BE 225 – COURSE ASSESSMENT REPORT - 2015

advertisement

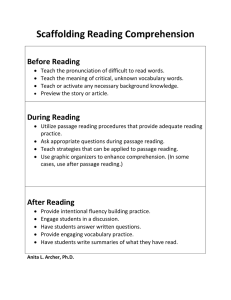

BE 225 – COURSE ASSESSMENT REPORT - 2015 Date: January 30, 2015 Department: Academic Literacy Course: BE225 Basic Reading Skills for ESL Students Curriculum or Curricula: LA PART I. STUDENT LEARNING OBJECTIVES For Part I, attach the summary report (Tables 1-4) from the QCC Course Objectives Form. (See Table #5 for Student Learning Objectives for Actual Assessment Assignment) TABLE 1. EDUCATIONAL CONTEXT BE 225 for ESL Students First course of a two-semester sequence (with BE-226) for students who speak English as a second language and who are in need of intensive instruction in fundamental reading and communication skills. Emphasis is placed on development of word recognition skills, knowledge of English idioms, listening skills, and literal comprehension. These skills include phonics and pronunciation, word structure analysis, dictionary use, multiple meanings of words, language patterns in reading, following directions, and basic notetaking skills from oral presentations. 1(26) TABLE 2. Curricular Objectives Note: Include in this table curriculum-specific objectives that meet Educational Goals 1 and 2: 1) Distinguish between details and generalities in texts. 2) Paraphrase the author’s main ideas. 3) Summarize passages by paraphrasing main ideas and adding a few sentences of supporting details (made up of paraphrases and/or quotes). 4) Distinguish between facts and opinions in texts. 5) Annotate texts using multiple techniques (e.g.. highlighting, marginalia, etc). 6) Distinguish between an inference and a stated claim. 7) Identify the author’s tone. 8) Identify and comprehend the idea of transition words. 9) Demonstrate effective group work skills through team project work and class reading groups. 10) Use context clues, dictionaries and root/prefix/suffix knowledge to understand unfamiliar words. 11) Use test-taking strategies to better manage time and self-access answers. 2(26) TABLE 3. General Education Objectives, based on draft Distributed at the January 2010 Praxis Workshops To achieve these goals, students graduating with an associate degree will: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. Communicate effectively through reading, writing, listening and speaking. Use analytical reasoning to identify issues or problems and evaluate evidence in order to make informed decisions. Reason quantitatively and mathematically as required in their field of interest and in everyday life. Use information management and technology skills effectively for academic research and lifelong learning. Integrate knowledge and skills in their program of study. Differentiate and make informed decisions about issues based on multiple value systems. Work collaboratively in diverse groups directed at accomplishing learning objectives. Use historical or social sciences perspectives to examine formation of ideas, human behavior, social institutions, or social processes. Employ concepts and methods of the natural and physical sciences to make informed judgments. Apply aesthetic and intellectual criteria in the evaluation or creation of works in the humanities or the arts. Gen Ed objective’s ID number from list (1-10) General educational objectives addressed by this course: Select from preceding list. 1. Communicate effectively through reading, writing, listening and speaking. 2. Use analytical reasoning to identify issues or problems and evaluate evidence in order to make informed decisions. 3(26) TABLE 4: Course Objectives and student learning outcomes Course Objectives and Desired Outcomes Upon successful completion of the course, while using some college-level texts,: 1) Students will be able to distinguish between details and generalities in texts. 2) Students will be able to paraphrase the author’s main ideas. 3) Students will be able to summarize passages by paraphrasing main ideas and adding a few sentences of supporting details (made up of paraphrases and/or quotes). 4) Students will be able to distinguish between facts and opinions in texts. 5) Students will be able to annotate texts using multiple techniques (e.g.. highlighting, marginalia, etc). 6) Students will be able to distinguish between an inference and a stated claim. 7) Students will be able to identify the author’s tone. 8) Students will be able to identify, comprehend, and use the idea of transition words. 9) Students will be able to demonstrate effective group work skills through team project work and class reading groups. 10) Students will be able to use context clues, dictionaries and root/prefix/suffix knowledge to understand unfamiliar words. 11) Students will be able to use test-taking strategies to better manage time and self-access answers. PART ii. Assignment Design: Aligning outcomes, activities, and assessment tools For the assessment project, you will be designing one course assignment, which will address at least one general educational objective, one curricular objective (if applicable), and one or more of the course objectives. Please identify these in the following table: 4(26) TABLE 5: OBJECTIVES ADDRESSED IN ASSESSMENT ASSIGNMENT Course Objective(s) selected for assessment: (select from Table 4) 1) Students will be able to distinguish between details and generalities in texts. 2) Students will be able to paraphrase the author’s main ideas. 8) Students will be able to identify, comprehend, and appropriately use transition words. Curricular Objective(s) selected for assessment: (select from Table 2) 1) Students will be able to distinguish between details and generalities in texts. 2) Students will be able to paraphrase the author’s main ideas. 8) Students will be able to identify, comprehend, and appropriately use transition words. General Education Objective(s) addressed in this assessment: (select from Table 3) 1. Communicate effectively through reading, writing, listening and speaking. Reading: Students will read various passages and summarize them. Writing: Students will write summaries. Listening and speaking: Students will discuss key components of main ideas in passages and summary writing in pairs, groups and as a class. 2. Students will use analytical reasoning to identify issues or problems and evaluate evidence in order to make informed decisions. Students will make informed decisions about which ideas are most important to include in their summaries. Students will learn to use analytical reasoning to determine what constitutes a major detail, which is included in their summaries vs. minor and more insignificant details that are omitted. Students who can achieve this objective will have a better opportunity to produce a successful and passing summary. Student Learning Outcomes: 1. Students will differentiate between major and minor details in reading passages. 2. Students will organize their ideas using appropriate transitional devices. 3. Students will write effective summaries on various reading passages. 