstable probability distribution . . . . .

23

.

.

.

4.1

4.3.1

Envelope probability distribution in the stable regime . . .

. . . . .

26

4.5

Probability distribution for the velocity . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . .

27

4.6

Summary of the analytical results . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

.

.

.

4.4

v

29

4.7

5

6

. . . . . . . .

30

4.7.1

Comparison with Monte Carlo simulations . . . . . . . . . . .

32

4.7.2

Parameters and region of validity . . . . .... . . . . . . . . .

34

Discussion and comparison with numerical simulations

Application to intermittently unstable turbulent modes

39

5.1

Probability distribution in the stable regime . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

41

5.2

Probability distribution in the unstable regime . . . . . . . . . . . . .

42

5.3

Summary of the analytical results . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

44

5.4

Discussion and comparison with numerical simulations

. . . . . . . .

44

47

Application to the stochastic Mathieu equation

6.1

Problem definition and formulation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

49

Derivation of the slowly varying variables . . . . . . . . . . . .

51

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

53

6.1.1

6.2

Probability distribution for the slow variables

6.2.1

Stable regime distribution

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

54

6.2.2

Unstable regime distribution . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

54

6.3

Summary of the analytical results . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

56

6.4

Discussion and comparison with numerical simulations

. . . . . . . .

56

Conclusions and future work

59

A Gaussian Process Simulation

61

7

vi

List of Figures

2-1

An intermittently unstable system. The system (top) experiences a

large magnitude response when the parametric excitation process (bottom) crosses the zero level. Dashed green lines denote the envelope

of the process during the stable regime. The transient instability can

be described by two stages, an exponential growth phase and then a

subsequent decay phase that relaxes the response back to the stable

regim e. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3-1

8

Comparison of the analytic distribution PT(t) (3.6) with Monte Carlo

simulation, generated using 1000 ensembles of a Gaussian process with

correlation R(T) = exp(-r 2 /2) from to

=

0 to tf = 1000, for two

different sets of parameters: m = 5.0, k

k = 2.4 (right).

4-1

1.6 (left) and m = 5.0,

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

16

Scatter plot and contours of the joint pdf of T and A, for r= -2.08

(m = 5.00, k

=

2.40). Samples for A are drawn by inverse-sampling

the cumulative distribution function and samples of T are drawn from

realizations of a Gaussian process using 1000 ensembles of time length

t

4-2

=

1000. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Exact integral in equation (4.15) compared to the asymptotic expansion

given in equation (4.25), for a fixed uo and m

4-3

23

=

5.00, k = 2.00. .....

25

For the computation of the velocity pdf, we approximate the envelope

of the process during the extreme event with a harmonic function with

consistent period. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

vii

28

4-4 Sample realization (top) and the corresponding parametric excitation

process (bottom) demonstrating the typical system response during an

intermittent event for position (in thick blue) and velocity (in thin red)

for ri = -2.27 (k = 2.2, m = 5.0), c = 0.53. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4-5

31

Typical superposition of the stable (in dashed blue) and unstable (in

dotted red) part of the total probability law decomposition (2.6) of the

full analytical pdf.

4-6

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

32

Demonstration of the cusp phenomenon, which is prominent in regimes

with very frequent instabilities and/or instabilities of long duration, due

to approximations made in the unstable regime. . . . . . . . . . . . .

33

4-7 Analytic pdfs (4.41), (4.45) compared with results from Monte Carlo

simulations for position (left) and velocity (right), for parameters: k =

1.8, m = 5.0, c = 0.38, a. = 0.75.

4-8

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

34

Analytic pdfs (4.41), (4.45) compared with results from Monte Carlo

simulations for position (left) and velocity (right), for parameters: k =

2.2, m = 5.0, c = 0.53, o, = 0.75.

4-9

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

34

Analytic pdfs (4.41), (4.45) compared with results from Monte Carlo

simulations for position (left) and velocity (right), for parameters: k

2.6, m = 5.0, c = 0.69, a, = 0.75.

=

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

35

4-10 KL divergence for position (left) and velocity (right) between analytic

and Monte Carlo results for various values of damping (in terms of the

number of oscillations N after an instability) and k, which controls the

number of instabilities for a fixed m. For fixed m = 5.0. . . . . . . . .

5-1

Regime 1: Sample path (left) and analytic pdf (5.15) compared with

results from Monte Carlo simulations (right), for parameters: w

a = 0.5, m = 2.25, k = 2.0, L = 0.125.

5-2

37

=

1.78,

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

45

Regime 2: Sample path (left) and analytic pdf (5.15) compared with

results from Monte Carlo simulations (right), for parameters: w = 1.78,

a = 0.1, m. = 0.55, k = 0.50, L = 2.0. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

viii

46

5-3

Regime 3: Sample path (left) and analytic pdf (5.15) compared with

results from Monte Carlo simulations (right), for parameters: w = 1.78,

a- 0.25, m = 8.1, k = 1.414, L = 4.0.

6-1

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Oscillatory growth due to parametric resonance (left) for 6 > 0 and

exponential growth (right) when 6 < 0 of the Mathieu equation. . . .

6-2

46

48

Ince-Strutt diagram showing the classical resonance tongues (shaded)

for particular combinations of c and 6, for the Mathieu equation (6.1)

non-dimensionalized by Q. Transition frequencies at 6 = w /Q2

(n/2)2 . Stability boundaries are computed via Hill's infinite deteriminant [1). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6-3

Sample realization of the Mathieu equation (6.4) (top). The random

amplitude forcing term

#(t)

(bottom) triggers intermittent resonance

when it crosses above or below the instability threshold (dashed lines).

6-4

49

50

Comparison of Monte-Carlo results (6.25) (red curve) and analytic

results (6.24) of the Mathieu equation for various intermittency levels

with 6-4a being least intermittent and 6-4f most intermittent. ....

ix

58

Chapter 1

Introduction

A wide range of dynamical systems describing physical and technological processes

are characterized by intermittency. In other words, the property of having sporadic

responses of extreme magnitude when the system is "pushed" away from its statistical

equilibrium. This intermittent response is usually formulated through the interplay

of stochastic excitation, which can trigger internal system instabilities, deterministic

restoring forces (usually in terms of a potential) and dissipation terms. The presence of

intermittent instabilities can be identified by large amplitude spikes in the time series

of the system or heavy-tails in the probability density function (pdf) of the response.

It is often the case that, despite the high dimensionality of the stable attractor, where

the system resides most of the time, an extreme response of short duration is due

to an intermittent instability occurring over a single mode. This scenario does not

exclude the case of having more than one intermittent mode, as long as the extreme

responses of these modes are statistically independent. For this case, it may be possible

to analytically approximate the probabilistic structure of these modes and understand

the effect of the unstable dynamics on the heavy-tails of the response.

Instabilities of this kind are common in dynamical systems with uncertainty. One

of the most popular examples is modes in turbulent fluid flows and nonlinear water

waves subjected to nonlinear energy exchanges that occur in an intermittent fashion

and result in intermittent responses [2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]. Prototype systems that mimic

these properties were introduced in [9, 10, 11]. In recent works, it has been shown

1

that properly designed single mode models can describe intermittent responses, even

in very complex systems characterized by high dimensional attractors [11, 12, 13].

