IX. COMMUNICATION RESEARCH A. MULTIPATH TRANSMISSION

advertisement

IX.

A.

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH

MULTIPATH TRANSMISSION

Prof. L. B. Arguimbau

Dr. J. Granlund

Dr. C. A. Stutt

1.

Speech and Music.

E. M. Rizzoni

G. M. Rodgers

R. D. Stuart

Cross

H.

W.

E.

R.

Kinzinger

Manna

Paananen

Transatlantic Tests

The present series of tests has been completed and will be discussed in some detail

in the next Quarterly Progress Report.

J. Granlund, C. A. Stutt, L. B. Arguimbau

2.

Television

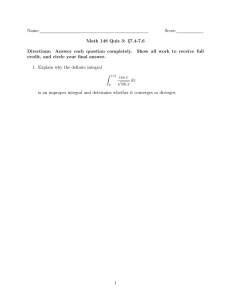

Tests are being made to check the typical requirements placed on a television system

by multipath conditions.

A single-line scanner is being constructed to display test pat-

terns from local television stations and provide a measure of the relative delays and

amplitudes of the various paths.

E.

3.

M.

Rizzoni

Simplified FM Receiver

The design of the i-f amplifier has been completed,

technique outlined in Technical Report No.

using the approximation

145 by J. G. Linvill.

Seven tuned circuits are

used as opposed to the typical six circuits used in home receivers.

This design has

met the requirements broadly outlined in the Quarterly Progress Report, October 15,

1951.

Limiters have been made, using gated-beam (6BN6) tubes; they have been compared

with the crystal diode limiters discussed in earlier Quarterly Progress Reports.

The

gated-beam type has been found to saturate more fully than the crystal type and to be

superior in most respects.

In particular,

it has been found workable in conjunction

with wide-band discrimination and preserves all the accompanying advantages of low

6AI

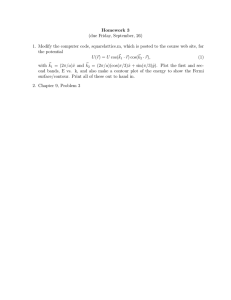

Fig. IX-1

A simplified version of the wide-band detector.

-49-

(IX.

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

capture ratios.

A slight modification of the wide-band detector discussed in Technical Report No. 42,

by J. Granlund produces the circuit shown in Fig. IX-1. Notice that the cathode supplies

the bias needed for the crystals.

R. A. Paananen

The design of a tuning head for a frequency modulation broadcast receiver has been

brought to the working-model point.

Using variable capacitor tuning, and a single stage

of tuned radiofrequency amplification,

all spurious responses are down at least

80 db (for interfering signals below 0. 4 volt) and the sensitivity is comparable to usual

commercially available receivers.

At a slight sacrifice in spurious response rejection,

sensitivities can be improved by increasing the couplings in the input tuned circuits.

Noise figures as low as 6 db have been measured, in the latter case.

H. H. Cross

The effect of discriminator bandwidth on adjacent and alternate channel interference

is under investigation.

W. C. Kinzinger

-50-

(IX.

B.

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

STATISTICAL THEORY OF COMMUNICATION

Prof. J. B. Wiesner

Prof. W. B. Davenport,

Prof. R. M. Fano

Prof. Y. W. Lee

Prof. J. F. Reintjes

Dr. P. Elias

1.

B.

R.

J.

M.

C.

L.

B.

Jr.

E. Green, Jr.

Howland

G. Kraft

A. Basore

S. Berg

J. Bussgang

Coufleau

A. Desoer

Dolansky

M. Eisenstadt

A. J. Lephakis

R. M. Lerner

M. J. Levin

Multichannel Analog Electronic Correlator

A suitable integrating circuit has been developed. The remainder of the design work

for the correlator has been completed. Testing of the equipment is proceeding.

Y. W. Lee, J. F. Reintjes, M. J. Levin

2.

Analog Electronic Correlator for Second-Order Correlation

The second-order autocorrelation function of a random or periodic function fl(t) is

defined as

111(

T1)) = lim

T--oo

1

f fl(t) fl(t

+ T1) fl(t + T2 ) dt.

-T

Equipment is not yet available for plotting this function.

111 ( 0 , T2)

=

f (t) f(t

lim

T-oo

=

However, if T 1

+ T)

0

(2)

dt.

For this special case the second-order autocorrelation function can be obtained by

crosscorrelating f (t) with fl(t). This has been done as shown in Fig. IX-2.

LADDER NETWORK

ELECTRONIC

ANALOG

CORRELATOR

QU

A CHANNEL

CIRCUIT

B CHANNEL

f(t)

Fig. IX-2

Fig. IX-3

Arrangement for obtaining second-order

autocorrelation functions.

Squaring circuit.

-51-

(IX.

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

The squaring circuit(J. S. Rochefort: "Design and Construction of a Germanium-Diode

Square-Law Device, " Master's Thesis in Electrical Engineering, M.I.T. 1951) makes

use of the nonlinear properties of 1N34 germanium diodes (see Fig. IX-3). A twoterminal ladder network composed of resistors and these diodes has been constructed.

This network has a variable driving-point impedance such that the current through it

is proportional to the square of the voltage across it.

The voltage across a small

resistor in series with the network is then proportional to the square of the input voltage.

The sign of the output should be positive whether the input is positive or negative for

proper square-law action.

circuit.

This characteristic is obtained by using a push-pull driver

Since the driver circuit works into a varying impedance it was designed to

have a very low output impedance for accurate operation.

Appreciation is expressed

to Mr. Rochefort for providing the necessary information for the design of this unit.

If the function fl(t) in Eq. 1 is periodic and has the spectrum Fl(n) with the fundamental angular frequency wl,

so that

oo00

f (t) =

F 1 (n) e

(3)

n= -c

it can be shown that the second-order autocorrelation function of fl(t) is

o00

111(T2)

0m

F 1 (m) Fl(n)

=21

F 1 (m+n)

e

j(m+n)wl(Tl + T )

2

m=-oo n=-oo

For the particular case where fl(t) is an odd-harmonic function,

111 (T 1 , T 2

) vanishes

for all values of T 1 and 7 2 since Fl(m+n) is zero.

Figure IX-4b shows the autocorrelation function of the half-wave rectified sinusoid

which is illustrated in Fig. IX-4a. Figure IX-4c shows the second-order autocorrelation function of this wave. For a wave of the form shown in Fig. IX-5a, the autocorrelation function and the second-order autocorrelation function are given in

Figs. IX-5b and IX-5c respectively.

Y. W. Lee, J. F. Reintjes, M. J. Levin

3.

a.

Information Theory

Transmission of information through channels in cascade

Further investigation of this problem has indicated that the operation of the intermediate receivers is the important factor in the performance of the over-all system.

For example, in the pulse code modulation system analyzed previously the receiver

requantizes the received pulses.

This requantization process eliminates the noise in

almost all instances although errors are introduced once in a while.

-52-

(A relatively

Fig. IX-4a

Fig. IX-Sa

Half -wave rectified

sinusoid.

Triangular wave with odd

harmonic function.

Fig. IX-4b

Fig. IX-Sb

Autocorrelation of waveform

in Fig. IX-4a.

Autocorrelation of waveform

in Fig. IX-Sa.

Fig. IX-4c

Fig. IX-Sc

Second-order autocorrelation of

waveform in Fig. IX -4a.

Second -order autocorrelation of

waveform in Fig. IX-Sa.

General data pertaining to curves: AT = 5 IJ.sec; number of samples = 8000; fundamental frequency of input wave = 3.5 kc/sec except for Fig. IX-4c where it is 2 kc/sec.

-53-

Fig. IX-6

Fig. IX-7

E as in Eve.

U as in Boot.

Fig. IX-8

Fig. IX-9

S as in Hiss.

F as in Gaff.

Fig. IX-lO

Fig. IX-II

Z as in Craze.

A as in Father.

-54-

(IX.

high S/N is assumed.)

COMMUNICATION

RESEARCH)

The introduction of definite errors can be shown to result in

additional loss of information; it appears that any attempt to eliminate a fraction of

the noise necessarily involves an additional loss of information.