5(26) In the first row of Table 6 that follows, describe the assignment that has been selected/designed for this project. In writing the description, keep in mind the course objective(s), curricular objective(s) and the general education objective(s) identified above, The assignment should be conceived as an instructional unit to be completed in one class session (such as a lab) or over several class sessions. Since any one assignment is actually a complex activity, it is likely to require that students demonstrate several types of knowledge and/or thinking processes. Also in Table 6, please a) identify the three to four most important student learning outcomes (1-4) you expect from this assignment b) describe the types of activities (a – d) students will be involved with for the assignment, and c) list the type(s) of assessment tool(s) (A-D) you plan to use to evaluate each of the student outcomes. (Classroom assessment tools may include paper and pencil tests, performance assessments, oral questions, portfolios, and other options.) Note: Copies of the actual assignments (written as they will be presented to the students) should be gathered in an Assessment Portfolio for this course. TABLE 6: Assignment, Outcomes, Activities, and Assessment Tools Briefly describe the assignment that will be assessed: Students will be taught to read a short passage and summarize it effectively. Desired student learning outcomes for the assignment (Students will…) Briefly describe the range of activities student will engage in for this assignment. What assessment tools will be used to measure how well students have met each learning outcome? (Note: a single assessment tool may be used to measure multiple learning outcomes; some learning outcomes may be measured using multiple assessment tools.) Baseline Assessment 1. Instrument Used: A Summary Scoring Rubric derived from the (MTEL) Communication and Literacy Skills Test (01) – List in parentheses the Curricular Objective(s) and/or General Education Objective(s) (1-10) associated with these desired learning outcomes for the assignment. 1) Students will distinguish between details and generalities in texts. (Curricular Objective #1) 2) Students will paraphrase the author’s main ideas. (Curricular Objective #2) 3) Students will summarize reading passages by identifying main ideas, organizing these ideas effectively, using appropriate transitional devices, and producing their summaries by using their own words.(Curricular Objectives #1,#2, and #8) In early October 2014, to form baseline data the instructors were asked to assess their students’ summarizing skills. Students were given a reading entitled, “Facebook Moms”(See Attachment One.) to read and summarize. The MTEL Rubric was used to evaluate their performance. (See Attachment Six.) Preparation for Mid-term Assessment: 6(26) The baseline, mid-term, and final summary results were assessed by using the MTEL rubric. (See Attachment Six.) Improvements between assessments were evaluated across sections and assessments to determine the improvement in students’ ability to write cohesive, accurate, and well-written General Education Objective #1 Students will communicate effectively through reading, writing, listening and speaking. Desired Learning Outcome: 1. Students will read articles and write well-organized, accurate, and effective summaries of reading passages. General Education Objective #2 Students will use analytical reasoning to identify issues or problems and evaluate evidence in order to make informed decisions. Desired Learning Outcome: 1. Students will be able to differentiate between major and minor details. Students will incorporate only the most important details into their summaries. In mid-November, instructors were given a specific lesson on summary writing to assist their students in learning this skill (See Addendum for specific details of the lesson that the teachers followed). Day of the Lesson: After teachers taught their students how to write a summary, which took approximately forty minutes, they gave students the passage on American Teen Health to read (See Attachment Two). This took approximately twenty-minutes. Once the students had finished reading it, they worked in pairs to write a summary of it. This task took approximately twenty to twenty-five minutes. Once the students had finished reading it, they worked in pairs to write a summary of it. This task took approximately twenty to twenty-five minutes. Once the students finished writing their summaries, the teachers noted the keys ideas of the passage on the board and asked students to verify whether or not they included these ideas. If they hadn’t, they were instructed to jot down notes below their summaries and, revise their summaries at home. Finally, the teacher gave students the second article, entitled,“ How Bullying’s Effects Reach Beyond Childhood by Alexandra Sifferlin (See Attachment Three) and asked them to summarize it for homework. During the following class, the teachers collected the homework summaries and revised in-class summaries. At 7(26) summaries. the beginning of class, teachers discussed the key points of the homework reading/summary. This took approximately fifteen minutes to twenty minutes. Mid-term Assessment: Several classes later, the students participated in the Department’s Mid-term Assessment of summary skill writing, which was measured with the MTEL (See Attachment Six). It should be noted that it is a departmental practice for all reading students to participate in this midterm summary assessment. This task required an entire class period. The mid-term reading “Conflicting Parenting Styles” by Nancy Rocks (See Attachment Four). Once the students finished writing their summaries, teachers placed them in the Dr. Julia Carroll’s (Chairperson of the Department’s Assessment Committee) mailbox labeled with the teacher’s name and class sections on them. The Assessment Committee then evaluated the summaries according to the MTEL rubric and recorded the scores on a separate file. Finally, the summaries were returned to the teachers. Preparation for the Final Assessment: At the end of the semester, the students participated in the Department Final Summary Assessment. Like the Mid-term, this assessment was a Department-wide Assessment, which all reading students were obligated to take. Prior to this assessment, teachers repeated the 8(26) summary lesson with their own readings passages. By revisiting this lesson, the teachers employed a spiral pedagogical approach whereby the same or very similar lesson was repeated on several occasions to reinforce learning. Day of the Actual Final Assessment The teachers administered the Final Exam, which included a summary. The passage that the students read and summarized was entitled “ I Think, Therefore I.M. by Jennifer Lee (see Attachment 5). The students were given the entire class period to complete the exam. Once again, teachers placed the materials in Dr. Carroll’s mailbox and the Assessment Committee evaluated them and recorded the scores on a separate roster, which was held on file. 9(26) Part iii. Assessment Standards (Rubrics) Before the assignment is given, prepare a description of the standards by which students’ performance will be measured. This could be a checklist, a descriptive holistic scale, or another form. The rubric (or a version of it) may be given to the students with the assignment so they will know what the instructor’s expectations are for this assignment. Please note that while individual student performance is being measured, the assessment project is collecting performance