Another broad class of such systems includes mechanical configurations subjected to

parametric excitations, such as the parametric resonance of oscillators and ship rolling

motion [1, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18]. Finally, intermittency can often be found in nonlinear

systems that contain an invariant manifold that locally loses its transverse stability

properties, e.g. in the motion of finite-size particles in fluids, but also in biological

and mechanical systems with slow-fast dynamics [19, 20, 21, 22].

In all of these systems, the complexity of the unstable dynamics is often combined

with stochasticity introduced by persistent instabilities that lead to chaotic dynamics,

as well as by the random characteristics of external excitations. The structure of the

stochasticity introduced by these factors plays an important role on the underlying

dynamics of the system response. In particular, for a typical case the stochastic

excitation is colored noise, i.e. noise with a finite correlation time length. Due to

the possibility of large excursions by the colored stochastic excitation from its mean

value into an "unsafe-region," where instabilities are triggered, extreme events may be

particularly severe. Therefore, for an accurate description of the probabilistic system

dynamics, it is essential to develop analytical methods that will be able to accurately

capture the effects of this correlation in the excitation processes for intermittent modes.

However, analytical modeling in this case is particularly difficult, since even for lowdimensional systems, standard methods that describe the pdf of the response (such

as the Fokker-Planck equation) are not available or computationally too expensive.

For globally stable dynamical systems numerous techniques have been developed

to analyze extreme responses (see e.g. [23, 24, 25]). Various steps are involved that lead

to elegant and useful results, however the starting point is usually the assumption of

stationarity in the system response and this is not the case for intermittently unstable

systems. Extreme value theory [26, 27, 28, 29, 30] is also a widely applied method

that focuses on thoroughly analyzing the extreme properties of stationary stochastic

processes following various distributions. In this case, however, the analysis does not

2

take into account system dynamics and is usually restricted to very specific forms of

correlation functions [26, 27].

Approaches that place more emphasis on the dynamics include averaging of the

governing equations and variations thereof. However, the inherently transient nature

of intermittent instabilities makes it impossible for averaging techniques to capture

their effect on the response statistics. Other modeling attempts include approximation

of the correlated parametric stochastic excitation by white noise (see, for example

[31]

for an application to parametric ship rolling motion). However, even though this

idealization considerably simplifies the analysis and leads to analytical results, it

underestimates the intensity of extreme events, since instabilities do not have enough

time to develop (i.e., the system spends an infinitesimal time in the unstable regime,

which is insufficient for the system to depart from the stable attractor); in other words,

the original system, with colored excitation, has stronger more intense instabilities,

which a white noise idealization would fail to capture. For this case, heavy-tails can

be observed only as long as the parametric excitation is very intense, which for many

systems is an unrealistic condition.

In this thesis our goal is to describe and develop a fundamentally novel method

that will allow for the analytical approximation of the probability distributionfunction

(pdf) of modes associated with intermittent instabilities and extreme responses due to

parametric excitation by colored noise. This analytic approach will provide a direct link

between dynamics and response statistics in the presence of intermittent instabilities.

We decompose the problem by conditioning the system response on the occurrence

of unstable and stable dynamics through a total probability law argument. This idea

enables the separate analysis of the system response in the two regimes and allows us

to accurately capture the heavy-tails that arise due to intermittent instabilities. The

full probability distribution of the system state is then reconstructed by combining

results from the two regimes. We illustrate this approach on several prototype systems

with nontrivial statistics that arise in problems of turbulent flows, nonlinear waves,

and mechanics. We will thoroughly examine the extent of validity of the derived

approximations by direct comparison with numerical Monte Carlo simulations.

3

SL.

..

.

-

We emphasize that the new method we describe here offers vast computational

savings and accurate tail statistics. These two qualities, computational speed and

accurate tail statistics, are typically at odds with each other when we look at other

methods. For example, Fokker-Planck based methods become prohibitively expensive

when we are interested in tail statistics and require very accurate numerical methods

(since tail events have extremely low probabilities) to solve the resulting, usually high

dimensional, differential equations. The method described in this thesis overcomes

this contradictory condition (fast algorithm vs. accurate tails) by recognizing that tail

events are governed by different dynamics than the dynamics of the typical response.

Accordingly, we decompose the statistics in light of the fact that different dynamics

govern the two regimes, stable and unstable, and make appropriate approximations in

the two regimes to derive the response pdf for the system we are interested in. Here,

we are interested in deriving analytical results for the equilibrium pdf, and thus the

computational savings can be several orders of magnitude when we compare them

with, say, Monte Carlo results, which is the most accurate but the most expensive

technique.

4

Chapter 2

Probabilistic description of

intermittent systems

In this chapter we formulate our method for describing the probabilistic structure

of the response pdf for intermittently unstable dynamical systems. We begin from

a general dynamical system describing modes subjected to intermittent instabilities

and show how to apply the idea of a probabilistic decomposition by conditioning on

the two relevant dynamical regimes (stable and unstable regimes) through a total

probability law argument. This requires several components including determining

the conditional response pdf in the two regimes and also the probability of being in

the two regimes; we show to determine these quantities in an analytical framework.

The results from this chapter are the foundation for the applications we present in

later chapters.

2.1

Problem statement and formulation

Let (E, B, P) be a probability space, where

E is the sample space

with 6 E E denoting

an elementary event of the sample space, B is the associated --algebra of the sample

space, and P is a probability measure. We denote by Px the probability measure and

by Px the corresponding probability density function, if appropriate, of a random

quantity X. We are interested in describing the statistical characteristics of modes

5

subjected to intermittent instabilities. We consider a general dynamical system

=

G(x, t),

x ER ,

(2.1)

and assume that its response is an ergodic stochastic process. The analysis will rely

on the following additional assumptions related to the form of the intermittent instabilities:

Al The instabilities are rare enough that they can be considered statistically independent and have finite duration (localized).

A2 During an extreme event the influenced modes have decoupled dynamics. Moreover, for each one of these modes, the instability is the governing mechanism; i.e.,

nonlinear terms are not considered to be important during these fast transitions;

they are only considered to be important during the stable dynamics.

A3 After each extreme event there is a relaxation phase that brings the system back

to its stable stochastic attractor.

Under these assumptions we may express each intermittent mode, denoted by u(t; 0) E

R, where 0 E

e

(for notational simplicity, we drop explicit dependence on the proba-

bility space for random processes whenever clear), as a dynamical system of the form

,it + a(t; )u)+ E((U, v) = Ec(t; 0),

(2.2)

where F > 0 is a small quantity and ((u, v) is a nonlinear term (nonlinearizable), which

may also depend on other system variables v E R"'. Since E is a small quantity, we

can assume that the nonlinear term is important only in the stable regime. The

stochastic processes a(t; 0) and (t; 0) are assumed stationary with known statistical

characteristics. For a(t) we will make the additional assumption that its statistical

mean is positive a > 0 so that the above system has a stable attractor (we denote the

mean value operator, the ensemble average, by an overbar E). The above equation

can be thought of as describing the modulation envelope for a complex mode with a

6

narrowband spectrum, or one of the coordinates that describe the transverse dynamics

to an invariant slow manifold. As motivation, the model (2.2) can be thought as an

expansion of (2.1) in the form

,J= G((x2,

.,XN

-3)

Zaijxj + E bijXj, +

j,k

j

(aii + biix1 + b+X2 +

(2.4)

.