On the other hand,

if some of the noise contained in the signal is eliminated, the fraction of information

lost in the next transmission is

reduced.

optimum degree of noise elimination.

It appears therefore that there is

some

In the above case the over-all system is improved

by quantization, at the intermediate stations, to the original levels, although in some

cases quantization to a larger number of levels may be better.

The question of noise

elimination is the main problem under study.

C. A. Desoer, R.

b.

M.

Fano

Vocoder

The possibilities of a high quality vocoder are being investigated using, initially,

the approach of tracking the harmonics of pitch frequency (1).

This and related tech-

niques are critically dependent upon an accurate knowledge of the pitch period of voiced

sounds.

Previously used methods of obtaining the pitch period appear unsatisfactory

for our purposes.

We are currently investigating the use, in this connection,

"Ianalytic function" (2)

function of time.

of speech.

of the

The analytic function of a speech wave is a complex

Its real part is the speech wave itself, and its imaginary part is the

same speech wave in which each frequency component has been shifted in phase by 90.0

To this end, a wideband (50 cps to 15, 000 cps) phase-splitter has been constructed.

When the outputs of the phase-splitter are connected to the vertical and horizontal

deflection plates, respectively, of an oscilloscope,

patterns result which constitute

a polar representation of the analytic function.

As a by-product of the above work, such polar patterns may be useful as a new form

of visible speech.

Several patterns are shown in Figs. IX-6 through IX- 11.

to the static characteristics that may be observed in these photographs,

In addition

dynamic char-

acteristics have been observed which might play an important role in the visual identification of speech sounds.

Possible uses for this method of representation are being investigated.

R. M. Lerner, R. M. Fano

References

1. R. M. Fano:

The Information Point of View in Speech Communication,

J. Acous. Soc. Am. 22, No. 6, 694-695, 1950

2.

D. Gabor:

Theory of Information, J.

Inst. Elec. Eng. 93,

-55-

Part III, 429-431,

1946

(IX.

C.

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

HUMAN COMMUNICATION SYSTEMS

Dr. L. S. Christie

Dr. R. D. Luce

F. D. Barrett

1.

J.

J.

B. Flannery

Macy, Jr.

D. G. Senft

A. G. Simmel

P. F. Thorlakson

Technical Report

Our major project during the past quarter has been the preparation of a technical

report summarizing the results and developments of the past two years.

The report

will describe the 1949-1950 experiments of Professor A. Bavelas and associates,

first explored the problem area of task-oriented groups.

who

The work of the past year,

involving a more intensive study of a restricted part of the problem area and employing

more refined experimental techniques, will also be described.

The principal experimental program (1) has been concluded.

The primary purpose

of this program was to examine learning within a task-oriented group.

light on earlier work of Leavitt and Smith.

complex data analysis required.

The results shed

Considerable time has been spent on the

This analysis will be concluded during the next quarter.

The principal development in experimental technique,

"Octopus",

is reported briefly

below and will be discussed in full in the forthcoming report.

F.

2.

D.

Barrett, L.

A Problem in Data Analysis:

S. Christie, R. D. Luce, J.

Macy, Jr.

Programming for Whirlwind I

For the analysis of the data from experiments on network patterns and group

learning (1) it is necessary to have the distributions of the number of time units, i. e.

opportunities to send a message,

required to distribute all the relevant information to

all the members of the group,

assuming equilikelihood for the use of the different

channels going out from any individual.

For many networks this problem appears sufficiently complicated mathematically to

warrant a quasi-empirical approach by means of random numbers and the use of highspeed computing machinery.

Whirlwind I was made available for this work, and a code

has been developed which is of sufficient generality to permit adjustment to different

networks by very simple modifications.

If it should become of interest to investigate

n-man groups, n 4 10, or to make some assumptions other than equilikelihood for the

use of the different channels going out from the individuals in the group, the completed

code may serve as a core around which such modifications can be constructed.

We define matrices S such that s.. = 1 or 0 according as individual j has or has not

the information originally possessed by individual i,

0 according as individual i is

and matrices T such that tij = 1 or

sending all the information at his disposal to individual

j or to someone else, letting the diagonal terms be unity in the matrices of both types.

-56-

(IX.

If we further let I be the identity matrix

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

having e.. = 1 for all i and j, we may state our problem as follows.

S

n

Ieij

e

I,

and E the universal matrix

I 18ij I

Given

S

=I

(1)

= S

n-l T n

(2)

where the product in Eq. 2 is the Boolean matrix product defined in strict analogy to the

ordinary matrix product by

S' = ST

if and only if

n

=SU

) tkj)

(ik

k=l

We want to know the distribution of N where SN = E and for all n < N, S

E.

The Whirlwind I program constructs the T-matrices as needed by means of random

digits fed from a tape into the high-speed storage in blocks of 375, guided by a set of

5 control numbers peculiar to the network under investigation.

The distribution of the

values of N < 10 will be typed out.

Testing of the program is under way.

A. G. Simmel

3.

"Octopus"

The electrical experimental device (2),

experimental groups of human subjects,

nicknamed "Octopus, " for running controlled

has been partially completed.

The individual

stations for the subjects and the central control unit have been completed and tested,

and preliminary trials using military subjects have been successfully completed.

Con-

struction of the component parts of the automatic data-recording and analyzing unit has

been finished, and final assembly and testing of this unit is nearing completion.

The

tape-recording device, using binary sequences time-multiplexed on punched magnetic

recording tape, has been completed.

Future experiments employing Octopus are in the

planning stage.

J.

4.

Macy, Jr.

Experiment on the Persistence of Organization

In conjunction with Harvey Hay, graduate student in the Department of Economics,

M. I. T.,

an experiment has been designed to detect the persistence of inappropriate

voluntary organization within a task-oriented group.

The question being asked is:

Given a group having a simple task to perform and communication by written messages

subject only to network constraints, what is the effect of shifting the group from one

-57-

(IX.

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

network to another ? It has been found in earlier experiments of a similar type that

under certain networks, groups develop an internal organization which is appropriate

to that network. Does such an informal organization persist in a new network, or does

it decay as rapidly as it is formed, when it is no longer appropriate? Further, does

the experience and consequent learning of the first network tend to affect adversely

learning in the second network?

For any group of subjects the experiment will have three phases. Five trials will

be performed on a network which we shall call P. Following these, a questionnaire

will be administered. After a break for lunch, two sets of 15 trials each will be run

on different networks, each followed by the same questionnaire as used after P. Our

interest is only in the last two phases. The network P is run in order to eliminate a

transient phase of confusion and adjustment to the apparatus.

P was chosen to be a

network within which very little organization can occur in five trials.

The questionnaire

is also used after P so that the subjects will have the same knowledge as to the content

of the questionnaire when entering phase two as when entering phase three. In addition

to P, there will be three networks used in the afternoon sessions: circle C, star S,

and diablo D. The combinations to be run are PPC, PPD, PSC, PSD, PDC, PCD.

10 groups will be run in each combination.

The apparatus to be used for this experiment is a modification of that described in

reference 1; and, in particular, includes the important feature that all communication

occurs in a quantized time scale.

This, or something equivalent to it, is necessary for

the determination of the time order of the messages sent.

The subjects to be used are enlisted Army personnel.

L. S. Christie, R. D. Luce, J. Macy, Jr.

References

1.

Quarterly Progress Report, Research Laboratory of Electronics, M. I. T. Jan. 15,

1951, pp. 79-80

2.

Quarterly Progress Report, Research Laboratory of Electronics, M. I. T. April 15,

1951, p. 52

-58-

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

(IX.

D.

REPLACEMENT OF VISUAL SENSE IN TASK OF OBSTACLE AVOIDANCE

Dr. C. M. Witcher

E. Ruiz de Luzuriaga

A small project has been set up in the Laboratory;

its object is to extend the field

of sensory replacement to the visual domain as specifically applied to the problem of

independent travel by the blind. Analysis of the performance of all obstacle avoidance

devices developed to date strongly suggests that their major failing has been a result of

inadequate means for transmission of information from device to user. In all schemes

thus far employed the information was transmitted to the user as a time series of data;

each element provided information as to the presence or absence of an obstacle in some

small specified portion of the environment.

