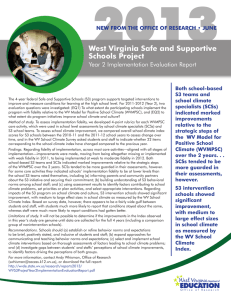

West Virginia Safe and Supportive (S3) Schools Project

advertisement