)xb+

+abx + ++ -bikXx

- , (2.5)

where we model excitations from other system variables as external noise ((t; 0),

quadratic interactions as parametric noise a(t; 0), and nonlinear terms are denoted

by(

The objective in this thesis is to derive analytical approximations for the probability distribution function of the system response, taking into account intermittent

instabilities that arise due to the effect of the stochastic process a(t). In particular,

these instabilities are triggered when a(t) < 0 and force the system to depart from

the stable attractor. Therefore, the system has two regimes where the underlying dynamics behave differently: the stable regime where a(t) > 0 and the unstable regime

that is triggered when a(t) < 0 (Figure 2-1). Motivated by this behavior, we quantify

the system's response by conditioning the probability distribution of the response on

stable regimes and unstable events, and reconstruct the full distribution according to

the law of total probability,

Ps(x) = Pa(x I stable regime)P (stable regime)+

Pu(x I unstable regime)P(unstable regime),

(2.6)

thereby separating the two regions of interest so that they can be individually studied.

The method we employ relies on the derivation of the probability distribution for each

of the terms in (2.6) and then the reconstruction of the full distribution of the system

by the total probability law. This idea allows us to capture the dramatically different

statistics that govern the system response in the two regimes. Essentially, we decouple

the response pdf into two parts: a probability density function with rapidly decaying

tails (typically Gaussian) and a heavy-tail distribution with very low probability close

to zero. In the following sections, we provide a description of the method involved for

the statistical determination of the terms involved in (2.6).

0

50

100

t

150

200

(t;)

15

instability triggered

5

0

0

50

100

150

200

Figure 2-1: An intermittently unstable system. The system (top) experiences a large

magnitude response when the parametric excitation process (bottom) crosses the zero

level. Dashed green lines denote the envelope of the process during the stable regime.

The transient instability can be described by two stages, an exponential growth phase

and then a subsequent decay phase that relaxes the response back to the stable regime.

2.2

Quantification of the stable regime

During the stable reginme we have by definition a > 0; therefore, under this condition

the considered mode is stable. Note that this condition is also true during the relaxation

(decay) phase after an extreme event when a switches to positive values a > 0, but

is not yet relaxed back to the stable attractor. To this end, we cannot directly relate

the duration of being on the stable attractor with the probability

(a > 0), but a

correction should be made. We present this correction later in Section 2.3.2. Here

we focus on characterizing the probability density function of the system under the

assumption that it has relaxed to the stable attractor, and, moreover, we have a > 0.

8

As a first-order estimate of the stable dynamics, we approximate the original

dynamical system for the intermittent mode by the stable system

t + dja>OU + &((u,v) =l(t;

0),

(2.7)

where MaI>o denotes the conditional average of the process a(t) given that this is

positive. The determination of the statistical structure of the stable attractor for (2.7)

can be done with a variety of analytical and numerical methods, such as the FokkerPlanck equation if the process

(t) is white noise (see, e.g., [32, 24]) or the joint

response-excitation equations otherwise [33, 34]. Using one of these methods, we can

obtain the probability distribution function for the statistical steady state of the

system, that is P (x Istable regime).

2.3

2.3.1

Quantification of the unstable regime

Stochastic description of the growth phase

In contrast to the stable regime, the unstable regime is far more complicated due

to its inherently transient nature. In addition, the unstable regime consists of two

distinct phases: a growth phase where a < 0 with positive Lyapunov exponent, and a

subsequent decay phase that starts when a has a zero upcrossing and is characterized

by a > 0 with negative Lyapunov exponent. We first consider the growth phase, where

we rely on assumption A2, according to which the dominant mechanism is the term

related to the instability. Under this assumption, the first-order approximation of the

dynamics during the growth phase is given by

,it + a(t; 0)u = 0,

(2.8)

where no is a random initial condition described by the probability measure in the

stable regime, T is the random duration of the downcrossing event a < 0, and A is

the random growth exponent, which for each extreme event, due to the rapid nature

9

of the growth phase, can be approximated by

A ~

a(t; 0) dt,

(2.9)

where t* represents the time of the start of the instability and r the duration that

a < 0. This implies the following representation for instabilities during the growth

phase

'u(t; 9) = uoeT,

(2.10)

and therefore

P(U > U* I a < 0) = P(UoeAT > u* I a < 0)

= P(uoeAT > U* I a < 0, uo) P(uo),

(2.11)

where u* is the value of the response we are interested in. The right-hand side of (2.11)

is a derived distribution depending on the probabilistic structure of A and T. The

initial value uO is a random variable with statistical characteristics corresponding to

the stable regime of the system, in other words by P(u I stable regime). Hence, to

determine the required probability distribution we need only to know P(a, T Ia < 0),

i.e., the joint probability distribution function of a (given that this is negative) and

the duration of the time interval over which a is negative. This distribution involves

only the excitation process a, and for the Gaussian case it can be approximated

analytically (see Section 3). Alternatively, one can compute this distribution using

numerically generated random realizations that respect the statistical characteristics

of the process.

2.3.2

Stochastic description of the decay phase

The decay phase is also an inherently transient stage. It occurs right after the growth

phase of an instability, when a has an upcrossing of the zero level, and is therefore

characterized by positive values of a, and drives the system back to the stable attractor.

10

6

9

1

--

Au6vw

To provide a statistical description of the relaxation phase, we first note the strong

connection between the growth and decay phases. In particular, as shown in Figure 21, for each extreme event there is a one-to-one correspondence for the values of the

intermittent variable a between the growth phase and the decay phase. By focusing

on an individual extreme event, we note that the probability of u exceeding a certain

threshold during the growth phase is equal with the probability of u exceeding the

same threshold during the decay phase. Thus over the total instability we have

P(n > u* I unstable regime) =

P(u > u* I instability - decay) = P(u > u* I instability - growth),

(2.12)

where the conditional distribution for the growth phase has been determined in (2.11).

2.4

Probability of the stable and unstable regimes

In the final step we determine the relative duration of the stable and unstable regimes.

To do so, we rely on the ergodicity of the system response. This allows us to quantify

the probability of a stable and an unstable event in terms of their temporal durations.

The probability of having an instability is not simply P(a < 0), because of the decay

phase the duration of an instability will be longer than the duration of the event a < 0.

To determine the typical duration of the decay phase, we first note that during the

growth phase we have

Up =

oe"I <OT.<,

(2.13)

where Ta<o is the duration for which a < 0 and up is the peak value of u during the

instability. Similarly, for the decay phase we utilize system (2.7) and obtain

nO=

upe-Zila>oTdecay

11

(2.14)

......................

...............

Combining the last two equations (2.13) and (2.14), we have

Ta<o

-610y>0

Tdecay

dIO<O

(2.15)

The equation above (2.15) expresses the typical ratio between the growth and the

decay phases. Thus, the total duration of an unstable event is given by the sum of

the duration of these two phases

Tinst

(I -

(2.16)

l'>O) Ta<O.