Thus the necessary integration always had

to be done within the brain of the user.

The present aim of our project is to devise a method of transmission of information

from guidance device to user in which part of the integration process can be taken over

by the device, enabling a much needed increase of speed in the process and affording a

decrease in the mental effort which must be expended by the user.

We have started from the obstacle avoidance device developed a few years ago by

the Signal Corps, and which appears to be the most reliable and satisfactory type

available at present.

Our proposed solution to the problem of providing integrated

information consists of two modifications of this device:

1) addition of an automatic

optical scanning system, and 2) presentation of the information through the presence or

absence of projecting points, or, more precisely, round-headed pins, at various positions on a signal presentation plate.

The positions of the pins, which at any moment

project above the surface of the signal presentation plate, can be quickly surveyed by

very slight movements of the index finger of the blind user, and he can thus obtain an

almost instantaneous, if rather crude, picture of the obstacles in his immediate environment.

The positions (radial and angular) at which pins appear on the plate will

correspond roughly to the positions of the obstacles in range and azimuth, much like

the situation represented by a PPI radar presentation.

The moving pins will be actuated

by relays fed from the output of the small hearing-aid amplifier of the device.

mechanical design of the system is now fairly complete,

The

and the circuits for relay

operation have been checked experimentally.

In addition to this system for presentation of information, a tentative design for a

step-down indicator,

an element which has long been recognized as a necessity for safe

travel, has been completed.

-59-

(IX.

E.

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

COMMUNICATIONS BIOPHYSICS

Prof. W. A. Rosenblith

K. Putter

1.

Interaction of Cortical Activity and Evoked Potentials

Sizable responses to clicks are recorded from the auditory area of the cerebral

cortex of anesthetized animals. The present study proposes to investigate systematically the extent to which these evoked responses modify cortical activity and are in

turn affected by this activity.

Preliminary experimentation has been started at the

Massachusetts General Hospital.

The use of correlational techniques for purposes of

data analysis is projected.

W. A. Rosenblith with Dr. M.

2.

A. B. Brazier (Massachusetts General Hospital)

Variability of Cortical Responses to Acoustic Clicks

Responses to clicks recorded by fine wire electrodes from the auditory area of the

cortex of anesthetized animals are characterized by large variability. If a theoretical

useful quantitative description of such responses is to be given, reliable data on cortical

variability are essential.

A large number of responses have been recorded simultaneously from two locations

of a cat's auditory cortex; the rate of stimulation was varied from 2 clicks per second to

1 click every 10 seconds. The data are being analyzed by different statistical techniques

in order to determine the character of the observed variability. If the variability is nonrandom, an attempt will be made to differentiate between response-induced nonrandomness and nonrandomness due to physiological periodicities (e. g. cortical rhythms).

The experiments were carried out at the Psycho-Acoustic Laboratory, Harvard

University.

W. A. Rosenblith, K. Putter, with K. Safford (Harvard Psycho-Acoustic Laboratory)

3.

Instrumentation

A useful device for the analysis and presentation of electrophysiological data

recorded in response to discrete stimuli might have the following properties: a) it

would take "peeks" of adjustable duration at preset intervals after the occurrence of the

stimulus; b) it would quantize the evoked response at the highest level reached during

the "peeking-interval; " and c) it would present the central tendency and the variance of

the quantized data and also record the data in sequential form.

A preliminary model of such a time-gated amplitude quantizer having most of the

enumerated features is now in the design stage.

W. A. Rosenblith, K. Putter

-60-

(IX.

F.

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

ELECTRONEUROPHYSIOLOGY

J. Y. Lettvin

W. Pitts

B. Howland

With the design and building of two constant-current stimulators, a machine that

manufactures the numerous microelectrodes used in our experiments and an elaborate

control device for programming whole experiments, an electrophysiological laboratory

is being set up. The shop is now working on the design and construction of a new stereotactic instrument.

We have been applying a constant input-volley to the spinal cord, and plotting the

potential field and its changes with time at as dense a network of recording points within

the cord as is practicable.

Since the cord is narrow and a good conductor, the potential

at each point is determined by an integration over all the sources and sinks of current

in the entire cross section; and the more remote suffer only a small decrement with

distance.

These sources and sinks represent the activity of cells and fibers where they

are, for flow of current from the inside of a cell outward makes a source in the external medium in which we measure; current inward makes a sink.

The density of these

sources and sinks can be calculated by taking the Laplacian of the potential; the computing room has been doing this for us numerically from the potential maps derived from

earlier experiments.

The result is a series of maps representing the successive acti-

vity of different groups of cells or fibers.

From these maps we hope to find out how the

groups of cells combine to produce the complicated structure of the spinal reflex, and

how the transmission of information to them along pathways descending from the brain

so modifies the structure as to control movement.

To this end we plan first to complete

our analysis of the sequence of maps of sources and sinks produced by various inputs to

the isolated cord,

then to note the differences when certain of the most important

descending systems are stimulated concurrently.

Somewhat aside from this, we expect

these maps to contribute crucial evidence for or against our earlier theory of inhibition

at the synapse.

// We plan to apply the same methods, combined with various forms of statistical analysis, to a study of some of the higher sensory systems, such as the visual cortex and

lateral geniculate, from the point of view of communication theory.

To record the

potentials from one or a few points on the surface of the cortex, as has been usually

done, does not, in our opinion, furnish suitable material for such an analysis; for we

This section has been supported in part by the Department of the Navy, Office of Naval

Research, under Contract No. N5 ori-07868. Authority: NR 113-004/9-6-51, Biological Sciences Division.

-61-

(IX.

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

cannot ordinarily discover which of the numerous groups of cells and fibers, distinct in

function and connections, are responsible for the potentials recorded. But the two

methods: that of measuring potential histories at enough points to compute sources and

sinks, localizing the generators of the potentials; and the statistical methods of communication theory, should provide more information about the system, and better means

of analyzing it.

-62-

(IX.

G.

PARALLEL

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

CHAIN AMPLIFIER

The behavior of the high frequency amplifier chain of a parallel chain amplifier

has been reported in the Quarterly Progress Report, October 15,

An average

1951.

gain of about 5 db per stage was obtained over a band from 130 to 260 Mc/sec

using 6AK5's with double-tuned interstages.

The results are mentioned here only

An input circuit for this chain has been tried.

as they give an idea of the problem of network complexity when dealing with small shunt

capacitances.

It will be shown that the use of this input circuit should have considerably

Instead it was found that the gain was slightly reduced.

improved the gain of the chain.

The poor results are probably due to stray capacitances disturbing the network structure.

The input capacitance of the first stage is

terminated 50-ohm cable, which provides a 25-ohm source.

connected directly to the grid as shown in Fig. IX-12.

in Fig. IX-13,

where the source is

R = 25 ohms and C 2 = 8

pif,

The input is

about 8 p.aif.

fed from a

Originally, the cable was

The input circuit tried is shown

represented by its Thevenin equivalent.

and the products LIC

1

Here

and L2C 2 are equated to make this

circuit the bandpass equivalent of a simple series LC circuit.

If R is temporarily assumed zero, the poles of the transfer ratio, E 2 /E

occur on the jw axis, say at wI and w2 .

1,

will

Then, if we solve for the element values we

find

1

21

C

1

= C

12

2

(3)

1lW2

Returning to the lossy case, R * 0, we may conveniently express the transfer ratio

in terms of the critical frequencies of the lossless case, w1 and w

2

E2

1

=4

+ RC 2(o

2

-

1

Z 3

X + (2

(2

2

,1 2 2

2

+ RC 2 W12

1)

and also R and C 2

,

)

2

1

1+X

1

.

(4)

We may now quickly evaluate the contribution of the input network over the band for a

simple but representative case.

-63-

6AK5

50- OHM CABLE

Fig. IX-12

Fig. IX-13

Direct connected input.

Input circuit.

-

0X

*

-------.. .

L ..

jw X-PLANE

X

INPUT CIRCUIT

OF FIG. I- 13

WITHOUT INPUT

CIRCUIT (SEE FIG.I-

a,

-

130

Fig. IX-14

/

260

FREOUENCY IN Mc/sec

Fig. IX-15

Assignment of poles. The extreme

pair is realized by the input network;

other pairs are realized by interstages.

