Castan Centre for Human Rights Law Monash University Melbourne

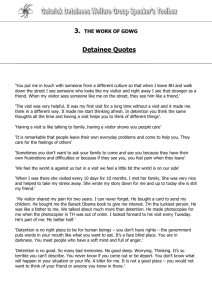

advertisement