data ONLY for the student groups as a whole. Table 7: Assessment Standards (Rubrics) Describe the standards or rubrics for measuring student achievement of each outcome in the assignment: This assessment used the (MTEL) Communication and Literacy Skills Test (01) rubric to evaluate the summary skills of three sections of BE225 students on three separate occasions during the semester. (See Attachment Six.) The first summary served as a baseline assessment to ascertain how well students performed before receiving instruction. The next assessment was performed at the midterm after the students had experienced a specific summary lesson and practice activities. Finally, the last summary assessment was utilized at the end of the semester to measure the improvement across all three assessments. Instrument Used: A Summary Scoring Rubric derived from the (MTEL) Communication and Literacy Skills Test (01) – Background: The MTEL Summary Scoring Rubric was developed by Department of Education of Massachusetts and Pearson Education. It is a combined reading and writing test that incorporates the comprehension and analysis of readings as well as outlining and summarizing. It was first copyrighted in 2008 through Pearson Education. The Department of Academic Literacy at QCC utilizes this rubric to assess summary writing at midterms and finals across all reading courses. In addition, many writing instructors use it as well as a tool to assist their students with summary writing as part of their CATW assessment preparation. Since this rubric has been successfully used as the official rubric to assess summary writing throughout the Department, the members of the Assessment Committee concluded that it was an appropriate evaluation tool for the task of summary writing. This rubric consists of a four-point scale. The score of one represents the lowest score and is not passing. Two is approaching a passing level. Three is passing, and four is higher than passing. Some of the most important criteria that these scores are based on include: the extent to which the student understood the main idea of the article, how well the student organized his or her own ideas, the degree to which the student used his or her own words, and how clearly the summary was written. This rubric was provided to the BE225 instructors before they taught their lessons. Before their students participated in the assessments, the instructors discussed the criteria of the rubric so that the students would clearly understand how they were to be evaluated. How the MTEL Rubric Measured Curricular and General Educational Objectives for this Assessment: This rubric measured both Curricular Outcomes and General Education Outcomes. Curricular Objectives: 1) Students will distinguish between details and generalities in texts. (Curricular Objective #1) This curricular objective is included the in the MTEL because it examines how well students are able to locate an article’s most important ideas. 2) Students will paraphrase the author’s main ideas. (Curricular Objective #2) This curricular objective is included in the MTEL because it is critical that students learn how to identify the author’s overall intentions in a variety of genres. 10(26) 3) Students will summarize reading passages by identifying main ideas, organizing these ideas effectively, using appropriate transitional devices, and producing their summaries by using their own words. (Curricular Objectives #1, #2, and #8). All of these components above are included in the MTEL rubric. General Educational Objectives: 1. Communicate effectively through reading, writing, listening and speaking. (General Education Objective #1). The rubric measured how well the students read and understood reading passages as well as their ability to write an effective summary. 2. Use analytical reasoning to identify issue or problems and evaluate evidence in order to make informed decisions (General Education Objective #2). Part iv. Assessment results TABLE 8: Summary of Assessment Results Use the following table to report the student results on the assessment. If you prefer, you may report outcomes using the rubric(s), or other graphical representation. Include a comparison of the outcomes you expected (from Table 7, Column 3) with the actual results. NOTE: A number of the pilot assessments did not include expected success rates so there is no comparison of expected and actual outcomes in some of the examples below. However, projecting outcomes is an important part of the assessment process; comparison between expected and actual outcomes helps set benchmarks for student performance. TABLE 8: Summary of Assessment Results (Part of TABLE 9’s focus is subsumed in this section.) The committee started with the assumption that scores would increase as a result of (a) the lesson, and (b) multiple exposures to the new skill in a variety of situations (solo, group, examinations, and class-wide experiences). However, no specific expectations about the degree of improvement were hypothesized. Thus, the generally positive results seem to indicate a highly successful unit. Student achievement: Describe the group achievement of each desired outcome and the knowledge and cognitive processes demonstrated: The lesson had one desired outcome: to improve students’ ability to write effective summaries. The following analyses and discussions examine student improvements from the baseline assessment to the final assessment and from the midterm and to the final (See Table 1) and (See Table 2). Table 1 Comparison of Baseline, Midterm and Final Summary Assignment Baseline Midterm Final n Mean SD Improvement in Points 67 72 67 1.81 2.06 2.43 .500 .554 .529 .25 .37 .62 Total Improvement 11(26) Table 2 Comparison of Baseline, Midterm and Final Summary by Class Class 1 2 3 Assignment n Mean SD Improvement Baseline Midterm Final Total Improvement 22 23 22 1.77 1.91 2.36 .429 .288 .492 .14 .45 Baseline Midterm Final Total Improvement 21 24 21 Baseline Midterm Final Total Improvement 24 25 24 .59 2.00 2.42 2.52 .548 .717 .602 .42 .10 .52 1.67 1.84 2.42 .482 .374 .504 .17 .58 .75 Discussion of Individual Classes (Table 2) Although all three sections of BE225 improved over the course of the semester, there was variation among the classes. For example, Class #2 outperformed the other two sections in its overall improvement between the baseline and the midterm. For example, Class #2 achieved a mean score of a 2.0 on the original baseline assessment and was able to raise this score to 2.42. This was a .42 point improvement. In contrast, Class #1 and Class #3 had a far more modest improvement between these two assessments. Class #1 began by scoring a 1.77 mean score on the baseline assessment and was only increased to 1.91, which is only a slight improvement, a .14 point improvement. Likewise, Class #3 averaged a mean score of 1.67 on the baseline assessment and only increased its mean score of 1.84 , which is only a .17 point increase. However, ironically these other sections caught up by the end of the semester by demonstrating a more robust improvement between the midterm and the final assessment. Class #1 averaged a mean score of 1.91 on the midterm but by the final assessment managed to raise their mean score to a 2.36, which a .45 point improvement. Likewise, Class #3 also showed significant improvement raising its average mean score of 1.84, which was achieved on the midterm assessment to 2.42 on the final assessment, which is a .58 point improvement. Class #2, however, which had the highest mean score out of all of the three sections on the midterm assessment as well as demonstrating the most improvement between the baseline and the midterm, showed only slight improvement of .10 between the midterm and the final, a mean score of 2.52. One possible explanation for these differences might be that the students in Class 2 were perhaps a bit stronger from the beginning of the semester and were able to maintain that level until the very end of the semester, whereas the students in Class 1 and Class 3 needed more time to improve their scores. Overall, the students in all three sections did make gains from the beginning of the semester to the end of the semester even though the summary skills still need to improve. 