Transfer function of input circuit.

.T

T.

Fig. IX-16

An interstage used in the

low frequency chain.

-64-

12)

(IX.

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

1) 2 .

First we notice that the multiplying factor of the transfer ratio is (W -

To aid in selecting two poles from the whole array of poles of the over-all transfer

function, we also consider the multiplying factors of the interstage networks used in

this chain.

These multiplying factors are equal to ( b

-

wo)/2C where the w's refer to

the critical frequencies of a particular interstage and C is the shunt capacitance

imposed at each terminal pair.

We maximize the over-all multiplying factor, which is

just the product of the individual multiplying factors, by pairing the poles as shown in

Fig. IX-14.

This maximization gives the greatest spread for the poles of the input

network and equal spread for the poles of the interstages.

turns out to be about 5 p.Lff.

For this arrangement C 1

For expediency, let us set wl and w2 equal to the upper and lower edges of our band

(corresponding to 130 and 260 Mc/sec).

edges is,

from Eq. 4, equal to 1/[RC 2(

The magnitude of the transfer ratio at the band

2

- w1)

= 6. 1 (ratio) or 15. 7 db.

the geometrical band center, this ratio is identically one or zero db.

Similarly, at

In Fig. IX-15

these values are used to sketch the approximate transfer ratio over the band.

transfer ratio of Fig. IX-12 is also sketched for comparison.

The

(Of course, with the

addition of the input network, the interstages are appropriately realigned. ) Thus we

see that the input network should result in an over-all improvement of gain.

The low frequency chain has been built, but the alignment has not been completed.

After some delay, a setup was obtained to measure the gain over this band

(0-130 Mc/sec).

Also, a generator to sweep the entire band (0-260 Mc/sec) for align-

ment purposes has been built, using a thermally-tuned klystron.

After the gain measuring equipment was set up and a calibration run taken, a preliminary run was made on the gain.

120 Mc/sec and 130 Mc/sec.

This run showed serious attenuation between

The trouble was traced to a self-resonance of series

coils in two circuits of the type shown in Fig. IX-16.

Although some care had been

taken to keep the distributed capacitance of these coils small, they were found to resonate in the affected region, producing zeros there.

The coils are being rewound, and

it is expected that the new coils will remedy this trouble.

R. K. Bennett

H.

A METHOD OF WIENER IN A NONLINEAR CIRCUIT

Technical Report No. 217 has been prepared and has been scheduled for publication.

S. Ikehara

-65-

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

(IX.

I.

TRANSIENT PROBLEMS

Prof. E. A. Guillemin

Dr. M. V. Cerrillo

F. Reza

1.

Network Synthesis for Prescribed Transient Response

A given transient time function f(t) is to be the unit impulse response of a finite

passive lumped-parameter

network.

The problem is to find the pertinent system

function h(s) of this network.

If,

for the moment, one were to consider a periodic time function f(t), the desired

system function could be found at once from a Fourier series representation for f(t);

and the requirement that the system function be rational could be met through being

content with the approximation to f(t) afforded by a partial sum.

A study of the nature

of this approximation could be dealt with in the time domain according to familiar

techniques; and since no further approximations in the frequency domain were called

for, the ultimate response would be assured of having the approximation properties of

the partial sum.

One way of dealing with a given transient function f(t) of finite duration is to consider its periodic repetition in several ways such that an appropriate combination of

the resulting periodic functions cancels everywhere except over the first period.

A

simple pattern accomplishing this end is described in the following.

Suppose a desired f(t) is the transient pulse shown in Fig. IX-17.

We consider the

two periodic repetitions of this function as shown in Fig. IX- 18 and observe that the

corresponding transforms hl(s) and h 2 (s) are readily constructible from the appropriate

Fourier series for fl(t) and f 2 (t).

If we could synthesize a pair of two-terminal net-

works N 1 and N 2 having the driving-point functions hl(s) and h 2 (s), it is clear that their

unit impulse responses would be fl(t) and f 2 (t) respectively.

Or we can say that if we

were to apply an excitation fl(t) to N 1 or an excitation f 2 (t) to N 2 , the response in each

case would be a unit impulse.

If we now observe that

and

f(t) = f2(t)

t -

)

(2)

we can conclude that if we apply an excitation f(t) to N 1 the response is a unit impulse

at t = 0 followed by a negative unit impulse at t = T/2; while if we apply an excitation f(t) to N2 the response is

a unit impulse at t = 0 followed by another at t = T/2.

-66-

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

(IX.

Therefore,

f(t) applied to N 1 and N 2 in series produces simply an impulse at t = 0,

It remains to fill in the details

or the latter produces f(t), which is what we wanted.

with appropriate mathematical symbols.

We begin by considering the periodic function f p(t) shown in Fig. IX- 19,

Writing the Fourier series

of a repetition of f(t) at half-period intervals.

f (t) = E

consisting

akejkt

k=- oo

we have for its transform

p(s)

q( "

ak

h (s)

s - jkw

hp(S)

k=-oo

(4)

The transforms hl(s) and h 2 (s) are readily constructible from h (s).

p

oo

ak(1 + e-Jk)

hl(s) = hp (s)

s - jkw

(5)

and

00

I-.a

h 2 (s) = h (s) (1

- e

-

a_(1 - e

- jkw

K'

ST/)

-00

Noting that the factor (1 + e

- jk

w) equals 2 for k even and zero for k odd, while the

factor (1 - e - jk w ) equals 2 for k odd and zero for k even, we have more simply

ak

h l (s) = 2

s-jk

k=0+(2,4, ..

P 1(s)

ql(s)

(7)

)

and

oo

ak

-jk

h 2 (s) = 2

P 2 (s)

S

(8)

k=+(1, 3 ... .)

That is to say, hl(s) is twice the sum of the

even order terms in hp(s), given by Eq. 4,

while h 2 (s) is twice the sum of the odd order

terms.

As long as the sums in the expressions for

hp(s), hi(s) and h 2 (s) are regarded as having

Fig. IX-17

The desired transient time function.

an infinite number of terms, these transforms

are, of course, not rational and the polynomials

-67-

Fig. IX-18

The auxiliary periodic repetitions of f(t).

i fp(t)

II

-

r\

%

#

r/2

T

T/2

-

./2

Fig. IX-19

The basic periodic repetition of f(t) from

which the auxiliary functions of Fig. IX-18

are derived.

fp*(t)

/'""

O

rj

-

I

I

1

f*(t-r/2)+A f(t)

af(t)

III

,.~~~-"1.

A

I

f

I

v.

.

I

-

I

Fig. IX-20

Approximation to the periodic function of

Fig. IX-19 afforded by a partial sum of its

Fourier series, and the imperfectly delayed

version of this function.

-68-

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

(IX.

p(s), q(s), p 1 (s),

Since we anticipate replacing

q 1(s), pZ(s) and q 2 (s) are not finite.

these expressions by their partial sums, it is appropriate even at this stage to think of

the polynomials as though they were finite. They obviously have real coefficients even

though the Fourier coefficients ak (which are residues of the h functions in their j axis

poles) are complex.

If we think of networks N 1 and N 2 as having the driving-point functions hl(s) and

h 2 (s), then a unit impulse u (t) applied to N 1 produces fl(t) and if applied to N 2 , it

produces f 2 (t). If we now interchange the roles of excitation and response, and say that

fl(t) applied to N 1 or f 2 (t) applied to N 2 produces u (t), then the system functions for

these networks are the reciprocals 1/hl(s) and 1/h 2 (s). Noting Eqs. 1 and 2 we may

then state that f(t) applied to N 1 having the system function 1/hl(s) produces the

response

(9)

uo(t) - u 0 (t -)

while f(t) applied to N2 having the system function 1/h

(1/hl) + (1/h

(s) produces the response

).

u (t) + u0 (t Wherefore,

2

(10)

f(t) applied to N 1 and N 2 in series with the resultant system function

2

) produces the response 2u o (t); or if we again interchange the roles of

excitation and response and consider the series combination of N

1

and N2 as having the

system function

1

1

2

then its unit impulse response becomes (1/2) f(t), as may readily be verified through

substitution of Eqs. 5 and 6 into Eq. 11, which yields

h(s) =

1

h p(s) (1 - e-s

S

P(s) " P 2 (s)

2p(s)

"

(12)

Since the time-domain equivalent of this equation reads

f(t) =

(f

(t)

- f(t-T))

(13)

the above statement is seen to be true.

