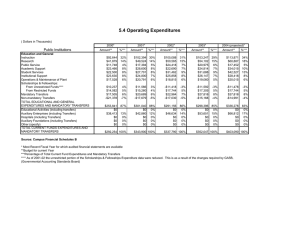

Cash Transfers Literature Review Policy Division 2011

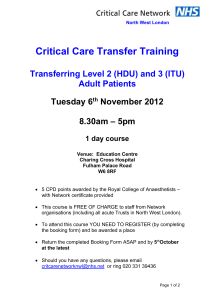

advertisement