12(26) Table 3 t Test of Dependent Means t df Significance MD Baseline 29.585 66 .000* 1.806 Midterm 31.493 71 .000* 2.056 Final 37.666 66 .000* 2.433 * p = .001 Discussion of Tables 1 and 3: A t-test of Dependent means revealed a significant difference (p = .000) between the initial baseline summary test and the midterm, and between the midterm and the final (p = .000). (See Table 1 for mean difference of the subjects.) When the baseline analysis was conducted, the mean summary score was 1.806. However, by the midterm, the mean score had increased to 2.056, and by the final it had risen to 2.43. This analysis indicates that these students benefited from a spiral pedagogy, whereby the students were taught to summarize early in the semester and summarizing was revisited and reviewed throughout the term to reinforce the skills required. However, it should be noted that in order to exit remedial reading classes, students need to achieve a minimum score of three (3) on their final summary. Thus, although these students improved significantly, they still need to enhance their ability to summarize so that they will be able read and comprehend entry-level college textbooks in gateway courses such as English composition, psychology, sociology, criminology, etc. 13(26) TABLE 9. Resulting Action Plan In the table below, or in a separate attachment, interpret and evaluate the assessment results, and describe the actions to be taken as a result of the assessment. In the evaluation of achievement, take into account student success in demonstrating the types of knowledge and the cognitive processes identified in the Course Objectives. A. Analysis and interpretation of assessment results: See section 8 above. B. Evaluation of the assessment process: What do the results suggest about how well the assignment and the assessment process worked both to help students learn and to show what they have learned? The results of this analysis suggest that the students entered this class with weak summarizing skills averaging only 1.81 on the baseline assessment that was measured by the MTEL Summary Rubric. However, these students evidence a moderate improvement after instruction on the midterm by scoring 2.06, which demonstrates an increase of .25 points or 14 % between the two assessments. In addition, they further improved their scores by averaging 2.43 on the final assessment, which is an increase of .37 points or 18 % between the midterm and the final. Overall, the students improved their scores by .62 points or 34 % between the final and the baseline at the beginning of the semester. These results suggest that the assignment, which was designed by a team of experts who have taught ESL reading and writing for many years, worked well in that it used a repeated or spiral approach to teaching the same concept. These results also infer that these students could have increased their scores more between the two assessments if they had benefited from more time on task, exposure to the target language, and additional repeated lessons focused on summary writing. Results on the MTEL Summary Scoring Rubric evidenced a statistical improvement in the participants’ ability to summarize as a result of repeated lessons, practice, and exams (See Table 3). These results suggest that if these students were taught with a traditional method, which included a) one lesson of instruction, b) in class group practice, c) in class individual practice, d) homework practice, and e) an exam, they would not have been able to improve their mastery of this skill. However, when the teachers used a spiral pedagogy and revisited the instruction and practice of this topic, the students increased their scores significantly. Therefore, these results suggest that most of these BE225 students will continue to need exposure to summarizing lessons, practice and exams as they advance to BE226. C. Resulting action plan: Based on A and B, what changes, if any, do you anticipate making? Modest gains were achieved using the MTEL, to measure summary skills. It measured how well a student comprehended a passage and was able to summarize it in his or her own words effectively. The results from this assessment revealed that the students’ ability to summarize improved over time significantly. This assessment insinuates that explicit repeated teaching of a) differentiating the main idea of a passage from extraneous minor details, b) paraphrasing, c) using transitions, and d) organizing a well-organized cohesive summary, leads to enhanced ability to write effective summaries, and since summary writing is an essential skill that all of our reading students will need to pass their future classes as well as the Department Exit Summary test, which employs the MTEL, BE225 faculty will be encouraged to use this spiral teaching, writing, and testing method as they fine tune their courses. In recent years, our Department has endeavored improve all areas of instruction and assessment, by incorporating High Impact Practices in all of our classes. As a result, we have created more dynamic and creative curriculum, unrelated to this assessment . However, since our low-level ESL reading students arrive with weak linguistic and academic skills, they still require much more exposure to the target language. Moreover, since our Department only provides four ESL writing 14(26) instructional hours per week in this course, compared to similar departments throughout CUNY that average 6-8 hours for the same type of course and level, they are at a disadvantage. Therefore, instructors need to compensate for the lost time by including more intensive instruction. This can consist of additional repeated lessons, challenging academic material, and consistent review of the skills necessary to write an effective summary. It is suggested that each time instructors in the lowerlevel ESL classes introduce a new reading or writing techniques, they be prepared to revisit these new skills with supplemental lessons, exercises, homework and exams throughout the semester to ensure that the students can utilize the new skill effectively since “one shot” lessons are not sufficient because our ESL learners arrive with both linguistic and academic deficiencies. To enhance this lesson further, instructors can be encouraged to develop model summaries that directly correspond