Neglecting second-order effects, it is easy to show that when one replaces the above

infinite series by their partial sums, the resulting transient response is as good an

approximation to f(t) as the partial sum of the Fourier series given in Eq. 3 is to f p(t)

over any one of its periods.

Thus, if we indicate any approximate function through

attaching an asterisk to the corresponding exact function, we may write

-69-

(IX.

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

n

f (t) = )

akeJt

(14)

k=-n

n

h(s)

hp (s)

a

=k

(15)

s - jkw

k=-n

and

-jk*

n

h (s) e-ST/2*

p

ake

k=-n

(16)

s - jko

(16)

where n is a finite integer.

Figure IX-20 shows how the approximation to f p(t) given by the partial sum (Eq. 14)

might look, and correspondingly how the inverse transform of the frequency function

(Eq. 16) will appear. It is important to note that this time function may be regarded

as an imperfect version of f (t) delayed by a half period. Thus, the perfect version of

f (t) delayed by a half period differs from the function shown in the bottom half of

Fig. IX-20 in that it is exactly zero throughout the first half period. The imperfect

version, by contrast, has the same nonzero ripply variations here that it has in any of

the corresponding subsequent half-period intervals. Observe, however, that the imperfect and perfect versions are exactly alike everywhere except during the first half period

where they differ by the residual ripple which in Fig. IX-20 is denoted by Af(t). That

is to say, the net difference Af(t) between the imperfectly and the perfectly delayed

functions f (t) is nonzero only for the interval 0 < t < 7/2!

p

In the frequency domain we can express this result through writing

h (s) e-/

p

2

h (s)

p

e- r/2+

Ah(s)

(17)

and interpreting Ah(s) as a frequency function whose inverse transform is Af(t) and

hence is nonzero only for 0 < t < 7/2 where it amounts to a small ripple. From Eq. 17

we may now form

- s r/ 2

- s

e

e

/ 2

h(18)

+(18)

h

p

Through squaring and neglecting the term involving (Ah)

2,

we have

- ST

ST*= e --S-+ 2h

2Ah eT/

- sr/2

h

p

whereupon the pertinent relation (Eq. 12) becomes

h *(s) =

h (s) (1 - e7

*) =

p

(s) (1 - e-T) - Ahe

7 h P20

70-

(19)

- s r / 2

(20)

(IX.

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

and the corresponding time function is

f(t) =

(fp(t) - fp(t-)

-

Af(t -

(21)

.

for the

The first term in this last expression equals one-half the function f*(t)

p

*

interval 0 < t < T and is zero otherwise. The second term is f (t) for 7/2 < t < T with

P

The result (except for a factor of 1/2) equals f (t) for 0 < t < '/2,

its sign changed.

-f (t) for T/2 < t < T, and is zero otherwise.

p

The second-order effects, which have been neglected, will slightly alter the form

of f*(t) during the interval 0 < t <

T,

and will prolong the error in an asymptotically

decreasing fashion thereafter.

The method of finding a system function appropriate to a desired transient pulse of

arbitrary shape as discussed in the above paragraphs is the logical generalization of

a method used during the war for designing networks to produce rectangular radar

pulses. It took the writer approximately ten years to stumble upon this generalization.

E. A. Guillemin

2.

Basic Existence Theorems

Section 1

A New Integral Representation of Laplace Transforms

A set of new integral expressions for the representation of direct and inverse

Laplace transformations will be presented first. These integral expressions are the

1. 0

basic tool for proving a set of existence theorems for fundamental problems in the

theory of network synthesis. Several existence theorems are presented in this report.

1.1

Let

f(t) =

f 0

0

for t > 0, and such that

(1)

for t < 0

where M and c are finite positive constants.

Let c o , the abscissa of convergence,

the lowest bound of c which satisfies this inequality.

Laplace transformable.

If(t)I < Mect

be

Then, as is well known, f(t) is

Its transform F(s) is analytic in the right half of the s plane

beyond the line parallel to the w axis and at a distance c o from it.

The direct and inverse Laplace transformations are given,

integrals

-71-

respectively, by the

(IX.

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

00

f(t) e - s t dt

F(s) =

s

+ iw

0

f(t) = I

JF(s)

est ds

fT171d

where r is a line going from -ioo to ioo such that all the singularities of F(s) lie to the

left of F.

1.2

For the purpose of our representation we shall select F as a symmetric curve,

having the branches F and F'. F' is the image of F with respect to the real axis, as

shown in Fig. IX-21. An arbitrary point of the s plane will be denoted by

s =

For points on the contour

cr + iW

(3)

Ewe shall use, for convenience, the notation

S = y + iX

(4)

Finally, the analytic expression for 1 is

(y,

)= 0

(5)

A simple algebraic process shows that the second integral in (2) can be expressed

by an integral along F only,

f(t)

=1

f

F(S) eSt dS - F(S) et

Zi

dS

from which we obtain the form

f(t) =

±

eyt

U(y,k) [sin Xt dy + cos Xt dX

F-

+ V(y,k) [cos Xt dy - sin Xt dX]

(7)

in which

F(s) = U(o-,

) + iV(cr, w)

F(S) = U(y,X)+

(8)

iV(y, X)

1.3

Let us indicate by I the distance from the point P to yo along the curve T as

indicated in Fig. IX-22.

From Eq. (5) we get

-ad

dy + a

-

d X=

d

= 0

and we shall introduce the well-known relations

-72-

(9)

Fig. IX-21

The contour P

is defined by the function €(y, X) = 0.

Fig. IX-22

The contour I, the coordinate I and the direction cosines of d.

s PLANE

Fig. IX-23

The contour r.

-73-

0

(IX.

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

a

cos 0(y,X) =

dy

)2

2~

(10)

2a

sin

()D

(y, x) =

A few algebraic manipulations lead to

f(t) =

f e

IF(y, k)

sin [Xt +

(y, ) +

(y, )] dcU

(11)

in which

'

F(S) = IF(y,X) I ei(y, X)

1.4

(12)

We shall now obtain the corresponding expression for F(s).

Since

f(t) est dt

F(s) =

0

then one can multiply (7) by (e s t dt) and integrate between zero and infinity. By

reversing the order of integration (which is justified here because r is to the right of

the singularities of F(s)), and considering the integrals

X

(s-y) 2 + 2

e-st e

sin

t

(13)

s-y)

(s-y)

+x

one gets

F(s) = IfU(y,X)

[Xdy + (s-y) d

+ V(y,k

)

[(s-y) dy -

1

dk]

(s-y)

+X

(14)

By introducing the functions defined by

s - -

(s-y)

(s-y)

=

cos K(s, y, k)

+

+ x

sin K(s, y, X)

-74-

(15)

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

(IX.

one gets

F(y,X) sin

F(s) =

1.5

K(s,, y,)

(16)

d

(y)

+(y,)+

The expressions for f(t) and F(s) of a strategic contour are very useful in proving

the final forms at which we are aiming.

They also play a basic role in later theorems.

The new contour is the semi-infinite line obtained by setting y = -o = constant > c .

See Fig. IX-23.

This particular contour will be designated by 0

The corresponding integrals follow by setting dy = 0, or 0 = w/2, and dX = dl.

They

are

yt

f(t) = e

1

U(Y o

,

) cos Xt - V(Yo,

Xt

) sin

dX

o

(17)

IF(yO, X ) I cos [Xt +

= e-

(yo,k)

dX

(s -

P

) +X

(18)

=

IF(

,X)I cos [K(so,

k) + P(,)

dX

ro

1. 6

Our aim is to produce two final sets of basic integral representations.

The first

of these sets reads

f (t) =-

2 r vt..

e' U(y,

r

=2f eYtU(y,X)

7

r

) Lcos Xt dX + sin Xt dYjI

[sinXt + 0(y ,)]

Cd

(19)

F(s) =

j

Xdy + (s-y) d)

S(s-y)

=.

sin

)

U

2

+

X

K(s, y, ) 6(y, )1 U(y, k) d~i

Iwhich

both

permits f(t)

usto express

and F(s) in terms of the real part of F(s)

which permits us to express both f(t) and F(s) in terms of the real part of F(s)

-75-

(IX.