Using this result, we can express the total probability of being in an unstable regime

by

P(unstable regime) = (1 -

I'>O) P(a < 0).

(2.17)

Note that since we have assumed in Al that instabilities are sufficiently rare so that

instabilities do not overlap and that instabilities are statistically independent, we will

always have P(unstable regime)

< 1. Hence, the corresponding probability of being

in the stable regime is

P(stable regime) =1 - (I - T ">)

12

P(a < 0).

(2.18)

Chapter 3

Instabilities driven by Gaussian

processes

In this chapter we recall relevant statistical properties associated with Gaussian processes. First, we define what is a Gaussian processes, and then describe important

statistical quantities associated with a Gaussian excitation mechanism; that is, systems where instabilities are driven by Gaussian processes. In particular, we note the

importance of the zero-level of a(t) in the dynamical system (2.2). This threshold level

is critical since it defines the boundary between a stable and an unstable response. We

quantify the following statistical properties associated with the zero-level of a Gaussian excitation process: the probability that a(t) is above and below the zero-level,

the average duration spent below the zero-level, and the probability distribution of

the length of time intervals spent below the zero-level. These important quantities

will be used in future chapters, where we assume a stationary Gaussian excitation

mechanism.

3.1

Introduction

A stochastic process is said to be Gaussian if all of its finite-dimensional distributions

are normal. In other words X(t), where t E R is said to be Gaussian if for any choice

13

of n and t1, . .

,t

E R we have

X

(3.1)

X.)~ N(p, E),

(X,.

for some expectation vector ti and covariance matrix E. Gaussian process are completely determined by their expectation function p(t) = E(X(t)) and covariance

function R(s, t) = Cov(X(s), X(t)). Furthermore, a Gaussian process is said to be

stationary if its expectation function p(t) is constant and its covariance function is

invariant under translations in time, i.e. R(T) = Cov(X(t), X(t +

T)).

In addition,

an important property associated with R(r) is its relation with the so-called power

spectral density function of X(t),

Rx(T)

J

Sy(w)e

' dw.

(3.2)

-00

By the Wiener-Khintchine theorem, the functions R(r) and S(w) form a Fourier transform pair. Algorithms for simulating Gaussian processes can be found in Appendix A.

We consider the case where a(t) is a stationary Gaussian process with mean m and

variance k 2 , and for convenience write a(t)

m. + ky(t), so that -y(t) has zero mean

and unit variance. Therefore, the rare event threshold, in terms of the process -(t), is

given by i = -mn/k.

We assume that second order properties, such as the correlation

function or power spectral density function, for a(t) are known. In addition, we denote

by 0 ( -) the standard normal probability density function and by <D( -) the standard

normal cumulative probability density function. Since 7(t) is a stationary Gaussian

process, the probability that the stochastic process is in the two states IP(a < 0) and

IP(a > 0) is ]P(- <'1)

3.2

=

41(q) and P(' >

j)

1 - 4b(q), respectively.

Average time below and above the zero level

Here we determine the average length of the intervals that a(t) spends above and

below the zero level. For the case a(t) < 0, that is y(t) < i, the expected number of

14

1

11,1111"'."11111,11,1

....

............. I, .....

upcrossings of this threshold per unit time is given by Rice's formula [35, 36] (for a

stochastic process with unit variance)

-R

)uP ( , ') d"(

0( ) exp(-4 2/2),

(3.3)

0

where N+ (ij) is the average number of up crossings of level q per unit time, which is

equivalent to the average number of downcrossings N (,j), Py is the joint pdf of y

and its time derivative

, and the primes denote differentiation. The expected number

of crossings is finite if and only if -y(t) has a finite second spectral moment [36].

The average length of the interval that 7(t) spends below the threshold

j

can then

be determined by noting that this probability is given by the product of the number

of downcrossings of the threshold per unit time and the average length of the intervals

for which 'y(t) is below the threshold q [37]

- P( < q)

(q)

Tao =

(3.4)

Hence, using the result (3.3), we have

Ta<00) = 27r exp(?2 /2)<()

"(0)

3.3

(3.5)

Distribution of time below the zero level

Here we recall a result regarding the distribution of time that the stochastic process

7(t) spends below the threshold level r, that is the probability of the length of intervals

for which -y(t) < q.

In general, it is not possible to derive an exact analytical expression for the distribution of time intervals given 'y(t) < q, in other words the distribution of the length of

time between a downcrossing and an upcrossing. However, the asymptotic expression

in the limit il -+ -oo is given by [37] (henceforth we denote Ta<o by T for simplicity)

15

-

wt

PT(t) -T 2 exP(-wt2/4T ),

2T

(3.6)

2T2 /ir, where T is given

which is a Rayleigh distribution with scale parameter

by (3.5). This approximation is valid for small interval lengths t, since the derivation

assumes that when a downcrossing occurs at time t1 only a single upcrossing occurs

at time t2

= t1

+ t, neglecting the possibility of multiple crossings in between the

two time instances. In Figure 3-1 the analytic distribution (3.6) is compared with

numerical results, and as expected, we see that the analytic expression agrees well

with the numerical results for small interval lengths, where the likelihood of multiple

upcrossings in the interval is small. In addition, note that the only relevant parameter

of the stochastic process -y(t) that controls the scale of the distribution in equation (3.6)

is the mean time spent below the threshold level, which depends only on the threshold

rj and R"(0).

101

101

- -

Monte Carlo

10

10

10

10

10o2

10 -2

10

10

0

10

numeric mean 0.744

analytic mean = 0.737

1

0

1N0

-4

10-41

1

-Analytic

- Monte Carlo

-Analytic

2

3

t

4

5

6

10 0

7

numeric mean 1.03

analytic mean = 1.02

1

2

3

4

5

6

Figure 3-1: Comparison of the analytic distribution PT(t) (3.6) with Monte Carlo

simulation, generated using 1000 ensembles of a Gaussian process with correlation

R(r)

m

=

exp(-r 2 /2) from to = 0 to tf = 1000, for two different sets of parameters:

5.0, k = 1.6 (left) and m = 5.0, k = 2.4 (right).

=

16

7

Chapter 4

Application to a parametrically

excited oscillator

In this chapter we consider parametrically excited motions. In parametrically excited

systems, excitations appear in the governing differential equations as time varying

coefficients. We are interested in the realistic case of stochastic or random parametric excitations, which can lead to transient instabilities or transient resonances. We

consider systems described by

X +

cx +

K(t)X

=

(t),

(4.1)

where K(t) is in general a time correlated stochastic parametric excitation process,

i.e. colored noise, and

(t) is additive noise, which may also be time correlated. In

Chapter 6 we discuss the intermittent resonance case, whereby even a small amplitude

parametric excitation can produce a large response. Here we focus on parametric

excitations the lead to transient instabilities. In this case, intermittent instabilities

are triggered due to large excursions of the parametric excitation process K(t) into the

region K < 0. We consider this as a rare problem, namely that these large excursions

occur with relatively low probability, and consequently the instabilities they trigger

are rare events, so that on average - > 0 and the response is stable.

