JUN 2009 3 0 LIBRARIES

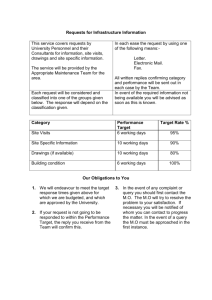

advertisement