Document 11080423

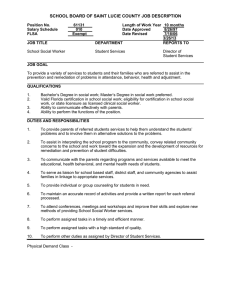

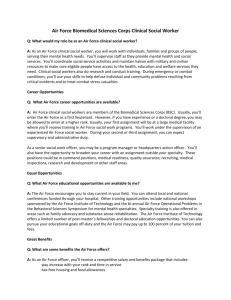

advertisement