17

Parametrically excited systems arise in many areas of engineering and physics.

We mention but a few examples of physical systems where the governing differential

equation is parametrically excited (see e.g. [38, 39, 1, 24] for additional examples and

further details), they include: the transverse motion of elastic beams excited axially;

electrical circuits, such as LC circuits (inductor connected to a capacitor in series)

with time varying capacitance [40]; the motion of pendulums, including cases where

the support is excited or the length of the rod is time varying; the transverse vibration

of a taut strings undergoing variations in tension or torsion [41].

A particularly important example in ocean engineering is ship roll motion in the

presence of random waves [31, 17, 423. Here random restoring forces, due to the action

of irregular water waves, show up as parametric terms in simplified models describing the ship's roll response. The possibility of indirectly excited large-amplitude roll

motions are a serious threat to the safety of a ship and human life. This requires

understanding the action of stochastic terms and nonlinearity in the governing equations of motion. Several models and methods have been proposed in connection with

the problem to predict large roll motions and capsizing probabilities, where we are

pressed by the need for easy to use analytical results and inexpensive computational

methods [43, 44, 45, 46, 47]. Nevertheless many deficiencies in various methods and

models remain owing to the challenges associated with capturing the effects of the

correlated nature of real ocean waves and system nonlinearities and, most importantly,

quantifying the resulting non-Gaussian response statistics. The results here (see also

Chapter 6) offer a novel strategy for efficiently quantifying large roll motions in an

analytical setting, and is able to capture the effect of the correlated nature of real

ocean waves.

4.1

Problem formulation

With the presentation of the method in Chapter 2, we now proceed to our first application. We consider the following single-degree-of-freedom oscillator, under parametric

18

..............

stochastic excitation and additive white noise forcing,

z(t) + czt(t) +

ii(t;

)x(t) = oXW(t; 0),

(4.2)

where c is damping, K(t) is a stationary Gaussian process of a given power spectrum

SK(w) or correlation function R,(r) with mean m and variance k 2 , and W(t) is white

noise with amplitude or. Here 77

--m/k defines the extreme event threshold. We

can alternatively write equation (4.2) in state space form as

dx 1

(4.3)

=x2 dt

dx 2 = -(cx2 +

K(t)x1)

dt

+ o-x

(4.4)

dW(t).

The presentation will follow Chapter 2, although the analytical expressions for the

pdf is computed directly for position and velocity (instead of the envelope process

u) for instructive purposes. At the end of this chapter we present comparisons with

direct numerical simulations and thoroughly examine the limits of validity for the

approximations we have made.

4.2

Probability distribution in the stable regime

We first derive the probability distribution for (4.2) given that the system is in the

o. This

stable regime. Following Section 2.2, we replace K(t) by the mean W 2

K

approximation is valid since only small fluctuations of the process

around the

K(t)

mean w occur in this state, and these fluctuations have a minor impact on the system's

probabilistic response. Making this approximation, (4.3) becomes

:z(t) + cg(t) + w2x(t) = Uo-W(t).

(4.5)

To determine the mean w., note that its probability density function is given by

P, (x I r

> 0)

k (I 19

k

<(())

(4.6)

..............

and thus

2

WS

Re~

m+ k

OW___

.)n

(4.7)

The density in the stable regime can now be found by seeking a stationary solution

of the Fokker-Planck equation of the form P(xI, X2) = P(H), where H =

(W x + x2)

is the total mechanical energy of the system. In this case the Fokker-Planck equation

simplifies to [24]

1 dP

=0

cP(H)+-o

2 dH

> P(H)=qexp

2

2 H

ar

(4.8)

where q = cw,/(7ro-x) is a normalization constant. Taking the marginal with respect

to X2 gives the probability density for the system's position

P.,(x I stable regime) =

which is Gaussian with variance o 2 =

a/

exp

.5

-x

2

(4.9)

(2cW2). Similarly, taking the marginal with

respect to x, gives the probability density for the system's velocity

P, (x Istable regime) =

cc

2 exPy

2 2

,

(4.10)

where the variance is o 2 = o /(2c).

4.3

Probability distribution in the unstable regime

Here we derive the probability distribution for the system's position x, during the

growth stage of an instability. In the unstable regime, the system initially undergoes

exponential growth due to the stochastic process ri(t) crossing below the zero level,

which is the mechanism that triggers the instability. After a finite duration of exponential growth, which stops when K(t) crosses above the zero level, and due to the

large velocity gradients that result, friction damps the response back to the stable

attractor. Following assumption A2, we consider the parametric excitation as the

20

primary mechanism driving the instability during the growth phase, and therefore

ignore the effect of friction during this stage of the instability.

We treat the system response as a narrowbandprocess. This means that the response

has a spectrum that is narrowly distributed around a mean frequency, i.e., q = u-,/w. <

1, where w, = f wS(w) dw and o-

f(w

-

w,) 2S(w) dw [48]. We can therefore describe

the instability in terms of the envelope u for the position variable by averaging over the

fast frequency w,. During the growth phase we have u ~ uoeAT where uo is the random

value of the position's envelope before an instability (to be determined in Section 4.4),

T is the random duration of the event s < 0, and A is the random growth exponent,

which will be the same for both the position and the velocity variables. Substituting

this representation into (4.2), we find A2 + ~ 0,- so that the positive eigenvalue is

given by A ~

-

.

To proceed, we set u = uoeAT and y = A; then, from a change of

variables,

Psy(u, y) = PAT(A, t) Idet[0(A, t)/0(u, y)]

,

(4.11)

where we understand that the pdf is conditional upon K < 0 and uO. Next we assume

that T and A are independent (see Figure 4-1) and thus we have

PA(A)P(t)

Py (U, Y) = PA(At)

uO Aexp (At)

_____/__

_1

uy

PA (Y)PT (

u > iUo, y > 0.

y

(4.12)

Taking the marginal density gives

Pu(u) =- J-PA(y)P T (lo(/UO)) dy.

U I0 y

Now, since P(A) = P(\

PA(A)

-

(4.13)

y

< 0) from another change of variables we obtain

-l,

2A

<41r0)

2)

P(-A2( -

A 2 + in

(4.14)

k

k~lb(,q) (

2A

) A>0,

since P(K.) is normally distributed. Combining this result and the fact that PT is given

by the Rayleigh distribution (3.6), with (4.13) gives the final result for the probability

21

....... MMMMM-'-"-

density function

I K < Oo)

y2 +m)

7log(u/uo) 71

kT

<(r)

k

I0 y

x exp

-

I2

4T2y2

log(U/uo)2

dy,

It > Ito,

(4.15)

where T is given in (3.5). Moreover, utilizing the expression for the duration of a

typical extreme event (2.16), we have

Tinst

1

(4.16)

+ 2XAo TK<O,

where for the relaxation phase we have the rate of decay for the envelope being -c/2.

To formulate our result in terms of the position variable, we refer to the narrowband

approximation made at the beginning of this analysis. This will give approximately

x, = I cos W, where

'p

is a uniform random variable distributed between 0 and 27r.