to the criteria of the rubric being utilized. For instance, students can be provided with sample summaries that have received the score of a 1, 2, 3, or 4 on the rubric. The samples can be distributed to the students without their corresponding scores and then the students can work in groups to assess each summary. The classroom instructor can then lead the students through a discussion/analysis of the scores that each summary should have received and the rationale behind each decision so that the students view summarizing from the teacher’s perspective. After this review, the students should score each other’s summaries to enhance their understanding of this skill by analyzing and discussing their summaries along with the rubric. Teaching students to examine their work from the evaluator’s point of view will enhance the students’ ability to think more critically. Likewise, all BE225 instructors should participate in norming sessions during which they utilize these model summaries along with their corresponding rubrics to ensure consistency and accuracy in their grading. These sessions will also permit teachers to glean ideas from one another to enhance their summary teaching even more. This will be especially helpful in that it will increase the likelihood of fewer discrepancies among BE225 sections because the instructors will be exposed to increased support from their peers. If, by the end of the semester, students in BE225 remain at a low level, then it is important that instructors not pass them into BE226 because they are unprepared to meet the demands of the criteria of that higher level. This will prevent these students from becoming multiple repeaters, and thereby reduce the multiple-repeaters issue in our Department. 15(26) Addendum: Lesson Plans and Teacher Instructions The following documents were provided to each teacher so that he/she would teach the same lesson in each class. Instructor’s Packet: Lesson plan, assessment* and reading passages* Used in the Fall 2014 Assessment of BE2011 Session #1 Overview of the Lesson The focus of this lesson is finding the key ideas in a reading passage and writing a summary using those key ideas. The focus of the lesson will be the following: Review a simplified 4-point rubric with particular focus on a score of “3” as a passing summary. Read the passage Identify the overall topic, main idea, and key ideas within the passage. Draft a summary. Include transition words that indicate an additional idea. Edit for simple sentence structure and main idea/key ideas (time permitting) The Summary Rubric The attached MTEL Summary Scoring Rubric for teacher reference and the simplified version of that rubric is for class review. To help students understand the important parts of a summary, you can focus on “3” as the target for summary writing because it is considered to be a passing score. The Reading Passage #1 The attached reading passage (The Teens Are Alright (Healthwise, at Least) will be used to demonstrate how to find the topic, main idea, and key ideas. We suggest that you and the students work together on the initial part of this task (finding the topic and main idea) and allow them to work in pairs for the second part of the task (finding key ideas). Addendum continued: These documents were included in the instructor’s packet for the fall 2014 Assessment of BE 225. They include: a) the lesson plan, b) reading passages and c.) the rubric The reading passages and MTEL Summary Scoring Rubric referred to in the lesson are attached to the end of this section. 1 The rubrics and reading passages referred to in the lesson are at the end of this section. 16(26) Overview of the Lesson for Session #1 The focus of this lesson is finding the key ideas in a reading passage and writing a summary about those key ideas. The focus of the lesson will be the following: o Review the MTEL Summary Scoring Rubric with particular focus on a score of “3” as a passing summary. Read the passage Identify the overall topic, main idea, and key ideas within the passage. Draft a summary. Include transition words that indicate an additional idea. Edit for simple sentence structure and main idea/key ideas (time permitting) The Summary Rubric The Department of Academic Literacy at QCC utilizes the MTEL Summary Scoring Rubric to assess summary writing at midterms and finals across all reading courses. This rubric consists of a four-point scale. The score of one represents the lowest score and is not passing. Two is approaching a passing level. Three is passing, and four is higher than passing. Some of the most important criteria that these scores are based on include: the extent to which the student understood the main idea of the article, how well the student organized his or her own ideas, the degree to which the student used his or her own words, and how clearly the summary was written. To help students understand the important parts of a summary, you can focus on “3” on the four-point scale as the target for summary writing because it is considered to be a passing score. We suggest that you and the students use the attached rubric to carefully examine differences in scores on the scale; such analysis can help students to understand the differences between a failing and passing summary score. One approach is to focus on the description of how well main ideas and significant details are conveyed in the summary at the “3” level vs. the “2” or “1”. For example, going from “3” to “1” on the scale reveals different levels of performance 17(26) in summary writing. You can ask the students to examine the first bullet point in score level and underline the words that show those differences and consider the meaning with regard to scoring: 3 The response conveys most of the main ideas and significant details of the original passage, and is generally accurate and clear. 2 The response conveys only some of the main ideas and significant details of the original passage. 1 The response failsto convey the main ideas and details of the original passage. Once students analyze those differences in scoring, you could ask them to consider the “4” vs. “3” level by eliciting definitions for “accurately” and “clearly” in the context of good summary writing. 4 The response accurately and clearly conveysall of the main ideas and significant details of the original passage. If time permits further analysis, you and the students can compare other bullet points in scoring levels (paraphrasing, organization, and clarity). The Reading Passage #1 The attached reading passage (Why Obesity Among 5 Year Olds Is So Dangerous) will be used to demonstrate how to find the topic, main idea, and key ideas. We suggest that you and the students work together on the initial part of this task (finding the topic and main idea) and allow them to work in pairs for the second part of the task (finding key ideas). Determining the Topic and Main Idea of Reading Passage #1 1. The topic of a reading passage is usually a few words that express the most general point that is discussed in the passage. Elicit student responses about the topic of the passage. 