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

along the contour F.

A direct proof of (19) is rather long for this report.

Instead, we shall first furnish

a simplified (and correct) proof, valid for the particular contour F

F to F is not difficult.

o .

The passage from

0

1.7

The proof for

example,

E.

Fo

follows with ease by introducing Hilbert transforms. (See,

A. Guillemin: "'The Mathematics of Circuit Analysis, " John Wiley,

New York 1949,

for

pp. 330-349.)

Let f(z) = U(x,y) + iV(x, y), z = x + iy.

The transforms are given by

+00

U(x,y) = -f

xU(o,

Tx

d

0) x 2+ (y-n)

(20)

+00

V(x,y) = -f

(y-

) U(0,

d

- 00

To apply them to our case we set x = y - yo,

F0

+ F'.

0

y = X, and designate by

0 the contour

We obtain

U(y,X)

-

=

Y)

U(Y,

S(V -Vo)

d

+ (X-)

Fo

(21)

V(y,)

(_

= -

-YO)2

'T

- (y - y 0

(

+

(X-Tl)

10

1

2 d_)

/

where yo > c o . Substituting these expressions in (7) and inverting the order of integration (justified by the condition yo > c ) one gets

f(t)=

1

F

U(yo,1) d

f et

r0

I

U(y,X) (sin Xt dy + cos Xt dX)

(21a)

+ V 1 (Y, X) (cos Xt dy - sin Xt dk

where

U(Y,X

) =

Y - ¥o

V

(V - YO)

2

+(X-q)

(22)

V(Y,

X)

=

-

)

(V- ( ,)2 (X+ (×-hi

n

-76-

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

(IX.

respectively,

One recognizes immediately that expressions (22) are,

the real and

imaginary parts of the function

(23)

F 1(S) = s - (y

0 + in)

=

The corresponding time function, say fl(t), is

S

t

0

for t < 0

(24)

fl(t) =

e+(o +i)t

Now,

reveals immediately that the bracket parenthesis of (21a) is

expression (7)

Consequently, Eq. (21a) becomes

exactly the function fl(t).

U(y 0 ,

)

for t > 0

e

(y +iq)t

U(y , 0 )

dq = e T

cosi

t +

i sin

t]

d'

for t >, 0

.

L

(25)

f(t) =

for t < 0

Finally, recalling that U(y 0 , 1) (in Laplace transforms) is necessarily an even function,

one gets, by changing 9 to X

U(y

S2e

,

k) cosX t d

for t > 0

r

(26)

f(t) =

fort <0

0

where yo > c .

By the direct Laplace transformation of (26) we get

F(s) =

2(s -Yo)

IT

U(o, X) dX

for yo > co

(s -

-77-

o) +X

(27)

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

(IX.

Therefore,

1.8

expressions (26) and (27) show the veracity of (19),

at least for

=

0o

Expressions (26) and (27) produce both f(t) and F(s) in terms of a generic function

U(Y0o ,

) for F = o .

These expressions can be solved for U(a, o).

From the first integral in (2) one gets

F(s) = U(cr,

f(t) e - 3 t (cos ot - i sin ot) dt

) + iV(a,wo)=

(28)

from which

U(cr, w) =

Je

-

t

cos wt f(t) dt

0

Hence

(28a)

0o

U(Yo, X) = e

f(t) cos Xt dt

o

0

which inverts (26).

The inversion of (27) is obviously given by

= Real (F(s))

U(o-,o)

U(o ,

) = Real (F(s)s

=S

for S = 'o

+

ii

For convenience we shall put these integral representations together for

will be very helpful in a subsequent discussion.

f(t) =

2e

(29)

I

= po .

0

They

ytt

U(y ,X) cos Xt dX

o

F(s) =

2(s - yo)

U(y0 ,X) dX

(s - y

U( 0 ,kX) = e

o

U(o, X) = Real

)2

+ X2

(30)

'f

f(t) cos Xt dt

F(s)4s = S

-78-

for S = -y + iX

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

(IX.

where yo > c 0

The reader may note the apparent simplicity of these expressions and

the interchangeability of the functions U(-

r=r

o

f(t) e

, X) and (

t) along a contour

o

1.9 We must now prove the correctness of (19) for any F contour (for which all the

singularities of F(s) lie to the left of F). A simple (heuristic) reasoning renders a

lucid proof. It is based on the following well-known facts of the Laplace transforms.

Let f(t) have F(s) = U(cr, w) + iV(or, o) as Laplace transforms.

Now, let us construct a new function

G(s) = U(a-, o) - iV(o-, o)

Then

for t> 0

0

(31)

for

L-1(G(s)) = g(t)

for t < 0

f(t)

(The proof follows by setting

f(t) = f 2 (t) + fl(t)

0 = f 2 (t) - f (t)

1

where f 2 (t) is an even function of (t), and f 1 (t) is an odd function of t.)

To prove our expression (19), we use (7) and set

g(t) =

r

sin Xt dy + cos Xt d] - V(y,

eYt (U(y,)

) [cos Xt dy - sin Xt dXk

(32)

Therefore, as a consequence of (31) for t > 0,

f(t)+ g(t) = f(t)

f

et

U(y,

) [sint

dy + cos Xt dX}

fort> 0

(33)

By direct integration of (33) one gets

F(s) = 2 f

F(s)

dy + (s-y) dk}

II(s-y)

U(

X)

+ X

(34)

Therefore, the representation (19) is correct for every contour F as prescribed before.

Similarly, as in Eq. (30), Eqs. (33) and (34) can be solved for U(y,X). Take (28)

and set s = S.

Then

-79-

(IX.

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

Yt

f(t) e

U(y, X) =

(cos Xt) dt

0

(35)

X(y,

) =0

1. 10

The integral representations developed in the previous pages have been found by

using the two basic assumptions:

c t

f(t)

(a)

(b)

4 Me o

The contour

for every value of (t)

P

must always stay to the right of every singularity of F(s).

Under these conditions all of the integrals above exist in a Riemann sense.

Our analysis

breaks down if we allow the contour of integration to go through one or several singularities of F(s), keeping the rest of the singularities to the left of F.

for

=

0 this situation arises when yo = c .

integral fails to exist.

impulse at t = t o

for t = t

.

.

For example,

Under this assumption the Riemann

Stipulation (a) excludes a very important time function:

Clearly condition (a) does not hold for every value of t,

However,

the unit

in particular

U(y,X) exists in this case since

U(y, X) I

dt < j

ff(t) e

0

f(t)

(36)

dt = 1

0

A set of important existence theorems in network synthesis can be obtained with

' to run through several or all singularities of F(s),

always keeping the remaining singularites to the left of r.

It is also important to

ease when we allow the contour

admit time functions formed by a time distribution of impulses whose total area is finite.

This new situation can be handled by the introduction of a new Stieltjes integral

representation which contains, as particular cases, the Riemann representations derived

above.

For the purpose of this report, it is enough to produce the Stieltjes integral

representation for r =

Fo valid now for yo > co (abscissa of convergence).

progress reports we shall consider the general case

.)

(In future

The briefness of a progress

report forces the assumption that the reader is acquainted with at least a few elementary properties of Stieltjes integrals.

1. 11

We will introduce directly,

without further elaboration,

Stieltjes integral representation for

P=

I

o

, -y >Co .

the corresponding

Let us introduce the following

functions, which we will assume exist and are of bounded variation;

The reader may immediately produce the representation for any P with relative ease,

particularly when r possesses continuous first derivatives for all values of 1.

-80-

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

(IX.

(yo,

along F

U(yo, 1 1 ) d

=

)

(37)

t

"(y , t) =

(38)

e

f()

0

and an alternate function

t

T(t) =

f()

(39)

d.