The probability density function for z = cos ' is given by Pz(x) = 1/(7/w

XC

1

-

x2),

[-1, 1]. To avoid double integrals for the computation of the pdf for the position

variable, we approximate the pdf for z by P2 ( x)

=

-(6(x + 1) + 6(x - 1)). This will

give the following approximation for the conditionally unstable pdf:

1

P,(x I K < 0, uo) = -P(Ix I K, < 0, uo).

2

(4.17)

We note that as presented in Section 2, the pdf for the envelope u may also be

used for the decay phase. However, during the decay phase the oscillatory character

(with frequency w,) of the response has to also be taken into account. Nevertheless, to

keep expressions simple we will use equation (4.17) to describe the pdf for the position

in the decay phase as well. We will show that this approximation compares favorably

with numerical simulations.

22

-

3

2.5

2,

1

-

0.50

0

6

5

4

3

T

2

1

-2.08

Figure 4-1: Scatter plot and contours of the joint pdf of T and A, for r=

cumulative

(M = 5.00, k = 2.40). Samples for A are drawn by inverse-sampling the

distribution function and samples of T are drawn from realizations of a Gaussian process

using 1000 ensembles of time length t = 1000.

4.3.1

Asymptotics for the unstable probability distribution

In the spirit of keeping our final expressions simple, here we derive an asymptotic

expansion for the integral (4.15) that describes the distribution for the position's

envelope during the growth phase of an instability, as u -4 oo, treating 1 0 as a

parameter. For convenience in (4.15) let PL(tu

7 log(a/ao)

((u, y; uo) =2

v/2wkT <b(rj)uy

7r log(a//uo)

=

2wkt2

V 27kT

(

exp

x < 0, < o) = Jo (u, y; 0o) dy, that is,

(y 2 + r)

2

~

2k

2

7r

-2

4T y

2

o1y/ao)

(4.18)

(4.19)

exp(O(u, y; 'uo)),

u{)

2

<b(,q),ty

where O(u, y; ao) denotes the terms being exponentiated (we suppress the explicit

dependence on the parameter

0o

,-No

P

,(

<0,ao) /(U, Y; -o) dy =2

0

for convenience). In other words

7rlog(U/Uo)

J - exp(O(u, y)) dy. (4.20)

V 27rkT <bguoy

0_

This integral can be approximated following Laplace's method, where in this case we

have a moving maximum

[49]. For fixed u the exponential is distributed around its peak

23

value y* = maxy exp(0(u, y; no)), so that we may make the following approximations

to leading order

ir log(u/uo)

f(y

1

YrF

-2U

P,(u I V < 0, Uo) ~

exp O(u, y*) +

,I

y

v'2-7ikT <(n)u

y*)2

-

2

dy

YO(u, y*) +

2

(4.21)

J

(u, y*; Uo)

0

exp

(Y -

2

*)T

YY)O(U, Y*) +..-) dy

(4.22)

-00

C

where

(4.23)

(U, y*; O)

a is a normalization

constant that is computed numerically. In order to arrive

at a closed analytic expression for y* = maxy exp(O(u, y)), we find that the following

expression is a good approximation for y* (see the note at the end of this section for

details):

/r

y*(U; Uo) =

2

1/4

-2

log(qU/O) 1/ 2,

m 2 > k2.

(4.24)

\4mT

Hence, we have the following expression that approximates the original integral:

1

P(u

IK <

0, 'O)

C

((u, y* uo),

m 2 > k2 .

(4.25)

In our case the assumption is that instabilities are sufficiently rare that the standard

deviation k of the Gaussian process K(t) will be smaller than its mean m, and the

condition m 2 >> k 2 in (4.25) will be satisfied. Indeed, the derived asymptotic expansion (4.25) and the exact integral (4.15) show excellent agreement, even for small

values of u (see Figure 4-2).

Note

Here we provide some details regarding the asymptotic expansion. According

to Laplace's method, this integral will be distributed near the peak value of the term

being exponentiated:

(y2 +2 rn) 2

(XY;XO

2k2

(xy;o) -

24

_

__

4T 2y2

log(X/o)

2

.

(4.26)

Exact

100

-- Asymptotic

10

102

103

)

2

4

6

U

10

8

Figure 4-2: Exact integral in equation (4.15) compared to the asymptotic expansion

given in equation (4.25), for a fixed no andm = 5.00, k = 2.00.

To find the maxima y* = max, exp(9(x, y; x 0 )), we differentiate (4.26) with respect

to y:

y2

--- 2y -+

+

0

k2

-+

(4.27)

2Tr log(x/xo) 2

.

ay

2T 2y3

To arrive at a closed form analytic approximation for y*, we must determine the relative

order of magnitude of y. To this end, investigating the terms in the integral in (4.13),

we note that the maximum ymx of PA(y) will determine the order of magnitude of y,

d

-P(y)

2w exp

(y 2 + n)2

dy k4b(rn)v/-2-

-

dy

2k2

0

)m)

-> 2y4 + 2mny2 - k 2 = 0;

thus if m 2 > k 2 , to leading order yka

(4.28)

~ k 2 /2m so that y 2 ~ O(k 2 /"n). Using this

result, we may approximate (4.26) by

2T2

log(XXO)

z-

2

y*(X; XO) = ( rk2

4rk-2

25

1/4

log(x/xo)1/

2

,

k2

)

y

M2

>> k2 . (4.29)

4.4

Envelope probability distribution in the stable

regime

In the derivation of the probability density in the unstable regime we conditioned

the result on the initial value of the position's envelope right before an instability

occurs. The stable regime's envelope is defined as the locus of local maxima of the

stationary Gaussian process that governs the system before an instability. For a

stationary Gaussian process of zero mean the joint probability density of the envelope

and the envelope velocity is given by [50]

P(-it) =

(liu

a

exp 2

qAo 2wA2

2

it 2~

_+

qA 2

Ao

,

(4.30)

where A, is the nth order spectral moment for the one-sided power spectral density

of x, in the stable regime and q 2 =1 - A2/AOA 2 describes the extent to which the

process is narrowbanded. In our case, we are interested in the pdf of the envelope for

the position P(uo); marginalizing out it from (4.30) gives

00

P(u, it) du

P(u)

exp(-u 2 /2Ao),

(4.31)

-00

which is a Rayleigh distribution with scale parameter v/\O. The zeroth-order spectral

moment is the variance of the Gaussian pdf in (4.9), i.e. A= o/(2cW2), and thus

2cw x

PU(x) =

2

exp(-cw x 2 /or ).

(4.32)

The pdf above determines the distribution of the initial point of the instability uo.

We use this result to marginalize out uO from the pdf of the unstable distribution

derived in Section 4.3, which was conditioned on a fixed initial point of an instability.

26

.

..

............

.....................................

Using (4.17) and (4.25) this gives the final result for the density in the unstable regime:

(X I K < 0)

1 P(xl (I <0, uo)P 0 (uo) duo

=

(4.33)

2

J((Ix1, y*(IxI;uo); uo)Pu(uo) duo,

=

(4.34)

0

In other words,

Px1 (x I unstable regime)

-

J

, y*(|xI; 'o); uo)Ps0 C(o) duo.