2. Next, the main idea of the entire passage usually contains the topic and the author’s opinion or the point being made. Elicit student responses about the main idea of the passage. Determining the Key Ideas in the Passage 18(26) After you and the students have reviewed the topic and main idea of the passage, you can ask pairs to find the key ideas in the passage. It is sometimes challenging for developmental reading students to understand the difference between general and specific ideas. Therefore, we recommend that you work on this concept with the students before they participate in pair work. For example, you can write down several examples of general vs. specific ideas on the board to model this concept and/or elicit examples from the students such as fruit (general) and kinds of fruit (specific). When you think students are ready to work on their own, ask them to highlight or underline only the key ideas in this passage. When the pairs have finished, review key ideas with the whole class. Paraphrasing for the summary After the topic, main idea, and key ideas have been identified, pairs can work on drafting the summary. Drafting a passing summary (“3” score) requires paraphrasing, and we suggest you elicit students’ knowledge of this skill. Depending on student responses about paraphrasing, you may want to say that writing a good summary means that students should change some of verbs, adjectives, and nouns with synonyms (or words with similar meanings), and/or sentence structure. Below is one example of changing verbs, adjectives and/or nouns: Example #1: Original sentence: A news report that studied kids throughout childhood found that those who are obese at five years old are more likely to be heavy later in life. Revised sentence: A recent longitudinal study of children revealed that overweight five-year-olds were more likely to be overweight adults. Below is an example of changing sentence structure from compound to complex: Example #2: Original sentence: The study highlights the dynamic between early weight gain and obesity, and the researchers say future work should focus on understanding what contributes to a child becoming overweight so early in life. 19(26) Revised sentence: Since the research shows how gaining weight during childhood is linked to obesity, researchers believe that other studies should explore contributing factors that lead to early childhood obesity. Writing the Summary Ask students to draft a summary by stating the following: The title of the passage The author of the passage The topic of the passage The main idea The key ideas Adding Transition Words The next part of drafting a summary is writing with coherence. Again, coherence may be a complex or unknown term for developmental reading students, so we recommend discussing this aspect as making connections with words that add ideas. Elicit transition words that help students to add ideas into their writing. Ask students to look at their summary closely to see where they might be able to add transition words. The Homework Assignment For homework, ask students to read the attached passage #2 (Reading Passage Two: How Bullying’s Effects Reach Beyond Childhood by Alexandra Sifferlin and draft a summary on their own. Remind them that the summary should include the title, author’s name, topic, main idea, and key ideas. Session #2 Review the homework summary as a whole class for content and coherence. After homework review, assign the individual in-class assessment activity. 20(26) Attachment One Baseline Reading Facebook Moms By Tracey Harrington McCoy Kimberly Gervaise, a stay-at-home mother of three in Little Silver, N.J., joined Facebook five years ago and only posts every couple of months, mostly sharing photos from special events, like birthdays. She has 393 friends, and wishes some of them would tuck it in a bit. “I get a little upset about people who feel the need to post a picture of a straight-A report card – and there are many,” she says. “I am sure that most of the time, they are just proud, but I find it annoying.” Gervaise says more and more mothers are using Facebook as a way to brag about their lives, their kids, their parenting techniques. And that’s making it harder and harder for moms like her to log on without feeling slapped in the face. Bragging about your kids is nothing new, but before Facebook, the Compare & Contrast game was mostly played at the playground or the preschool parking lot. Moms would stand around quietly assessing kids to see who was hitting major moments in their lives faster or slower than their own children. Facebook moms are constantly informed of updates about their friends’ kids and their accomplishments. Daily, hourly even. According to Edison Research’s Moms and Media 2013 report, 57% of moms on Facebook are over 35 – these women are the first generation to have raised their children entirely in the Facebook era. Mothers are heavy Facebook users. Edison’s 2013 research reveals that 7 out of 10 moms have a profile, and there are more than 1,000 mommy groups, public and private. These groups range in size from hundreds of members to tens of thousands, and they are discussing everything from potty training to gaming that private-school admissions test. Of all the different groups that use Facebook, moms check in the most (an average of 5.1 times a day, according to Edison), and they keep coming back, even if they are being hit with difficult to notice – and sometimes not so difficult – "My kid’s smarter/healthier/happier than yours” criticisms. For the mom who barely gets her kids’ shoes on before rushing them off to school, posts that show the perfect family can create guilt or even self-hatred. “Who has time to get the paint and glitter out? Who has time to clean up the giant mess?” says Meredith DePersia, a working mother of two in San Francisco. “ This situation is turning many women off. For instance, an online media professional and mom of one from Falls Church, Va., is so tired of playing the game that she’s taken her ball and gone home. “I kind of avoid Facebook entirely,” she says, “because I'm sick of everyone's presentation of perfection.” Adapted from Newsweek magazine, October 4, 2013 21(26) Attachment Two Reading Used as In Class Writing Assignment Passage One: Why Obesity Among 5 Year Olds Is So Dangerous By Alexandra Sifferlin A new report that studied kids throughout childhood found that those who are obese at five years old are more likely to be heavy later in life. While other studies have hinted at that trend, those have generally involved what’s known as prevalence of the condition — or the proportion of a population, at a given time, that is considered obese. Such information doesn’t suggest the risk of developing obesity, which is revealed by studying a population over specific periods of time. So in the latest study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, scientists tracked a group of 7738 children, some of whom were overweight or obese, and some who were normal weight, from 1998 (when they were in kindergarten) to 2007 (when they were in ninth grade). They found that the 14.9% of five-yearolds who were overweight at kindergarten were four times more likely to become obese nearly a decade later than five-year-olds of a healthy weight. During the study, the researchers measured the children’s height and weight seven times, which allowed them to record the incidence of obesity almost yearly. Overall, since most of the children (6807) were normal weight at the start of the study, the children’s risk of becoming obese decreased by 5.4% during the kindergarten year and by 1.7% between the fifth and eighth grades. But the five-year-olds who were overweight, defined as having a body mass index (BMI) within the 85th percentile for their age group were significantly more likely to become obese, which the scientists defined as a BMI within the 95th percentile of their age group as time went on. Among kids who became obese between the ages of five and 14, about half had been overweight in the past and 75% were in a high BMI percentile at the start of the study. Obesity is connected to a high risk of chronic conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, and stroke among adults, and young children who spend more years overweight or obese may be putting themselves at even higher risk of these diseases, the scientists say. The study highlights the dynamic between early weight gain and obesity, and the researchers say future work should focus on understanding what contributes to a child becoming overweight so early in life. The results suggest that education about weight gain and obesity prevention efforts may need to start earlier with families of young children, before youngsters become locked in a condition that’s difficult to change. 22(26) Attachment Three Reading Used as Homework Summary Assignment Reading Passage Two: How Bullying’s Effects Reach Beyond Childhood by Alexandra Sifferlin More research is documenting the lasting effect of bullying on its victims in nearly every part of their lives, from emotional wellbeing to career success. The latest analysis from researchers at the University of Padua in Padua, Italy, sadly confirms the obvious — that children who were bullied suffered from issues with low self confidence, poor grades, and physical health problems that had a direct influence on the state of their health as adults. The study, published in the journal Pediatrics, reviewed data from 30 studies that investigated the connection between being bullied and so-called psychosomatic problems that include headaches, backaches, abdominal pain, skin problems, sleeping problems, bed- wetting, or dizziness. The results showed that kids who were bullied were twice as likely to have psychosomatic symptoms compared to their non-bullied peers. The severity and influence of bullying is certainly increased by the variety of online avenues by which bullying can take place, which extends it beyond the school to students’ private lives, making it harder for kids to ignore, overcome and move on. Studies document higher rates of anxiety and panic attacks among victims of bullying, and these are causing mental health and behavior problems later in life. That could translate into unstable professional and personal lives as well; a recent study reported that bully victims are two times less likely to hold down a job and also have difficulty maintaining meaningful social relationships. The psychosomatic symptoms, however, may also represent an opportunity — sometimes the first and only one — for doctors or parents to recognize bullying and intervene. The researchers say, for example, that pediatricians can play a larger role in identifying bully victims during check-ups if such symptoms are persistent and long-lived. Discussing these warning signs with parents, as well as counseling them on how to handle bullying when it occurs can help to promote selfconfidence and in some cases ease the situation. “Pediatricians’ suggestions are likely to be particularly effective given the high confidence that parents usually put in these professionals, the authors write. Adapted from Time magazine, September 16, 2013. 23(26) Attachment Four Departmental Mid-Term Assessment Conflicting Parenting Styles By Nancy Rocks Imagine how you would feel if you had to live in two separate households every week. Now, imagine it from a child's perspective with different daily routines and different interpersonal relationships. Clearly, children of separated or divorced parents sometimes have to adjust to very different parenting styles and living arrangements: To understand how a child has to balance his changed environment, let's examine some of these contrasts to see how they affect behavior and development. Often, the most conflicting parenting style is illustrated in after-school and bedtime routines. In our home, my l l-year-old son, Andrew, has a bedtime of 8:OO on school nights. He generally does his homework at 6:30, showers at 8:15, and then gets ready for bed. He usually reads for l5 or 20 minutes before falling asleep. Conversely, on the days he is with his father, Andrew goes to his grandmother's after school and does his homework there. After his dad picks him up, they have dinner at approximately 7:30, and Andrew stays up until 10:00. He has a television in his room at his dad's, so instead of reading at bedtime, he most often plays video games. Another conflicting living arrangement is the introduction of new relationships. Just as children need time to adjust to their parents' separation, so, too, do they need to prepare for their parents' new partners. For example, I chose not to introduce anyone into my children's lives until I am divorced from their father. Instead, I am allowing them to become accustomed to the changes already taking place. In contrast, our children share their father's home with his new woman. That arrangement has provided them very little opportunity to adapt to the new intimacy through a steady, natural process. A very important transition for the child is in maintaining friendships at both homes. Here, Andrew has many friends on our block and has grown up with most of them. They play basketball at our house, baseball at Joey's, and jailbreak at Eric's. Andrew knows everyone's mom, and we parents are attuned to looking out for each other's children. On the other hand, Andrew has a new friendship with a boy who lives near his dad's apartment. Living in an apartment complex, there is less freedom and peace of mind to let the children play outside. Consequently, Andrew and his friend Steve are more likely to play indoor, with less chance for Andrew to experience the nurturing sense of community. A further disparity in recreational activities involves toy and gifts. Andrew earns an allowance from me by doing his weekly chores, and I deposit a portion of it into his savings account. He lets the balance accumulate for several weeks until he can't wait any longer to spend it. Since the first time I took him to Border's Bookstores, he enjoys going there to buy books. Of course, there are times when only a new toy will do, but, about half the time, I suggest we go the Borders's, and he carefully chooses the best books for his money. Conversely, on those occasions that his dad rewards Andrew for a great report card, for example, Andrew most often chooses to buy a toy or a video game. Because Andrew's dad does not read for leisure, Andrew follows tile pattern of that household. All these examples illustrate the difficult transitions children face in just one aspect of a divorce-that of two households. It is particularly difficult when the parents have such contrasting parenting styles. As a mother, I look for ways to ease their passage and soften the effect, but I oversee my own household, and only my own. Therefore, I believe it is critical to the emotional health of the children that parents find a way to cooperate and maintain open communication with each other. The wellbeing of the children is, and should always be, the first priority. 