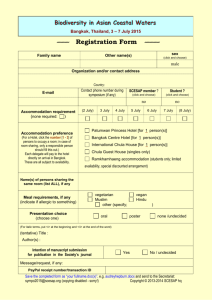

Open to the Public!

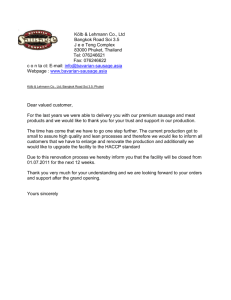

advertisement