(4.35)

0

4.5

Probability distribution for the velocity

The probability density for the system's velocity x 2 in the stable regime can be found

by marginalizing the solution obtained from the Fokker-Planck equation (4.10). The

same result may be obtained by relying on the narrowband property of the stochastic

response in the stable regime. In particular, we may represent the stochastic process

for position x1 in terms of its spectral power density [25]

00

J= cos(Wt + (w)) 2Sx(w) dw,

X

(4.36)

0

where the last integral is defined in the mean square sense. Differentiating the above,

we obtain

00

w cos(wt + W(w) +

X2

2Sx(w) dw

(4.37)

0

00

cos(wt + y(w) + 2 V)2Sx(w) dw,

ws

(4.38)

0

using the narrowband property of the spectral density around W,. Note that the

integral in the last equation has the same distribution as x1 . Thus, it is easy to prove

that the probability density function of x 2 in the stable regime is given by the pdf of

WsX1.

27

In the unstable regime stationarity breaks down, and the envelope of the stochastic

processes describing position changes with time. This has an important influence on the

probabilistic structure for the velocity, which cannot be approximated as it was done

in the stable regime. The reason is that we have an additional time scale associated

with the variation of the envelope of the narrowband oscillation (see Figure 4-3). For

the purpose of computing the pdf for velocity in the unstable regime, we approximate

the envelope for position during the instability by a sine function with a half-period

equal to the average duration of the extreme events (4.16): Tilst

(1 + 2A,<o/c)Tco.

This gives the following approximate expression for the unstable regime:

'11=) sin(wat)

J

cos(wt + O(w))

(4.39)

2Sx(w) dw,

0

where up/uO is the ratio of the extreme event peak value for the envelope over the

initial value of the envelope (before the extreme event), and w,, =r/TiSt. Assuming

that up/uo >> 1 we have that the pdf for velocity during the unstable regime is also

given in terms of x 1 but with the different scaling factor

X2

+(

S+ - -X1.

2(

1 (4.40)

(1 + 2A.,scO/c)T)

The last relation gives a direct expression for the pdf of velocity in the unstable regime.

Using this scaling factorwi,,t --- (w, + wu)/2 for the conditionally unstable pdf and

the correct scaling for the stable regime w., we can derive an approximation for the

pdf of velocity (given in Section 4.6).

5- (t;O)

0 -----5 -0

50

100

t

150

200

Figure 4-3: For the computation of the velocity pdf, we approximate the envelope of

the process during the extreme event with a harmonic function with consistent period.

28

4.6

Summary of the analytical results

Combining the results of equations (4.9),

Probability distribution for position

(4.35), and (4.16) according to the law of total probability (2.6) gives the following

heavy-tailed, symmetric probability density function for the position:

P,, (x) =(i

exp

(1 + 2A,~o/c)+('q))

-

2x

-

2

1~

xCE R.

(4.41)

x2 dxo.

(4.42)

z)do

o;z)a

(xy(x

+ (1 + 2Xc/)()

0

Writing each term explicitly, we have

- (y*(Ix;x

x exp

j

(I ) f

VIcw 2

2

2i6or kT

o) 2 +-M)

2

2k2

Probability distribution for velocity

_

log(XI/XO)

o

(|x|/XO)y* (|~X O)

/

+ (1 + 2XA<o/c)I(q)

x2

exp

P, (x) = (1 - (1+ 2Ax,<O/c)())

log(|IX/xo)

2

_.

4T2y*(Ix;XO) 2

cw! 2

02

To obtain the pdf for velocity we scale the

probability distribution function for the position in (4.41). As noted in Section 4.5,

the correct scaling for the first term in (2.6), which represents the stable regime, is

given by w,, and for the second term, for the unstable regime, the scaling is given by

Winst.

Applying the random variable transformation P, (x) = P, (x/w)/w with the

appropriate scaling for each of these two terms yields

P 2 (x) =(i

-

(1 + 2AX

IXI/win~t

/c)i()

C exp(-

+ (1 + 2A,.<o/c)()

1

winst x )o ) no (xo

x wist

X

f

x)

2winstc

29

x,

xER. (4.43)

For the integral in the second term in (4.43), making the substitution xo

winst',

we have

w2

PX2(X IK< 0)=2u~T24

2

2

log(xf/xo)

(Ixl/xo)y*(IxI; Xo)

s

k0)20

x exp((Y*(IXI;

J

lxi

i7c

2

7 log( XIXO) 22 CW2 2

o2

+)2

2k2

4T y*(IxI; XO)

dx0. (4.44)

w;n2

Therefore, rewriting (4.43), gives the following pdf for velocity:

P2 (x)

C exp -C

(1 - (1 + 2AK<o/c)4b('r)

x2

lxi

+ (1 + 2Aso/c)<(r)

2

-

(xl, y*(xI; xo); xo)P,0 (xo/wi.t) dxo,

(4.45)

where the integral in the second term is explicitly given in (4.44).

4.7

Discussion and comparison with numerical simulations

Here we discuss the analytic results for the system response pdf given in Section 4.6,

present comparisons with Monte Carlo simulations, and describe the effect of varying

system parameters on the analytical approximations. In addition, we examine the

region of validity of our results with respect to these parameters.

First, in Figure 4-4 a sample system response is shown alongside the corresponding

signal of the parametric excitation. This sample realization is characteristic of the

typical system response for the case under study (rare instabilities of finite duration).

During the brief period when K(t) < 0, at approximately t = 85, the system experiences

exponential growth and when the parametric excitation process V.(t) returns above

the zero level, friction damps the system response from growing indefinitely, returning

the system to the stable state after a short decay phase.

30

-position-velocity

5-

0

-5

0t

40

60

80

60

80

t

100

12

1401TT-

100

120

140

10

5-

0 ----------------------40

60

----------------- ~~--- -- ~-100

80

120

140

Figure 4-4: Sample realization (top) and the corresponding parametric excitation

process (bottom) demonstrating the typical system response during an intermittent

event for position (in thick blue) and velocity (in thin red) for rj = -2.27 (k = 2.2,

m - 5.0), c = 0.53.

In Figure 4-5, a typical decomposition of the stable and unstable parts of the full

response pdf is presented. We emphasize that the tails in the system response pdf

for

are completely described by the term in the total probability law that accounts

in the

system instabilities, whereas the inner core of the pdf is mainly due to the term

total probability decomposition that corresponds to the solution in the stable regime.

Despite the fact that the system spends practically all of its time in a stable state,

the stable part in the expression for the response pdf contributes essentially nothing

to the tails of the distribution. The tails, in other words, completely account for the

statistics of system instabilities, which are highly non-Gaussian and are described by

a fat-tailed distribution.

The analytical results for the system response pdf given in (4.41) and (4.45) have

been derived under a careful set of assumptions. We observe that if the frequency

of instabilities is large or if damping is weak (i.e., extreme events of long duration),

pdf

or if there is any parameter combination such that the conditionally unstable

in the total probability decomposition (2.6) contributes significantly to the stable

state, then our analytical results will likely overestimate the probability near the

31

-Full

solution

-- Stable part

Unstable part

100

10

10

10-4

-6

-4

0

x

-2

2

4

6

Figure 4-5: Typical superposition of the stable (in dashed blue) and unstable (in dotted

red) part of the total probability law decomposition (2.6) of the full analytical pdf.