The definition of "bounded variation" implies the existence of the integral inequalities

IU(y,X)

If(t) e

I

-y t

dX <

(40)

oc

dt <

(41)

00

and alternatively

If(t)l dt < 00

(42)

0

Under these stipulations, the corresponding Stieltjes integral representations (which

contain (30) as a particular case) exist:

f(t) = 2e

yt

cos Xt dp(Yo,X)

(43)

Fw)=2(

F(s) =

2(s - yo)

1T

d((y , X)

(s- yo

U(y0 , ) = j cos Xt

0

and alternatively

-81-

)

+X

dT(yo, t

)

(44)

(45)

(IX.

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

00

k) =

U(Yo,

(46)

e Yot cos Xt dT(t)

0

if (42) holds.

With these integrals, as will be shown later, we can set yo > co.

The equality sign

is unacceptable in the Riemann integral representation.

For yo > co the representations above coincide with (30). Take (43) and (44), which

depend on (Yo0 , X). A well-known theorem of the Laplace transform of a time function

c t

f(t), If(t)I 4 Me o , states that F(s) is analytic for every point s of the right half-plane

defined by the line s = c + iw. The selected contour lies completely in points of analyticity of F(s), since yo > c .

The corresponding continuity and finiteness of U(y

allow us to differentiate the integral (37) with respect to X. Hence

d4(yo,X) = U(yo,X) dX

o ,r)

(47)

which justifies the assertion.

Examples of the application of these integrals will be found later.

1. 12

Equations (43) to (46), particularly (44), will be written in a canonical form which

is basic in the existence theorem of transfer functions.

we will refer directly to the integrals (43) and (44).

For briefness in presentation

The corresponding extension to

(45) and (46) is obvious.

From (37) and (40)

IYo ,

< i IU(Y, X)) dX < 00

(48)

0

indicating that

(Yo, X) is a function of "bounded variation" in the interval (0, oo).

The following theorem (well-known) will be used.

Theorem (1-1.12).

(a, b).

Let

c(X)

be a real function of "bounded variation" in the interval

Then, there exist two functions c(+)(X) and

()()

which in (a, b) are:

i) non-

negative; ii) nondecreasing; iii) bounded, and vanishing at X = a; iv) discontinuous at

the same points as p(X),

such that

p(X) -

(a)

(X) -

(_()(X)1

(49)

Va(X)

where Va(k) is the variation of

=(+)()

+ ()()

(X) in the interval (a,

Although the proof is simple, we omit it here.

functions Va(X)

4(+)(),

(_)().

The function Va(X) is given by

,

-82-

k).

Our concern is to construct the

(IX.

Va(Yo,

) 1dT

0

IU(-o,

) =

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

(+)(Yo, ) -= U(1)(Yo,

(50)

) di

0

,( )(yo,

X)=

where

U(1)(Yo, K) =

IU(Yo, X)

for U(Yo ,X) > 0

0

for U(Yo ,X)< 0

0

for U(yo,

(51)

U ()(o,

)=

)

> 0

(YX)

)l for U(Y o ,X) <

=I|U(vo,

0

Figure IX-24 provides a simple graphical illustration of the process of the extraction

of U( 1 )(Yo, X) and U( 2 )(Yo, k) from U(y 0 , X). Figure IX-25 produces the corresponding

graphs of Va(X),

(+)(), (_)().

The above theorem and the conditions of boundedness imposed on the functions

(43) to (46) as the difference

(y', X), T(y o , X), T(y o , X) justify the writing of integrals

always real, non-negative,

T

(_)are

T +),

(_), T(+), T(_),

of integrals, where (+),

nondecreasing, etc., functions.

Hence

os Xt

f(t) = f( 1)(t) - f( 2 )(t) =

d()(y,

)

cos Xt d(_)(

-e

F(s) = F(1)(s)-

F(2)(s)

d (+ )(Y0 ,X)

2(s - y )

I

(s - yo)

2

2(s-

z

-y

)

I

dP(

(s -

T+

)(Y

(53)

o ) + X(53)

1o

ro

U(,

(52)

To

ro

=

,

0 X)

X)= U( 1 )(Yo,X) - U( 2 )(Y0 , X)= f cos Xt

dT

)(,

t) -

Scos

0

0

or alternatively

-83-

t

dTr)(y0 ,t)

(54)

(IX.

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

U(o,

k)

) = U( 1 )(Yo,X) - U( 2 )(y,

o-yY t

e

cos Xt dT(+)(t) -

=

0

e

-y t

cos Xt dT _ (t)

0

(55)

which are the forms we wanted to introduce. The following properties are important.

It can be noted that when U(y o , X) along 'o , (Yo > C ),is either a non-negative definite

or a nonpositive definite function of X, then only the (1) system or the (2) system,

respectively,

exists.

Several other theorems are omitted for brevity.

1.13

A series of basic existence theorems on transfer functions will be deduced, in

section 2, from the integral representation given above. We are going to show that the

functions Fl(s) and FZ(s) are positive real, (p, r) when c , the abscissa of convergence,

is equal to or less than zero.

In the light of the result given above,

F(s) can immediately be recognized as a

Now, all real, single-valued, bounded functions of time

transfer function if co < 0.

have an abscissa of convergence in the Laplace transform c o which is equal to or

less than zero. Besides, the Laplace transform is a transfer function which can

degenerate into a single (p, r) function if U(O, X) >, 0 for every point in the interval

(0o< X< oo).

The transfer character of F(s) immediately suggests the existence of a certain

discrete network which realizes this transfer function. We will show that for Co

0

0

we can find a four-terminal passive network which realizes this F(s). For c > 0

we enter the realm of active networks. Section 2 presents a series of theorems concerning the situation indicated in this subsection.

U(yr,X)

0

v a (X)

I

x

i~--CD

I

I

I

I

I

UI

L

K

-

N

--

J

I

I

I

I

~-*-

I

U(2 0)( 0 ,X

t0

H-

M

I

I

Fig. IX-24

The functions U(1)(Yo, X), U( 2 )(Yo 0 ,).

I

I

I

I

Fig. IX-25

The functions Va(k),

)()

-84-

I

I

I

,

(_)().

(IX.

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

A final form of integral representation is given in this subsection. We have

assumed that the contour F runs to the right of all the singularities of F(s). The new

representation is valid when the contour P leaves some singularities to the right and

1. 14

This representation is important because it reveals the character

of the singularities of F(s). In fact, it shows that F(s) has a meromorphic behavior in

.

the half-plane defined to the right of

others to the left.

The following form is given with regard to r

o

, but y > co.

Let f(t) be bounded as in the previous theorems, then

Theorem (1-1.14).

(s-

exp

F(s) =

+

(s -y)

o)

ro

(X) is a function of "bounded variation. " 1T 1 and Tr2 are Blaschke products.

x

0

Note: The Blaschke products are constructed in our case as follows. Let s' , s'

where

be respectively the poles and zeros of F(s) to the right of

I

Z'

S'

Z

s-

o

. Then

cos pP + s'

s'I

r

I

TT-

+

s ' l

'

c os

+ s,

FT

1-i.

S

2

-

v,

I'

+ s's'I os P + s'

IJ

s ' I cos

x

P

+ s '2

s' = (s - y0 )

Section 2

On Transfer and Impedance (or Admittance) Functions

2.0

Two-terminal impedances, or admittances, of a discrete or a continuous passive

network belong to the class of positive real, (p, r) functions.

In general, positive (p) and positive real (p, r) are defined as follows:

Let Z ((s),

s = a- + io,

be

(a)

single-valued

(b)

analytic for all points a- > 0

(c)

such that, if we write Z = U(o-, w) + iV(C-,

0), then U(-,w) > 0 for - > 0.

If these conditions are satisfied, then Z (p(s) is called a positive (p) function (of the

right half-plane).

If,

in addition,

Zp (s) also satisfies the fourth condition

-85-

(IX.

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

(d) that Z(p)(s) is pure real for s real

then Z p)(s) is called a "positive real function, " (p,r) (of the right half-plane).

For convenience we will introduce the notation Z(s), composed of Y and Z, for (p,r)

functions.

We assume that the reader is acquainted with the following theorem (HerglotzCauer).

Theorem (1-2.0).