24(26) Attachment Five Final Department Summary Reading I Think, Therefore I.M. By: Jennifer Lee Each September Jacqueline Harding prepares a classroom presentation on the common writing mistakes she sees in her students' work. Ms. Harding, an eighth-grade English teacher at Viking Middle School in Chicago scribbles the words that have plagued generations of schoolchildren in her class: There. Their. They're. Your. You're. To. Too. Two. Its. It's. This September, she has added a new list: u, r, ur, b4, wuz, cuz, 2. As more and more teenagers socialize online, middle school and high school teachers like Ms. Harding are increasingly seeing a looser form of “Internet English” move from text messages and e-mail into students’ schoolwork. To their dismay, teachers say that papers are being written with shortened words, improper capitalization and punctuation, and characters like &, $ and @. Teachers have deducted points and drawn red circles, but the improper forms of English continue. "It stops being funny after you repeat yourself a couple of times," Ms. Harding said. But teenagers, whose social life can rely as much these days on text communication as the spoken word, say that they use shortened, instant messaging “language” without thinking about it. They write to one another in this way as much as they write in school -- or even more. As Trisha Fogarty, a sixth-grade teacher at Houlton Southside School in Houlton, Maine, puts it, today's students are "Generation Text." Almost 60 percent of the online population under age 17 uses instant messaging, according to Nielsen/NetRatings. In addition to cell phone text messaging, blogs and e-mail, it has become a popular means of flirting, setting up dates, asking for help with homework and keeping in contact with distant friends. The abbreviations and language which are used in texts and e-mail are a natural outgrowth of this rapid-fire style of communication. "To students it's not wrong," said Ms. Harding, who is 28. "It's acceptable because it's in their culture. It's hard enough to teach them the skill of formal writing. Now we've got to overcome this new instant-messaging language." Teenagers have long pushed the boundaries of spoken language, always introducing new words. Now teenagers are taking charge and pushing the boundaries of written language. For them, expressions like "oic" (oh I see), "nm" (not much), "jk" (just kidding) and "lol" (laughing out loud), "brb" (be right back), "ttyl" (talk to you later) are as standard as the conventional English they use in school. Some teachers find the new writing style alarming. "First of all, it's very rude, and it's very careless," said Lois Moran, a middle school English teacher at St. Nicholas School in Jersey City. "They should be careful to write properly and not to put these little codes in that they are in such a habit of writing to each other," said Ms. Moran, who has lectured her eighth-grade class on such mistakes. Others say that the instant-messaging style might simply be a short-term trend, something that students will grow out of. Or they see it as an opportunity to teach students about the evolution of language."I turn it into a very positive teachable moment for kids in the class," said Erika V. Karres, an assistant professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill who trains student teachers. She shows students how English has evolved since Shakespeare's time. "Imagine Shakespeare writing in quick texting instead of ‘Shakespeare writing,' " she said. "It makes teaching and learning so exciting." 25(26) Attachment Six SCORING RUBRICS FOR COMMUNICATION AND LITERACY SKILLS: WRITTEN SUMMARY EXERCISE (MTEL) Summary Scoring Rubric Score Point Description 4 The response accurately and clearly conveys all of the main ideas and significant details of the original passage. It does not introduce information, opinion, or analysis not found in the original. Relationships among ideas are preserved. The response is concise while providing enough statements of appropriate depth and specificity to convey the main ideas and significant details of the original passage. The response is written in the candidate's own words, clearly and coherently conveying main ideas and significant details. The response shows excellent control of grammar and conventions. Sentence structure, word choice, and usage are precise and effective. Mechanics (i.e., spelling, punctuation, and capitalization) conform to the standard conventions of written English. 3 The response conveys most of the main ideas and significant details of the original passage, and is generally accurate and clear. It introduces very little or no information, opinion, or analysis not found in the original. Relationships among ideas are generally maintained. The response may be too long or too short, but generally provides enough statements of appropriate depth and specificity to convey most of the main ideas and significant details of the original passage. The response is generally written in the candidate's own words, conveying main ideas and significant details in a generally clear and coherent manner. The response shows general control of grammar and conventions. Some minor errors in sentence structure, word choice, usage and mechanics (i.e., spelling, punctuation, and capitalization) may be present. 2 The response conveys only some of the main ideas and significant details of the original passage. Information, opinion, or analysis not found in the original passage may substitute for some of the original ideas. Relationships among ideas may be unclear. The response either includes or excludes too much of the content of the original passage. It is too long or too short. It may take the form of a list or an outline. The response may be written only partially in the candidate's own words while conveying main ideas and significant details. Language not from the passage may be unclear and/or disjointed. The response shows limited control of grammar and conventions. Errors in sentence structure, word choice, usage, and/or mechanics (i.e., spelling, punctuation, and capitalization) are distracting. 1 The response fails to convey the main ideas and details of the original passage. It may consist mostly of information, opinion, or analysis not found in the original. The response is not concise. It either includes or excludes almost all the content of the original passage. The response is written almost entirely of language from the original passage or is written in the candidate's own words and is confused and/or incoherent. The response fails to show control of grammar and conventions. Serious errors in sentence structure, word choice, usage, and/or mechanics (i.e., spelling, punctuation, and capitalization) impede communication. U The response is unrelated to the assigned topic, illegible, primarily in a language otherthan English, not of sufficient length to score, or merely a repetition of the assignment. B There is no response to the assignment. 26(26)