Gaussian core and underestimate the tail probabilities. This behavior is expected,

since our assumptions are no longer strictly valid. If this is the case, a cusp near the

mean state may be observed in our analytical expressions for the pdf, which is due to

the approximation made in Section 4.3, where we derive the conditionally unstable

pdf for the position variable in terms of its envelope (4.17) (see Figure 4-6). This

phenomenon is more pronounced in the pdf for the velocity x 2 , since the unstable part

of the decomposition (2.6) is scaled by a frequency that is smaller than the stable

part, which pushes more probability toward the Gaussian core. A minor contributing

factor to the severity of this cusp is due to the integral asymptotic expansion made in

Section 4.3.1; the asymptotic expression in (4.25) displays sharper curvature near uo

when compared to the exact integral in (4.25), resulting in a slightly more pronounced

cusp.

4.7.1

Comparison with Monte Carlo simulations

Here we compare the analytic approximations in (4.41) and (4.45) with Monte Carlo

simulations, when the stochastic parametric excitation

32

(t), with mean m and standard

*~0

10

10

-

- Full solution

Stable part

--

. Unstable part

Unstable part

10101

102

-8

-6

4

2

0

2

4

-2

8

6

-1.5

-1

-0.5

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

Figure 4-6: Demonstration of the cusp phenomenon, which is prominent in regimes with

very frequent instabilities and/or instabilities of long duration, due to approximations

made in the unstable regime.

deviation k, is given by an exponential squared correlation function of the form

R(T)= exp(-T 2

/2).

We solve (4.3) using the Euler-Mayaruma method [51], from to

-

0 to tf = 200

with step size At = 2-. Realizations of the Gaussian process K(t) are generated

according to an exact time domain method

following values for the system parameters: a.

[52]. To preform simulations we fix the

= 0.75, m

5.00. For the results in this

subsection, we furthermore fix the value of friction at c = 0.38, which corresponds to an

average of a single oscillation during the decay phase of an instability. Moreover, for this

subsection, samples after 20 computational steps are stored and used in calculations,

and 5000 realizations are used for k

=

1.8 and 2500 realizations otherwise. In Figs. 4-

7, 4-8, and 4-9 Monte Carlo results for the pdf for position and velocity are compared

with the analytic results given in (4.41) and (4.45) for various k values, which controls

the mean number of instabilities for fixed m through the parameter rY. Observe that the

analytical pdf for position and velocity match the results from Monte Carlo simulations

for both extreme events and the main stable response, capturing the overall shape and

probability values accurately (the figures for position are plotted out to 50 standard

deviations of the stable Gaussian core).

33

-- Monte Carlo

Carlo.

100 -Monte

-Analytic

100

-- Analytic

10-2

10

-

10-

-

10

10

-15

-5

-10

0

X

-30

15

10

5

-20

-10

30

20

10

X0

Figure 4-7: Analytic pdfs (4.41), (4.45) compared with results from Monte Carlo

simulations for position (left) and velocity (right), for parameters: k = 1.8, m = 5.0,

c = 0.38, o-x = 0.75.

-- Monte Carlo

-Analytic

-- Monte Carlo

-

10

-Analytic

10-2

102

10-4

10

10

-4

20

10-6

10-61

-5

-10

0

5

-20

10

-10

0

X

10

20

Figure 4-8: Analytic pdfs (4.41), (4.45) compared with results from Monte Carlo

simulations for position (left) and velocity (right), for parameters: k = 2.2, m = 5.0,

c = 0.53, a-= 0.75.

4.7.2

Parameters and region of validity

Here we quantify the effect of varying system parameters on our analytical approximations. In particular, we consider the effect of both friction c and the frequency of

instabilities, controlled by rj, on our results by computing the Kullback-Leibler (KL)

divergence

P(Pex, P) =

J

Pex(X) In PexW dx,

,P(x)

-00

(4.46)

which measures the relative information lost by using our approximate analytical pdf

P instead of the "true" or exact probability distribution Pex of the system from Monte

Carlo simulations.

34

-- Monte Carlo

-Analytic

-- Monte Carlo

10

-

Analytic

10

10

10 2

10 -10

100

110

100-4

10

-10

-5

-20

10

5

0

0

-10

10

20

X

X

Figure 4-9: Analytic pdfs (4.41), (4.45) compared with results from Monte Carlo

simulations for position (left) and velocity (right), for parameters: k = 2.6, m = 5.0,

c = 0.69, ox = 0.75.

For a more physical interpretation of the effect of the friction parameter, we instead

consider the typical number of oscillations the system undergoes during the decay

phase of an instability, i.e., the number of oscillations before the system returns back to

the stable regime. To determine the value of damping in terms of the average number

of oscillations N during the decay phase, consider that in Section 4.3 we derived the

approximation (4.16): Tims = (1 + 2A,<o/c)T,<o. In other words we have that the

duration of the decay phase is given by Tdecay - (2AK<o/c)TK,<o. Thus, the average

length of the decay phase is Tdeay = (2,K<o/c)T (where T denotes the conditional

average Tco), and the corresponding value of damping that will give on average N

oscillations during the decay phase is therefore

W~dc

27r

-s

2An<oW

27r

WsA<oc

irN

where T is given in (3.5) and w, in (4.7).

In Figure 4-10, we compute the KL divergence for a range of k and N parameter

values. For the simulations we fix m = 5.0, store values after 40 computational steps,

and use 4000 realizations for k < 2.0 and 2000 realizations, otherwise. In addition, we

compute the divergence for every half oscillation number from N = 0.5 to N = 3.0

and every k value from k = 1.4 to k = 3.6, in increments of 0.2, and interpolate values

in between. Overall, we have good agreement for a wide range of parameters, and even

when the analytical results do not capture the exact probability values accurately, we

35

have qualitative agreement with the overall shape of the pdf. The analytical results

deviate when we are in regimes with very frequent instabilities and instabilities of

long duration, i.e., small friction values or large N values. This is expected; in such

regimes the instabilities are no longer statistically independent, which we assume in

Al. Furthermore, an average of N = 1 oscillation during the decay phase shows good

agreement with Monte Carlo results for a large range values of the parameter 'q.

We also observe that deviations of the analytical approximation from the Monte

Carlo simulation become more prominent as k decreases. Note that for small k sampling

the tails is very hard since the critical events occur very infrequently in this case. To

understand the deviation of the analytical solution we recall that for this parametric

regime the unstable region is characterized by rare events which are shorter and weaker

and therefore harder to distinguish from the regular events. This explains the good

analytical approximation properties as k increases (but not too large), where we have

clear separation of the system behavior between the stable and the unstable regimes.

Finally, we emphasize that the KL divergence may be (relatively) large despite the

analytic pdf capturing the trend in the tails accurately; this is due to the fact that tail

events are associated with extremely small probability values, which the KL divergence

does not emphasize over the stable regime, where the probabilities are large and thus

any deviations (e.g., due to a cusp) can heavily impact divergence values.

36

KL divergence

log 10

KL divergence

- position

log10

- velocity

-1.8

-1.5

-1.9

2.5P