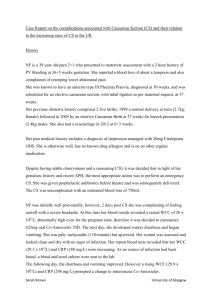

Call me 'at-risk': Maternal Health in ... Cesarean Technology

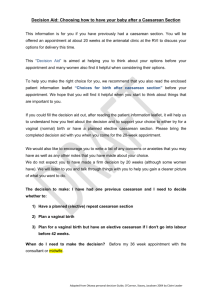

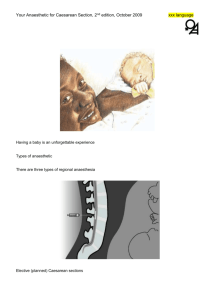

advertisement