The necessary and sufficient condition for a function H(s) to be

analytic and have a positive real part for a-> 0 (s = a- + iw) and to be real for s real,

(in other words, to be (p, r)), is that it can be expressed by the Stieltjes integral

o00

H(s) = (Z(s)) =

+ sC

(56)

where p(X) is a nondecreasing, non-negative, real function of "bounded variation," and

C is a constant (equal to lim sZ(s)).

S-0o0

2. 1 With this theorem as a basis, we can produce the following theorems.

Theorem (1-2. 1).

If co 4 0, then the functions F( 1 )(s) and F( 2 )(s) are both (p,r).

For

this reason we will use the suggestive notation F(1 = Z(l and F(2

)

),

) = Z(2)

Theorem (2-2. 1).

is zero for t < 0.

Let f(t) be a real, single-valued, bounded function of time, which

f(t) may possess a denumerable set of isolated points of simple dis-

continuity and a denumerable set of isolated points where f(t) shows an impulse of finite

area, such that the sum of the areas is finite; then the associated functions F(1)(s) and

F(2 )(s) are both (p,r) functions.

It is enough to show that co

.< 0.

For if f(t) is bounded and has a bound M almost

everywhere then the condition of Eq. (1),

If(t)I < Mect, is satisfied with c = 0.

The

impulses are taken care of because they satisfy (42).

2.2

Now, let us produce two basic theorems.

If, by extension of the ideas in the theory of networks,

we define a "transfer

function" as the difference of two (p, r) functions (in section 3 there is a justification of

this extension), then we can produce the fundamental theorems of existence of transfer

functions.

Theorem (1-2.2).

The necessary and sufficient condition for a function H(s) to be a

transfer function, is that it can be represented by the Stieltjes integral, (57),

alternate forms (58), (59):

-86-

or its

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

(IX.

sin K(s, y,X) + 0(y,X)] d(I)

F(s) =

2

F(s) =- T (s -

<

0O s

for every continuous contour

0)

j

F

d(y , X)

(s- yo)

(57)

(58)

+

+X

+

F which shall be made to coincide with the upper

imaginary axis (as in (59)), where 4(I), 4(y

0

, X) and p(O,X),

respectively, are functions

of "bounded variation" along F.

The results are independent of f.

The condition c o

0 implies that F can coincide

<

wholly with the positive imaginary axis.

Theorem (2-2.2).

Then, its Laplace trans-

Let f(t) be as defined in theorem (2-2.1).

form is necessarily a transfer function.

Theorem (2-2.3).

Let F(s) be a general transfer function as defined above.

Then its

inverse Laplace transform is necessarily a function f(t) as defined in theorem (2-2.1).

The fundamental character of theorems (2-2.2) and (2-2.3) in regard to network

theory is quite obvious for they define the open field of network synthesis possibilities.

A group of related theorems was omitted

The network aspect is discussed in section 3.

for lack of space.

2.4

For convenience we shall illustrate with simple examples the application of the

theorems given above.

Example 1.

The function e-s is a transfer function which represents the unit delay.

Its inverse Laplace transform is

a unit impulse delayed one unit of time.

From e

theorem (1-2.2) and use, for example, (58).

-

U(y , X) = e

Direct theorem.

integral.

V0

o

- s

one gets

os X

can be taken as a Riemann

Let us consider yo > c , so that (58)

Then

Consider

00

2(s - Y0 ) -yo

F(s)

cos X dX

e

-

0

(s-g

2

)

+

+

2

The value of the integral in (60) can be obtained from the well-known result

-87-

(60)

(

(IX.

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

W

cos x

-a

a +x

Hence

2(sF(s) =

Example 2.

a > 0, b > 0.

yo)

Direct theorem.

-Yo

-_0

e

S

(

2(S - Ylo

e

-(s -

o)

-s

=e

Let us consider the transfer function F(s) = (s-a)/(s+b),

The abscissa of convergence is s = -b.

Then, for simplicity, we can set

o = 0 (Riemann integral).

By direct computation

2

2

L

X2 - ab

X - ab

1

L

U(0, X)=2

'

2

2+2

2

22

2X + b s +X 2X 2 + b

X2 + b

L

2

2

X2 + s

where

b+ a

L

s

2

s

2

-b

2

- ab

s

b

2

By direct substitution in (60) and using the well-known integral

+ x2 =

a

oo

F(s)

-j

0

Example 3.

22

+b

s

=

22

+X

-

7

Illustrations of the inverse theorem-Stieltjes integral.

Now we can

arbitrarily choose U(y 0 , k), except that it must be of "bounded variation." For simplicity set yo = 0 and choose U(0,X) as in Fig. IX-26a. Here, the Riemann integral evidently fails to exist. The Stieltjes integral exists and for the particular selection of

U(0,

k) it reduces to a sum of finite terms.

oo

F(s)= 2s

S

d(k)

2

2

0 s+

s

Ia

z

l

+x

= z(1)(s)-

a3

2 +2

1

s

2 +2

+1X s

a2

a4

+X2

2

a5

2

s

2

Z( 2 )(s)

from which the (p,r) character of Z( 1 )(s) , Z( 2 )(s) and the transfer character of F(s) are

evident.

-88-

n II

,

MIma

CJ

A2

0

O

1

I

X3

XI

+ C

+IN

4c.I

a,

dH

X4

Sn

(a)

(b)

X4 X5

A

(C)

(d)

Fig. IX-26

(a) The selected function U(O,

); (b)

;=

U(O,

) dk;

0

(c) the function

(

); (d) the function

-89-

(_)(k).

(IX.

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

Example 4.

Here, we will illustrate the use of integral (43) in computing the corresponding time response associated with U(0, X) as defined in example 3.

Setting y

= 0 in (43), the Stieltjes integral reduces to a finite sum of terms.

immediately gets

f(t) =a

One

cos Xt - a 2 cos X2t + a 3 cos X3t + a 4 cos X4t - a 5 cos X t

2.5

We close section 2 by pointing out three basic features of our integral representation:

(1) The functions f(t) and F(s) are uniquely determined in terms of the function

U(y,k) along an arbitrary contour F .

(2)

The function U(y,k) and the contour

restrictions already given.

(3)

F can be arbitrarily chosen, except for the

Then, for any selection, the above integrals allow

us to generate a transfer F(s) and its inverse Laplace transform.

Conversely, given f(t), or F(s) we can find the corresponding value of U(o-, W)

along a prescribed contour F .

Section 3

The Electrical Passive Network Associated with the General Transfer Function F(s)

The functions F(s) generated by an arbitrary selection of U(y,X) and F are not

necessarily rational functions. Therefore, the existence of the electrical networks

3.0

which synthesize them is not evident.

The purpose of this section 3 is to show the

existence and construction of such networks.

Theorem (1-3.0).

Discrete networks.

The main theorem of this section is:

Let f(t) be a real, single-valued, bounded function

of time, which is zero for t < 0. f(t) may possess denumerable sets of points of isolated

simple discontinuities, as well as a denumerable set of points at which f(t) possesses

impulses of finite area whose sum is of "bounded variation. "* Then there exists a

passive linear, finite network, having finite element values such that its transfer

function F (s

approaches F(s) uniformly as n -o for every point s, C- > 0. Let f (t)

be the time response corresponding to F (s). Then, f (t) is zero for t < 0 and any n,

and fn(t) tends to f(t) as n-oo at almost every point 0

t< oo. (The exceptional points

)

are the sets of discontinuity and the impulses of f(t).)

The proof consists in finding a sequence of functions Un(X,y) such that Un(Xk,) -U(X,y),

as n oo, and each Un(X,y) possesses an Fn(s) which is necessarily a rational transfer

function. Instead of formal proof we use a simple and illuminating heuristic approach.

The theorem is true for a more general class of functions f(t).

select f(t) as defined by theorem (1-3.0).

-90-

For simplicity, we

COMMUNICATION RESEARCH)

(IX.

Theorem (1-3.0) has an alternative form associated with "continuous" networks.

3.1

Heuristically, we can see with ease that theorem (1-3.0) (and its alternative form

The conditions imposed on f(t) imply that co < 0.

for continuous networks) is correct.

(if the singularities stay on or to

Since the results of our integral are independent of P

the left of

For simplicity, let us start by taking an arbi-

F), then one can use -o = 0.

From U(0, X) we